On the eve of Nigeria’s last presidential election, around 4 p.m., Ibrahim Hassan wore one of his finest clothes, grabbed his voter card, exited his tent at the Muna Garage displacement camp, and walked towards the main road where a flock of vehicles waited. He was making an hour-long journey from Maiduguri to his hometown to cast his vote — alongside thousands of other internally displaced people, including his wife, son, and daughter-in-law. By the time the dust settled and all the trucks and buses and cars had driven off, a strange silence settled on the camp. The only people left were those who were too old to travel, those who were too young to vote, and a few others.

Some of those voters would eventually return to the camp a few hundred naira richer — or a little more if they got lucky. Many others would return with growling bellies, empty pockets, and curses under their tongues.

For many IDPs in Nigeria, while the election season may not give them a rare chance to engage their representatives in government and other political aspirants, it presents an opportunity for them to fill their stomachs with nutritious meals, grace their palms with wads of money, and maybe even add fresh yards of clothing to their collection, so long as they vote for particular candidates. It may not seem like a mouthwatering deal, but for a displaced person who has gone several days without decent food and who is not certain where his next wage will come from, it is a much better use of their day than idling around or voting simply based on conviction.

And the political parties know it.

HumAngle spoke to many internally displaced people across northeastern and northwestern Nigeria who confirmed that they were targets of vote-buying and intimidation during elections. A lot of them also said they have been treated like second-class citizens since their displacement and have not benefited much from the freedoms and powers that naturally come with a democratic system.

There are over 3.3 million internally displaced people in Nigeria, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Out of this number, 2.3 million are in the North East — of which 42 per cent are above the age of 18. Borno state alone is home to 1.7 million IDPs. Some of them said during last year’s elections, the majority of those who voted in their communities were displaced people brought in from camps many miles away. Auwal, an IDP living in the Shuwari resettled community, remembers that three large schoolbuses and three dump trucks, known locally as Yellow Buckets, were used to convey hundreds of displaced people from Maiduguri and its outskirts to the Gulumba area of Bama.

Ibrahim Hassan was young when he first voted, maybe even too young. He says he is 53 now, but the first time he voted was in August 1979 during the tightly contested presidential election that ushered in Shehu Shagari’s administration. “We voted for the winning team,” he said, thumbprinting the air before him as he remembered those days with pride.

Back in Malumri, his village in the Mafa area of Borno state, northeastern Nigeria, politicians used to visit the locals to solicit their votes, and then they decided for themselves. That stopped after their displacement.

When Boko Haram insurgents unleashed violence in Maiduguri, Borno’s capital city, in 2009, news of it trickled down to Malumri. The boots and bullets soon followed. The terrorists arrived in his community and frequently snatched their goats, cattle, and donkeys. When that wasn’t enough, they started imposing strange rules, such as, ‘Women can no longer go out to fetch water.’ One night, Ibrahim, his family, and over a hundred people left for Mafa town. Some order had been restored to Maiduguri at this time, so they made their way down, trekking the whole 50 or so kilometres. The journey took two days.

First, they camped at a filling station where humanitarian workers shared loaves of bread and canned fish with them. Three days later, soldiers relocated them to what is now the Muna displacement camp.

“They told us that we were going back to our village after three months. We believed them,” Ibrahim recalled. “But here we are after nine years. Malumri is still not safe.”

The decade-long displacement has affected many things, from their livelihoods to their relationships and access to basic amenities. But one of the least-discussed consequences is its impact on their political freedoms.

For one, thousands of internally displaced people are not able to exercise their right to vote due to the lack of an enabling environment.

In 2015, Nigeria introduced a policy framework that stipulates how elections are to be conducted for the benefit of IDPs, who often live in camps that are a long distance from their home communities. In many cases, their communities cannot be accessed safely by government officials due to the presence of violent non-state actors. To get around this difficulty, the framework proposed that voter registration exercises should be done at displacement camps, and provision should be made for the distribution of permanent voter cards (PVCs) in the same location. Also, voting centres are to be established either at the camps or in central locations.

In reality, however, voter registration exercises did not take place in many IDP camps, nor did voting itself. Thousands of IDPs were instead transported to cast their ballots in their local government areas of origin. One 2023 study discovered that while the vast majority of displaced people in northeastern Nigeria believed in the electoral process and were keen on voting, about a quarter of them were unable to get their PVCs. Reasons for this include lack of awareness about the registration process, loss of cards, tediousness of registering, lack of nearby registration points, and absence of feedback after registering.

The forceful closure of camps in Maiduguri has also contributed to the disenfranchisement of IDPs. Nine camps were shut down between May 2021 and December 2022, a move that affected over 153,000 IDPs. Many of those who were resettled complained that they could not vote because they were assigned to polling stations in Maiduguri, not those in their new location, and they did not have enough money to travel just for the elections.

Many IDPs express nostalgia for the political freedom they enjoyed before their displacement. Auwal, for example, said representatives of different parties used to court members of his community. They collected money from all the parties and voted for whichever they wanted. Now, he contrasted, “We do whatever they ask us to do; we are like prisoners.”

It is as if they are a voting bloc that has been auctioned off to the ruling party, he says. “There is no food. There is no money. But they will bring vehicles, and we will go and vote for them by force.”

When the vehicles took off that day in February 2023, they dropped the IDPs in their respective local government areas. Ibrahim, whose polling unit is in the Gawa ward of Mafa, passed the night at the residence of an official of the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC). They prepared tuwon shinkafa (rice swallow) and served everyone. It was the only food they would be served in two days, but that wasn’t the only problem.

“We asked what of the money. They told us we would get it the next day. The following day, we didn’t even get breakfast. We lined up for hours to get accredited and vote. After we voted, they shared ₦200 each (13 cents). You can’t even buy bread with that amount,” he protested.

“Some got ₦300 or ₦400. We asked why the money was not complete, and we were told to be patient and that they would share yards of clothes when we returned. They later shared five yards, but not everyone got it. Some of the ladies got wrappers. Most people didn’t get them.”

During the 2019 general elections, he was offered ₦400, which wasn’t a lot either, but Ibrahim said he felt like he had more freedom then. He said the conditions were even worse during the governorship elections in 2023, as nobody paid them any regard after they were transported to vote.

Voters in Bama complained of going the whole day without food, too. Those with money bought bread and soda. “Those who didn’t have money to eat were starved; they looked like they would die,” observed Auwal, who asked to be anonymous because he is a prominent figure among his people. During the presidential election, the party agents gave voters at his unit ₦2,000 ($1.3) each. During the governorship election weeks later, they distributed sachets of Maggi and laundry soap.

Ali Kache, 60, who voted in Boboshe, a community in Dikwa local government area, said they received ₦2,000 on the eve of the election day. The following day, they received an additional ₦700. It was only enough to get him food and water. If not for the money, he may not have voted as he did, he admitted, laughing. “The government provided free transport, and since we have already gone, we just have to vote.”

He added that the opposition People’s Democratic Party (PDP) also gave people money, but only after confirming they voted for it. He claimed the party handed them between ₦500 and ₦1,000.

Displaced voters did not starve everywhere trying to exercise their civic duty. Modu Abatcha, 59, who voted in the Mujigne ward of Mafa, recalled they ate thrice that day and that more than 10 cows were slaughtered for their pleasure. The food cannot be compared to what they are used to at the camp, he said.

Musa, an APC ward secretary who asked for his real name not to be published, confirmed the distribution of materials. But they got more than Maggi cubes and small change, he said. In one unit, the party shared 74 pieces of 5-yard clothing for men, 100 pieces of wrappers for women, and ₦190,000.

HumAngle shared its findings and the allegations with the APC and PDP spokespersons in Borno, but we have yet to get responses from them despite calling their phones on multiple days and sending texts.

Ibrahim admitted many of the IDPs who followed the buses and trucks to exercise their right to vote did so because they expected something in return. Political parties then exploited this desperation. “They did this because IDPs don’t have any choice,” he suggested, a sentiment that was echoed by several others. And if the people complain, he says, the politicians simply oil the cracks with more lies, assuring them that even if they do not meet their needs today, they will surely do so at another time.

For many years, vote-buying has been the staple of the Nigerian political scene. People aspiring for public office use cash, food, and other items to manipulate the electorate in their favour. In a survey conducted in 2019, 21 per cent of adult Nigerians reported that they were personally offered money or some favour in exchange for their vote. Another survey by NOIPolls found that nearly a third of Nigerians were willing to sell their votes during the last general elections. It doesn’t help that Nigeria has one of the highest populations of poor people in the world, with 63 per cent of its people (113 million) facing multidimensional poverty. The political exploitation strategy works because of this bleak economic background. High levels of poverty and illiteracy have been identified as some of the greatest push factors for vote-buying.

There are even higher levels of poverty among internally displaced people. The World Bank states that almost nine out of 10 IDPs in Nigeria’s North East fall below the international poverty line of $1.90 per day. In addition to this, six in 10 displaced families are highly food insecure, and, on average, IDPs in the region consume less than a third of the poverty line threshold. Nigeria’s towering inflation rates are not making things any easier. Many displaced have become so poor that they resort to eating leftovers that are ordinarily meant to fatten livestock.

“If you stay, you will not get this ₦2,000. So people went to vote because of it, not anything else,” argued one IDP at Muna camp, who often mobilises support for party candidates during elections.

Ibrahim agrees. Before he became displaced, he had all the food he could possibly need. He sold some of his harvests, and what remained was enough to meet his family’s needs. He also had lots of livestock. These days, however, life is not so easy. “We struggle to eat,” he said. “Some people don’t have food. In my own case, I farmed last year and got two to three bags of grain. When it finishes, we are in the hands of God.”

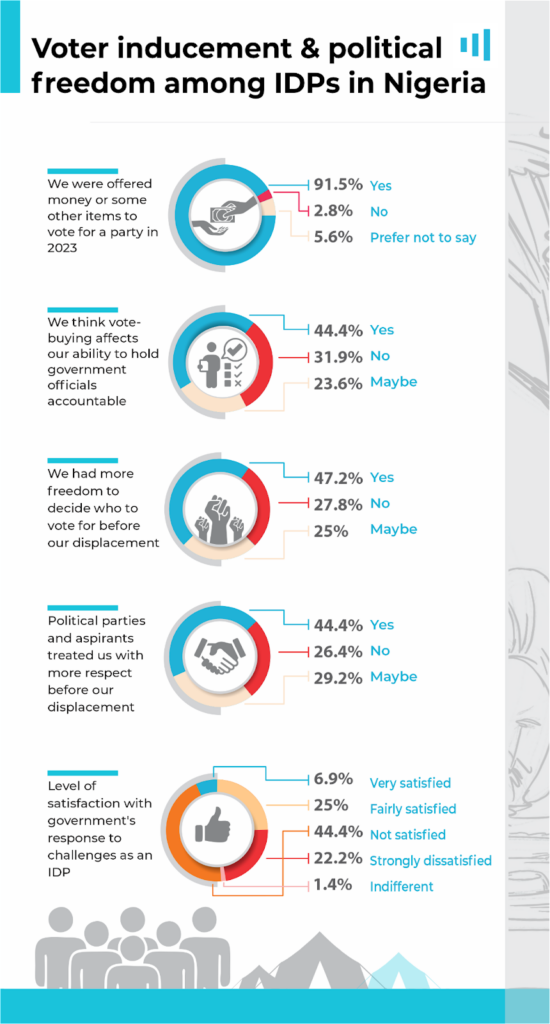

In December 2023, HumAngle conducted a survey of 72 IDPs with voter cards in Borno and Zamfara states that reflected how widespread vote-buying is. The majority of the respondents (91.5 per cent) said they were offered something to vote for a certain party. The inducements included money (ranging from ₦1,500 to ₦10,000), clothing, rice, and soap.

More than four out of 10 respondents agreed that vote-buying affects their ability to hold political representatives accountable, and an additional 23.6 per cent replied ‘maybe’ to the question.

We also asked about how their political status has changed since their displacement. 47.2 per cent said they had more freedom in deciding who to vote for before they were displaced, and an additional one-quarter of respondents said this might be the case. 44.4 per cent also believe political parties and aspirants treated them with more respect before they were displaced, and an additional 29.2 per cent said this might be true.

If financial motivations did not do the job, party officials usually resorted to threats.

When IDPs from Gulumba were transported to vote, some of them openly declared that they planned to vote for the opposition party because the incumbent government was not treating them fairly.

According to Auwal, “the APC officials got confused and said, ‘Listen carefully, if anyone votes for PDP, we will send you away from the camp, and we won’t allow you to go back to your village. The camp belongs to the government, so be careful.’”

Because people do not have an alternative place to live, he said, they felt they had no choice but to vote for the ruling party.

Ibrahim said during the voting last year, party agents, including secretaries and former councillors, monitored the entire process and guided their thumbs along the ballot papers. They warned them not to vote for rival parties. “The agent would know if you didn’t vote for them, and people are afraid they might disturb them afterwards.”

Ali Kache even alleged that military personnel flogged some people who stayed back at the IDP camp and did not go to vote. So it’s almost a given that people have to vote just as the party they vote for is oftentimes out of their hands.

“We, the IDPs, don’t have a choice,” said Yabata Modu, who hails from Boboshe. “They just told us to go, and we went.” I asked her if the politicians promised them anything to wield such an influence. Her response was sarcastic: “Is it not someone who visits and sits with you that will promise you something?”

Musa, the ward secretary, said even party members like him have been treated with disregard since their displacement. He is barely updated about party activities, and six months could go by without anyone contacting him. Previously, however, he was called at least every three weeks, he said. “When we were not displaced, they met us in our homes to present their request. Now, we do nothing. We just focus on farming. They consider us as IDPs, and nobody cares about us.”

I asked Ibrahim if he would make the same decisions next time, looking back at his experience during last year’s elections. Certainly not, he replied, explaining that there was no point leaving his house to vote if he would not get any benefit out of it. If at all he would go to the polling station, he later added, he must first receive whatever the politicians promised in his palms before wasting his time.

“Democracy is nice, but only some people are enjoying it,” he mused. “We at the IDP camp are not.”

This report was done with support from the Gatefield Impact People Journalism Fund.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.