But the Houthi attacks on shipping routes in the Red Sea have upset this consensus. As Iran officially denies any direct involvement despite its unquestionably close relationship with the Houthis and Saudi Arabia remains strategically quiet after the end of its protracted and costly conflict with the armed group, Beijing finds itself in an awkward position.

China has a great deal at stake and has made no secret of its opposition to the attacks. As the world’s largest exporter of goods and one of the top players in the global shipping industry, it has a tremendous economic stake in maintaining the security of shipping lanes.

In this context, the United States has tried to cajole China into bringing its influence to bear on Iran to stop the attacks, but there has been no major movement from Chinese diplomats in that direction. This reflects the reality that Beijing has only limited sway over Tehran and the US itself is much more capable at bringing the Red Sea crisis to an end by simply using its leverage over Israel.

The limits of Chinese influence

The importance of the Red Sea shipping lanes for China cannot be overstated. The majority of Chinese exports to Europe pass through the Suez Canal, and Chinese companies have just recently signed $8bn worth of investment deals in the Suez Canal Economic Zone.

Although the Houthis have pledged not to attack Chinese ships (as long as they are not bound for Israel), China has still suffered substantial economic damage from the crisis. Shipping and manufacturing have been impacted across the country with many businesses at all levels of the supply chain complaining of devastating losses.

China has been reluctant to directly condemn the Houthis or publicly link them to Iran, but it has repeatedly voiced its disapproval, calling on all parties to respect the freedom of navigation and “stop attacking and disturbing civilian ships”.

In January, the Chinese media outlet Global Times reported that Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi had said, “China has been making active efforts to ease the tension in the Red Sea.”

Then a Reuters article claimed that China had communicated a vague but threatening statement to the Iranians: If Chinese vessels or economic interests were to be impacted by the Houthi attacks, it could harm Sino-Iranian business relations.

The Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs denied the report, but Islamic Republican, an official Iranian newspaper, published an article criticising the “selfish demand” of the Chinese, claiming that China showed a willingness to “help the Zionist regime” and advised it not to “extend your legs beyond your own carpet”. (In other words, stay out of it.)

A US official told the Financial Times that there were “some signs” that China is exerting pressure but that its impact is unclear.

Then in February, media reports emerged of Beijing sending three warships to the Red Sea. However, few reported the fact that such missions are routine. China has sent more than 150 warships to the Gulf of Aden since 2008, and the three ships were dispatched to relieve a group of six that had sailed to the Red Sea in October, representing a downgrade of Chinese forces in the region.

These developments raise an important question: Just how much influence does China have over Iran? At a first glance, the answer seems to be quite a lot. China purchases the majority of Iranian oil and is also a key supplier of weapons and high-tech surveillance equipment to the Iranian security forces. It is also Iran’s top trade partner and is committed to a variety of proposed projects to enhance trade, investment and other forms of bilateral cooperation over the next 25 years.

However, a closer look reveals a more complicated picture. While China does purchase the majority of Iranian oil, most is bought illicitly by private “teapot” refineries, not Chinese state refineries, which are much more wary of breaching US sanctions.

Moreover, China is under a great deal of economic stress at the moment, and oil processing companies may not be willing to forego the deep discounts Iranian suppliers are willing to offer. As it stands, there is already a disruption in the flow of Iranian oil to China, and it is caused not by Beijing but by Iranian oil suppliers locked in a “stalemate” with Chinese refineries over the steep discounts they demand.

Finally, while China has committed itself to a number of investment projects in Iran, it hasn’t actually followed through, and Iran lags far behind other Middle Eastern nations in terms of Chinese foreign direct investment.

In short, China has some influence with Iran but has difficulty converting it into leverage.

Why China? Why not the US?

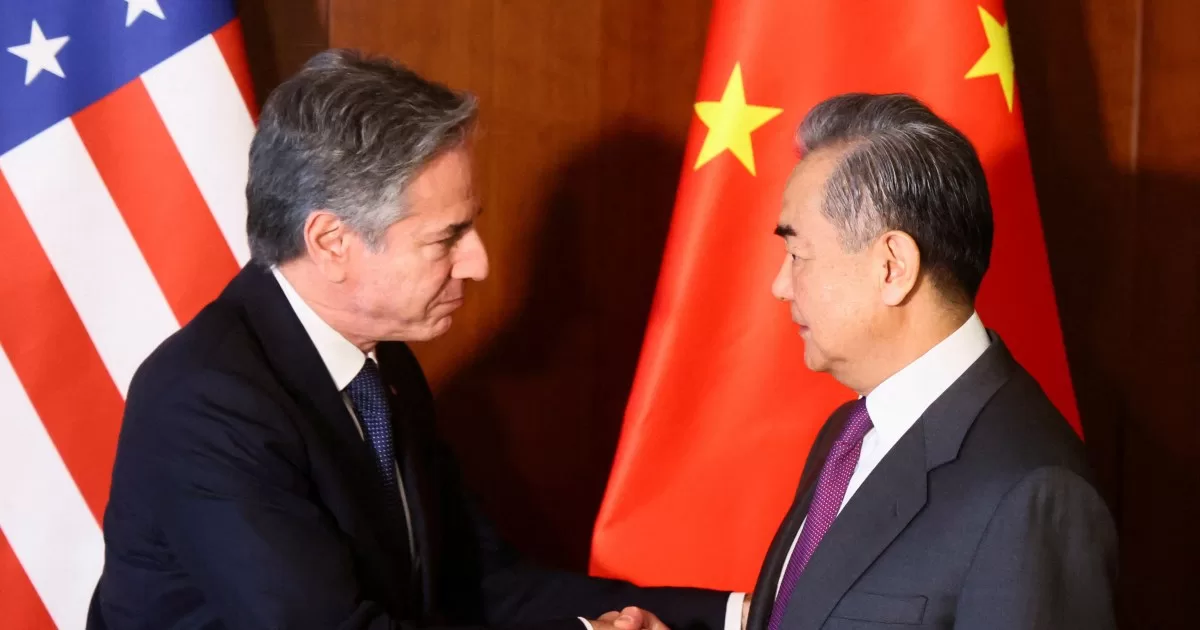

And yet, the US continues to insist that China can press Iran on the situation in the Red Sea. The subject was raised during a series of meetings between US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan and Wang in Bangkok in late January.

Washington seems convinced that Beijing is unwilling to place any meaningful leverage on Iran. One senior official told reporters, “Beijing says they are raising this with the Iranians, … but we’re certainly going to wait before we comment further on how effectively we think they’re actually raising it.”

As the US has conducted more military strikes in the region, China has grown more agitated about a potential escalation. Wang has repeatedly made clear Beijing’s unease, stating, “We believe that the [United Nations] Security Council has never authorised any country to use force against Yemen, and therefore, one should avoid adding fuel to the tensions in the Red Sea and raising the overall regional security risks.”

China may be feeling pressure from the disruptions to global shipping, but a wider conflict between the US and Iran has the potential to threaten its entire economic strategy in the region. Beijing has been clear that it believes the best way to calm the situation down is a ceasefire in Gaza, which the Houthis have clearly said would result in an end to their strikes.

Certainly, it is quite odd that the US is insisting China use influence it does not necessarily have over Iran and the Houthis but it does not consider using its own diplomatic weight to restrain Israel and bring the war in Gaza to an end.

Washington has a tremendous amount of economic, military and political leverage over the Israeli government, but it refuses to use it. Instead, it is sending arms to Israel in the midst of its brutal campaign of collective punishment against the people of Gaza, which legal experts and the International Court of Justice have said may amount to genocide.

Indeed, claims by US officials that China has an “obligation” to pressure Iran and restrain the Houthis ring hollow when the US refuses to use its substantially larger influence over Israel – the one state that is showing the least restraint of all.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.