- In short: The proportion of rentals that cost less than 25 per cent of household income is at the lowest level in records going back to 2008.

- Almost no rental properties are considered affordable for the lowest-income 30 per cent of households.

- What’s next? PropTrack senior economist Angus Moore says building more well-located housing is the key longer-term solution to lower rents relative to incomes.

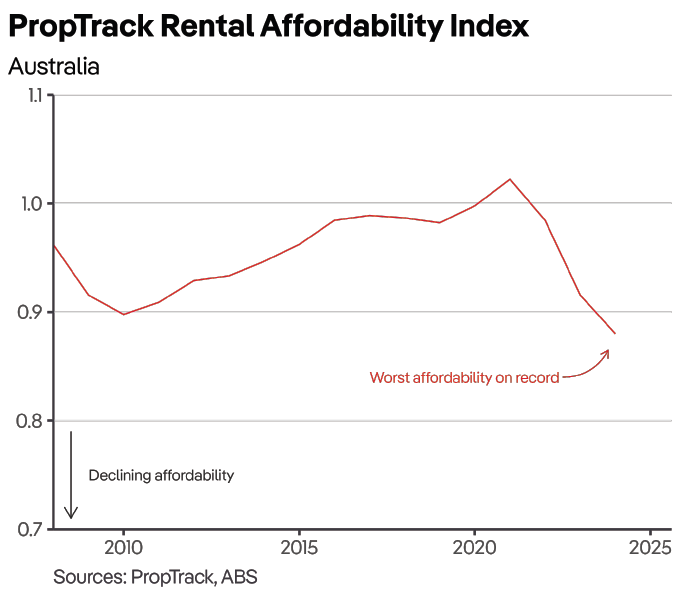

Rental affordability is at its lowest level in at least 17 years, having swung dramatically from record levels of affordability during the early stages of the COVID pandemic.

The analysis from PropTrack — a real estate data firm owned by property advertising platform REA Group — goes back as far as 2008.

The figures show renting now has become even less affordable than it was in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, as interest rates started rising from late 2009 through 2010.

The figures examine what percentage of rentals a household in each income group would be able to afford without spending more than a quarter of their earnings on rent.

Nationally, only 39 per cent of properties advertised for rent on realestate.com.au between July-December 2023 met that definition of affordable for the median, or middle, income household earning $111,000 a year.

“The deterioration in affordability has been driven by the significant increase in rents that we’ve seen since the pandemic, which wages have not kept pace with,” observed PropTrack senior economist Angus Moore.

“Rents nationally are up 38 per cent since the start of the pandemic.”

Over the same period, the national median household income has increased by just half that level.

Renting ‘effectively impossible’ for low income households without government support

The situation is far worse for low income households, with those at the 20th percentile of incomes ($49,000 a year) unable to comfortably afford virtually any of the rentals advertised online.

At the 30th income percentile, earning $67,000, just 3 per cent of advertised rentals would have cost less than a quarter of their household income.

In a cruel irony, over the five years since financial year 2018-19, rents for the most affordable properties have increased much faster than those for the most expensive properties, putting affordable rentals further out of reach for lower-income households.

A rental at the 10th percentile has gone up 43 per cent since 2018-19, from $280 per week to $400 currently.

The report notes that a large part of this trend has been due to the increased popularity of traditionally cheaper regional and smaller metropolitan city markets since the pandemic started.

Mr Moore said “renting is extremely challenging” for lower income households without some form of financial assistance.

“This highlights the importance of rental support for low-income renters, such as Commonwealth Rent Assistance,” he noted.

“Without support, renting would be effectively impossible for many of these households.”

The PropTrack report argues that Rent Assistance should be increased again, following last September’s 15 per cent increase to the maximum rate, worth up to $31 a fortnight.

Policy think tank the Grattan Institute has repeatedly argued that increase should have been almost three times higher, at least 40 per cent on previous levels.

Want a cheaper rental? Move to Victoria

Victoria is currently the cheapest state, relative to incomes, in which to rent a home, and the only one with an affordability index of around 1, which PropTrack said is the level at which all households can afford homes in proportion to their incomes.

That means about half the rental properties advertised cost less than a quarter of the income of a middle-income household, 40 per cent meet that definition of affordability for a household at the 40th percentile of income, and so on.

It is a dramatic turnaround in relative rental affordability for a state that was the second least affordable as recently as 2016-17.

Rents in Melbourne and regional Victoria have increased far less since the pandemic started than most other areas, and the median rent in Melbourne is now $50 a week cheaper than Brisbane and Perth, with a whopping $150 a week gap to Sydney.

On the other end of the spectrum, New South Wales has regained its dubious honour of being the most expensive place in the country to live, particularly in Sydney where the median weekly rent is $750 for a house and $680 for a unit.

While NSW has been the most expensive place to rent for the vast bulk of the past 17 years, Tasmania briefly took that position for three years during the pandemic period (2020-21 to 2022-23). It has slipped back to being second least affordable.

Meanwhile, Queensland has consistently been the third least affordable state to rent in since 2017.

Mr Moore argued there is only one long-term solution to the current affordability crisis.

“Rents are growing quickly because rentals are extremely scarce at the moment, with incredibly low rental vacancy rates around the country,” he observed.

“The only way to solve that, sustainably over the long term, is to have more rentals where people want to live. And that means building more homes.”

The federal government has announced a joint target with the states of building 1.2 million new homes over the next five years.

However, economist estimates based on recent ABS data suggest only around 160,000 homes might be built over the coming year, well short of the 240,000 a year needed to keep up with the target.

The report comes a day after Luci Ellis, Westpac Group chief economist (and former assistant Reserve Bank governor), said the RBA would have concerns about the state of the housing market right now.

She said RBA officials knew their rapid interest rate hikes were exacerbating Australia’s housing problems.

“The issue at present is the low rate of new production of housing in the context of high construction costs and ongoing (if more moderate) population growth,” Ms Ellis said on Friday.

“New housing construction is one of the most important channels of the transmission of monetary policy, both here and overseas. The current low rate of dwelling investment is therefore an expected outcome of the RBA’s policy actions.

“To the extent that higher interest rates have dampened dwelling investment, however, they exacerbate Australia’s current housing affordability challenges in the medium term,” she said.