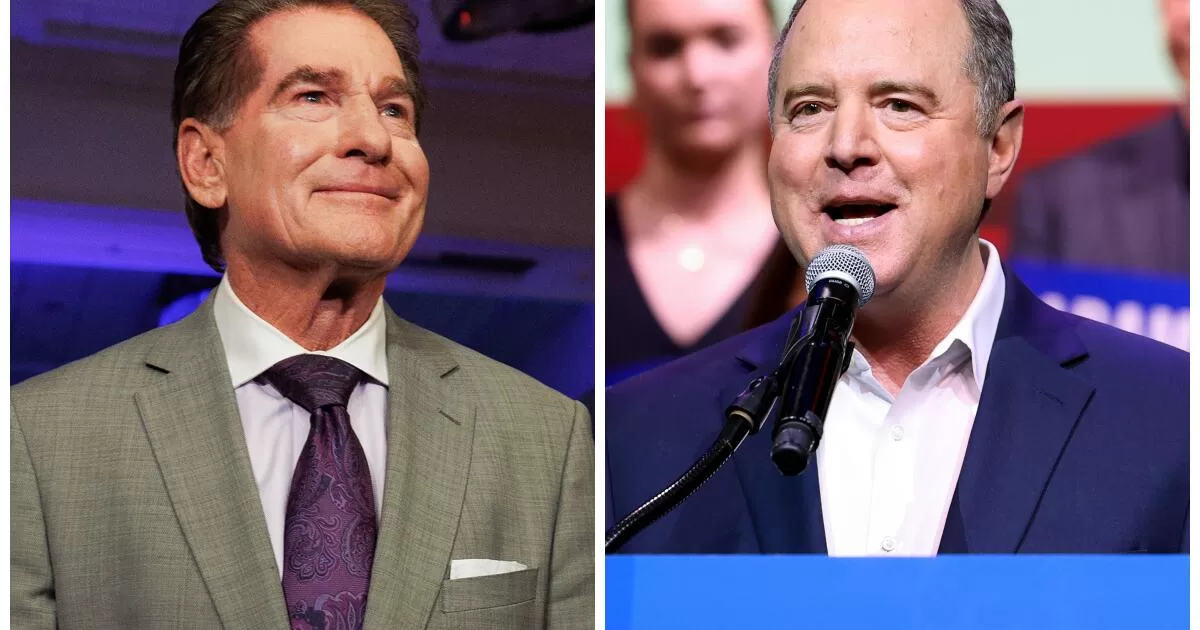

After months of close campaigning, the results were definitive: The Associated Press called the race for Schiff less than half an hour after polls closed and at about 9 p.m. for Garvey. The other top Democratic challengers, Reps. Katie Porter of Irvine and Barbara Lee of Oakland, were running in third and fourth place, respectively.

Schiff, Porter and Lee campaigned for more than a year to replace the late Sen. Dianne Feinstein, who had represented California in the Senate since 1992. Garvey, a Republican, entered the race in October.

The job, one of the most coveted in California politics, is rarely open. Feinstein was in the Senate for more than three decades, and Sen. Barbara Boxer served for nearly a quarter-century. A Senate seat can also be a launching pad for higher office, as was the case for Vice President Kamala Harris, President Nixon and California Gov. Pete Wilson.

For the first time in a generation, Californians may not be represented by a female senator. Boxer and Feinstein were both elected in 1992, the so-called Year of the Woman in American politics. Whoever wins November’s contest will serve alongside Sen. Alex Padilla, who was elected in 2022.

The results were called so early Tuesday that many Schiff and Garvey fans hadn’t arrived at their candidates’ victory parties. As MSNBC projected Schiff’s win, a weak cheer echoed through the Avalon Theater in Hollywood, where Schiff supporters were still negotiating the security line and buying drinks at the cash bar.

After a performance by R&B artist Aloe Blacc, Schiff took the stage about 9:45 p.m., telling the crowd that he had faced stiff head winds from Republican leaders in Washington, including former House Speaker Kevin McCarthy of Bakersfield, from the first day of his campaign.

“At the urging and badgering of Donald Trump, the Republicans censured me for holding him accountable, and then Trump would attack me rally after rally after rally,” Schiff said. “And all those things were basically what we would call Wednesday. But you had my back, every step of the way.”

As Schiff tried to thank his family, about two dozen protesters interrupted, chanting, “Let Gaza live,” and “Cease-fire now.” Schiff has not called for a permanent cease-fire in the Israel-Hamas war.

As the protesters pushed closer to the stage, a campaign staffer and a security guard gestured for Schiff to leave. But he kept trying to speak over the noise, telling the crowd about the storied legacies of Feinstein and Boxer, and thanking his family and the voters of California, before walking off stage.

In a hotel ballroom in Palm Desert, a few hundred Garvey supporters sipped margaritas and ate appetizers. Some held signs showing a stylized version of Garvey swinging a bat in his Dodgers uniform.

“Welcome to the California comeback,” Garvey told the crowd. “What you are all feeling tonight is what it’s like to hit a walk-off home run. … Keep in mind, this is the first game of a doubleheader. So keep the evening of Nov. 5 open, as we’ll celebrate again.”

Garvey said his victory was a sign that Californians are ready for change — though he acknowledged that in a left-leaning state, his path forward would be difficult. He urged voters who were concerned about the U.S.-Mexico border, the economy, the homelessness crisis and crime in major cities to join his campaign.

As Garvey, his wife and two of their grown children walked off stage, John Fogerty’s “Centerfield” began to play, and several supporters started line dancing.

In Long Beach, disappointment over Porter’s lackluster election returns slowly spread through the Bungalow, a trendy midcentury modern cocktail bar. There were no televisions turned on, and hundreds of people were glued to their phones looking at the results.

By the time Porter took the stage with her 12-year-old daughter, Betsy Hoffman, shortly after 9:30 p.m., it was clear that she had lost.

“While the votes are still coming in, we know that tonight we will come up short,” Porter said. “Let me also say this: Our opponents threw every trick — millions of dollars — every trick in the playbook to knock us off our feet, but I’m still standing in high heels.”

Lee did not hold an election night party. Just after 7 p.m., she walked into her downtown Oakland campaign office to greet and hug more than a dozen people who were still phone-banking.

Lee’s fundraising fell far behind that of Porter and Schiff, who are among the House’s most prodigious fundraisers. She said in an interview that she hopes the election results show voters that campaign finance rules have to change, because “money drives the polling in California.”

Asked whether her appeal to progressive voters hurt Porter’s chances of advancing, Lee said: “You’d have to ask her that.” By 8 p.m., Lee was heading to the airport for a red-eye flight back to Washington.

The statewide election brought Schiff, Porter and Lee — all popular Democrats who work together in Congress — into a collision course for the first time, forcing California voters to parse their granular differences on the liberal spectrum.

The candidates tried to emphasize their unique flavors of progressive politics. Schiff focused on his decades of experience in Washington, including his high-profile work as the lead House manager for President Trump’s first impeachment trial and his role on the Jan. 6 House committee. Porter struck a populist tone, promising to stand up to corporate influence in Washington. Lee leaned on her longtime progressive, antiwar credentials. And Garvey painted himself as an antidote to what he called California’s failed liberal leadership.

The dynamics of the race were also shaped by California’s unusual “jungle primary” system, in which the top two vote-getters advance to the general election, regardless of party.

In an effort to box Porter out, Schiff and his allies staged what amounted to a free advertising campaign for Garvey, running political ads across the state calling the former Dodgers and Padres first baseman “too conservative for California” — focusing conservative voters’ attention on him — and framing the election as a two-man race.

Garvey, who launched his campaign months after the Democratic front-runners, has barely been seen in public and did not hold any campaign events in the days leading up to the election. He has seen his support surge in recent weeks, coinciding with Schiff’s flurry of advertising, as he consolidated support from Republicans, who make up about one-fourth of California’s registered voters.

In a state where Democrats have a 2-to-1 voter registration advantage, Schiff’s odds will be most favorable facing a Republican one-on-one in November. He will be an overwhelming favorite, opening with a 53%-to-38% lead over Garvey in a two-way matchup, according to a poll released last week by the UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies and co-sponsored by The Times.

Negotiations over a potential government shutdown kept Lee, Porter and Schiff in Washington until the final few days of the election. They all crisscrossed the state in the waning hours of the campaign, making their final case to voters.

Schiff rented a private plane, stopping in seven cities in two days, including San Diego, Sacramento, San Francisco and Salinas. He trotted out support from high-profile Democrats, including former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Robert Rivas, the new speaker of the California Assembly.

“Why do you think about 80% of our colleagues from California have endorsed Adam Schiff for Senate?” Pelosi told the crowd at a Sunday evening event in the Dogpatch neighborhood of San Francisco. “Because they know that he knows the Congress, and he knows California.”

Porter voted with her 18-year-old son in Irvine on Saturday and swung through San Francisco on Sunday. A crowd at Manny’s, a local community space and cafe in the Mission District, cheered as Porter told them that she had not taken money from corporate political action committees and that the election was “a chance for us to define California as the cutting edge of democracy.”

San Francisco resident Jared Barnes, 36, said he was backing Porter because he relates to what he called her no-nonsense style.

“She’s not a politician, and that’s what I love about her — that authenticity,” Barnes said. “I like helping the underdog who is going up against the political elite.”

Lee focused on voter-rich Southern California in the final days of the campaign, rallying supporters in the Inland Empire, San Diego, Orange County and Los Angeles. On the second floor of an Irvine bowling alley, she referenced her support for a cease-fire in Gaza, and told the crowd: “When people ask what the differences are between myself and my opponents, I just have to say, there are more differences than similarities.”

Alan Vargas, 22, of Corona has been sharing enthusiastic videos about Lee with his nearly 50,000 TikTok followers. Vargas wasn’t yet born when Lee cast her famous, lone vote against the authorization of military force in Afghanistan in 2001, but said it was a pivotal reason why he supported her Senate run.

“She seems to be the only voice out there that’s just taking a stand and being bold and brazen about what she believes in, like young people do,” said Vargas, who said Lee’s progressivism and antiwar politics are uniquely aligned with his values as a member of Generation Z.

Laguna Beach resident Katie Loss, 69, was initially excited that, after a redrawing of California’s electoral maps, Porter would be representing her city in Congress. Loss liked Porter’s hard-charging style, and had contributed more than $1,000 to her House campaigns in 2020 and 2022.

But Loss was dismayed when, three days after being sworn in, Porter said she would run for Senate. The timing of Porter’s announcement made Loss, as a new constituent, feel that “our district was not her priority,” she said.

Instead, Loss is supporting Schiff, who she said she has long admired for his intelligence, his more than 20 years of experience in Washington and his willingness to stand up to Trump. And, she said, his polite, unflappable demeanor is “badly needed in the Senate.”

Though no longer in the Oval Office, Trump has become a major talking point in the campaign: Garvey, who voted for the former president twice, has not said whether he will vote for him again, and the Democrats have used the former president’s name to burnish their liberal bona fides.

Lee said she was one of the earliest supporters of impeachment, as well as the lead plaintiff in a lawsuit against Trump over his role in the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection. Porter talked about impeachment too, as well as her forceful interrogations of Trump appointees on the House Financial Services Committee.

Still, Schiff — through his role as a House impeachment manager and regular appearances on cable news — was the most visible and forceful foil to Trump, who regularly criticized him at rallies and insulted him on social media.

That high-profile role helped Schiff raise millions in campaign funds. His campaign reported spending more than $22 million on advertising in about six weeks.

Though a prodigious fundraiser herself, Porter’s numbers lagged behind Schiff, who coasted to reelection to a 12th term in the House in 2022 and left millions untouched in his campaign account. Those funds provided a multimillion-dollar cushion to kick-start his Senate campaign.

Lee struggled to raise enough money to mount a statewide advertising campaign, which costs millions of dollars.

Both she and Schiff had pledged not to accept campaign contributions from corporate political action committees, a practice that Porter has followed since she first ran for office in 2018.

Porter repeatedly criticized Schiff for previously accepting campaign funds from political action committees funded by corporations — including oil, pharmaceutical and financial firms — seeking to influence federal policy in Washington. She told him at a recent debate: “I didn’t realize how much dirty money you’ve took until I was running against you.”

Schiff argued that Porter had accepted contributions from people who work in the oil industry, on Wall Street and for pharmaceutical companies — and that she had accepted contributions from Schiff in the past without complaint. A Times analysis of federal campaign data showed that Schiff’s two fundraising committees contributed $54,675 to Porter while she was running for the House.

The problem with the “purity tests” like the ones Porter has laid out, Schiff said at a recent debate, is that “invariably, the people who establish them don’t meet them.”

The race was also shaped by more than $21 million in spending by outside groups, including an independent expenditure committee called Fairshake that spent more than $10 million to oppose Porter’s candidacy. The group, funded by cryptocurrency investors, aired ads statewide (and hired a plane to circle the Hollywood Hills, towing a banner) that painted Porter as a hypocrite and an actor.

Times staff writers Hannah Fry, Julia Wick and Anabel Sosa contributed to this report.