Many of the confections will be familiar to international visitors: red velvet cupcakes, jam swiss rolls and custard doughnuts. But others can only be found in certain parts of Cape Town: fragrant “koesisters” dusted with desiccated coconut, meringue-topped “Hertzoggies” and garish pink-and-brown “tweegevrietjies”.

[Desmond Louw, DNA Photographers/Al Jazeera]

Unlike the man it is named after – the Afrikaner nationalist JBM Hertzog, who first came to power a century ago – the Hertzoggie is a bite-sized delight. A crisp biscuit shell is filled with chunky apricot jam and topped with delicately spiced coconut meringue before being popped in the oven for a final singe. The cookie was invented by Hertzog’s white, female supporters in the 1920s, and continued to be baked at National Party – the party that would go on to implement apartheid in 1948 – events for decades to follow.

But the Hertzoggie would also find favour among a different segment of the population.

“Hertzog made two promises,” explains chef Cass Abrahams, a legendary Muslim cookbook author and radio personality who was responsible for bringing the centuries-old cuisine of her people to a wider audience from the 1970s onwards. “He said that he would give the women the vote, and hy sal die slawe dieselfde as die wittes maak (he would make the slaves equal to the whites).” Her choice of words is not accidental: Almost two centuries after the abolition of slavery, Abrahams and the Cape Malay (the descendents of enslaved Muslims from Indonesia and elsewhere) community have not forgotten their history of bondage.

“Cape Malay women became terribly excited by Hertzog’s promises,” Abrahams continues. “So, they baked their own, spicier version of the Hertzoggie … for a while.”

After the events of 1930, when Hertzog broke the second of his promises, by leaving women of colour disenfranchised, Coloured women returned to their ovens to bake a sarcastic version of the Hertzoggie: the crudely iced and sickly sweet pink-and-brown tweegevrietjie, or two-faced cookie, which lacks the delicacy and refinement of the original – deliberately so. “Women would bake them both and put them next to one another and tell their children the story of General Hertzog,” says Abahams.

Both versions are still baked today, a familiar sight at Cape Malay teas, weddings and funerals – and “especially at Eid”, Abrahams adds. The Wembley Bakery sells about 1,500 classic Hertzoggies and 800 tweegevrietjies in an average week.

Recipe for disaster

In the 1920s, South African politics was all about the so-called “native question” – that is, coming up with a workable solution to the inconvenient and incontrovertible truth for the white minority, that people of colour far outnumbered those with white skin. The Union of South Africa had only been established in 1910 – the Anglo-Boer War only concluded in 1902, and thanks to a hastily agreed hodgepodge constitution, different provinces had different voting rules. Men of all races could vote in the Cape Province (providing they met the property and literacy franchise qualifications), but only white males could vote in the three other provinces: Transvaal, Natal and Orange Free State.

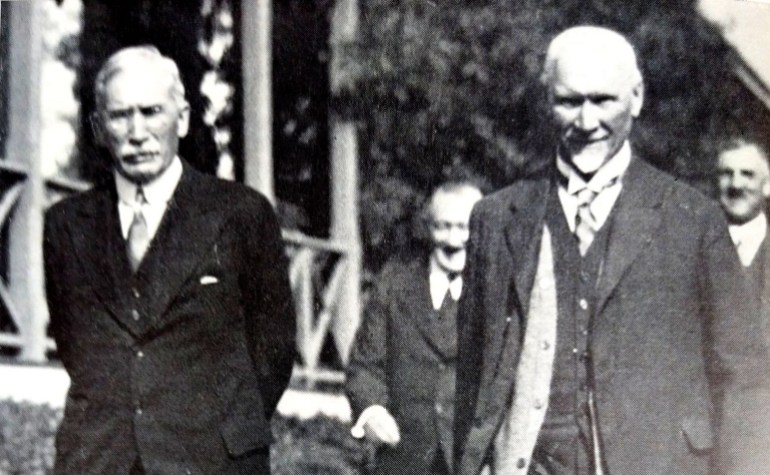

Prime Minister Jan Smuts declined to tackle the “native question”, preferring, as his biographer Richard Steyn puts it, “to kick the can down the road” in the hopes that the question would answer itself. Smuts’s bitter rival Hertzog, on the other hand, had very clear ideas about how to solve the “native question” – and segregation and disenfranchisement were at the heart of these ideas.

From 1919 onwards, Hertzog, as leader of the opposition, made a concerted effort to win the Coloured vote. His “new deal for Coloureds” was simple, wrote Gavin Lewis in his seminal history of Coloured politics in South Africa: “In return for their support of [Hertzog’s] policies, Coloureds would share in the privileges legislated for white workers, and would be exempted from the restrictions applied to Africans.”

Thanks in part to this promise, Hertzog – in coalition with the largely English-speaking, but equally racist, Labour Party – was able to topple Smuts at the 1924 election.

As an aside, Jan Smuts also had a cookie named after him, a jam-filled pastry shell that is very similar to a British “maid of honour”. Peter Veldsman, one of South Africa’s leading culinary historians, explains, “The Jan Smutsies were an out-and-out political reaction from Smuts’s supporters: ‘They’ve got a cookie and we need one, too,’” before adding: “Personally, I prefer Jan Smuts cookies. And not just because my family were Smuts supporters. But I haven’t seen, let alone eaten, one for years.”

One step forward and three steps backward

At the same time, the women’s suffrage movement was belatedly gathering steam in South Africa. While most Western nations granted women the right to vote in the years immediately following World War I, South Africa was slower on the uptake. Its parliament, after all, included men such as TC Visser, who claimed that “it was a scientific fact that the development of a woman’s brain stopped at a stage beyond which a man’s brain went on.”

By the end of the 1920s, however, attitudes had changed and men like Visser were in the minority. Even Hertzog accepted that women should be allowed to vote. And when he announced plans to give both white and Coloured women the vote in the Cape – to “make the slaves equal to the whites” – Hertzoggies began to fly out of Cape Malay ovens.

This enthusiasm ignored the fact that Hertzog was a politician – and a racist one at that. For an idea of his true feelings on the matter, one need look no further than a statement from the Transvaal branch of his own party which declared, in 1928,“Die vrou wil nie saam met die k***** stem nie.” (“The woman does not want to vote with the k*****,” a racist term for Black people.)

After Hertzog’s landslide victory in the 1929 election he realised he could achieve his goals without the support of Coloured voters. The 1929 election has gone down in history as the “swartgevaar” or “black peril” election due to Hertzog’s racist scaremongering tactics, which preyed on white people’s fears that Black men would steal their jobs and rape their women – with remarkable success. It would not take long for his true colours to show: Apartheid may only have been implemented in 1948, but many of its foundations were laid by Hertzog in the 1920s and 30s.

Only in South Africa could allowing women to vote actually take democracy backwards. But that is exactly what Hertzog managed with the Women’s Enfranchisement Act of 1930. By granting a Union-wide unqualified franchise to white women over the age of 21, Hertzog reduced the Coloured vote from 12.3 percent of the electorate to 6.7 percent overnight. The even smaller Black vote was also effectively halved by the Act.

As the historian Mohamed Adhikari explained, “[The Act] represented an about-face on the part of … Hertzog. Throughout the latter part of the 1920s, he had tried to entice Coloured voters into supporting the National Party with the prospect of a ‘New Deal’ that would give them economic and political, but not social equality with whites. This act was but the latest development in a decades-long trend of the erosion of Coloured civil rights.”

Incensed, Coloured women once again took to their ovens to bake tweegevrietjies or two-faced cookies.

At its base, the tweegevrietjie is identical to the Hertzoggie. But instead of the meringue topping it is adorned with sugar icing: half pink and half brown. Abrahams says it was a visual representation of “the white man with a black heart who broke promises.”

Fatima Sydow, a cookbook author and TV chef who spoke to Al Jazeera before her untimely death in December, interpreted the topping even more literally: “My aunty always told me that, for her, the pink and brown icing was a visual representation of the Group Areas Act that underpinned apartheid. It reminded her that she couldn’t sit on that bench or swim at that beach” – the Act had designated suburbs, beaches, schools, jobs, trains and buses for particular race groups.

What is in no doubt, Abrahams says, is that it was “an act of defiance.” Sydow agreed, “My people could not express themselves vocally because they would be arrested. So, they let their baking do the talking.”

Kitchen politics

While the tweegevrietjie is the most overt example of Cape Malay women exerting power through cooking, this theme goes back to the very origins of colonial South Africa. The first slaves were brought to the Cape from Batavia (Jakarta) in 1653, just one year after the Dutch East India Company established a permanent refreshment station at Cape Town. Malay women quickly became known for their prowess in the kitchen, and the 20th-century food historian C Louis Leipoldt wrote that “slaves who had knowledge of this kind of cookery commanded a far higher price than other domestic chattels.”

As Gabeba Baderoon, an associate professor of women’s, gender, and sexuality studies at Penn State University wrote in Regarding Muslims: From Slavery to Post-Apartheid, “the kitchen formed an unrelenting, perilous and transformative arena in which an uneven contest between slave-owner and enslaved was fought. Ultimately enslaved people came to shape South African cuisine in unexpectedly potent ways.”

“What makes the Hertzoggie and the tweegevrietjie so special,” Abrahams adds, “is that people from the East, where our slave ancestors came from, don’t eat baked sweet treats. Even today, many people on the islands of Indonesia don’t have ovens. Our wonderful baked goods enjoy a direct influence from the Europeans. But we made them our own.”

Cape Malay cooks became famous for what Leipoldt referred to as “their free, almost heroic use of spices” and over the centuries countless Cape Malay dishes have come to be cooked in kitchens across the country.

From the middle of the 20th century, several white authors published Cape Malay cookbooks based on interviews with Cape Malay cooks.

But, Abrahams tells Al Jazeera, “every single one of those recipes left at least one key ingredient out,” because the authors’ Muslim informants refused to give away all their secrets. “The whole thing boils down to empowerment, the power they held in their cooking,” she says. “That’s why they didn’t share recipes.”

Abrahams, who published her first cookbook in 1995, was one of South Africa’s first Muslim cookbook authors. “I got a lot of pushback,” she remembers with a laugh. “People would say ‘Why are you sharing our secrets with the ‘witmense’ (white people)?’ But I told them, no man, it’s everyone’s food.” Since then, subsequent generations of Muslim cooks, like Sydow and her sister, have found it easier to reveal the secrets of Cape Malay cooking in cookbooks, on TV shows and even on YouTube.

But, with a few exceptions, the story of the Hertzoggie and the tweegevrietjie hasn’t been written down. As Baderoon wrote, “this secret history recounting the memory of a political betrayal is invisible to the unschooled eye. Not even the Muslim authored cookbooks reveal the secret. Instead, the story circulates in oral form in the Muslim community.”

Some stories, Abrahams adds with a laugh, are too risque to be written down. “One woman told me that her grandmother referred to tweegevrietjies as ‘Mary-Annes’ … After the best-known prostitute in Cape Town!”

Jokes aside, the tweegevrietjie was – and still is, according to Sydow – a deeply political bake. “Sometimes, people ask me to create a ‘driegevrietjie’ (three-faced cake),” she said, in reference to South Africa’s continuing political issues. “But I prefer to focus on the positives.”

Nick Dall is co author of Spoilt Ballots: The Elections That Shaped South Africa.