Defence minister says the $7.25bn plan will increase Australian navy’s surface combatant fleet to 26 from 11.

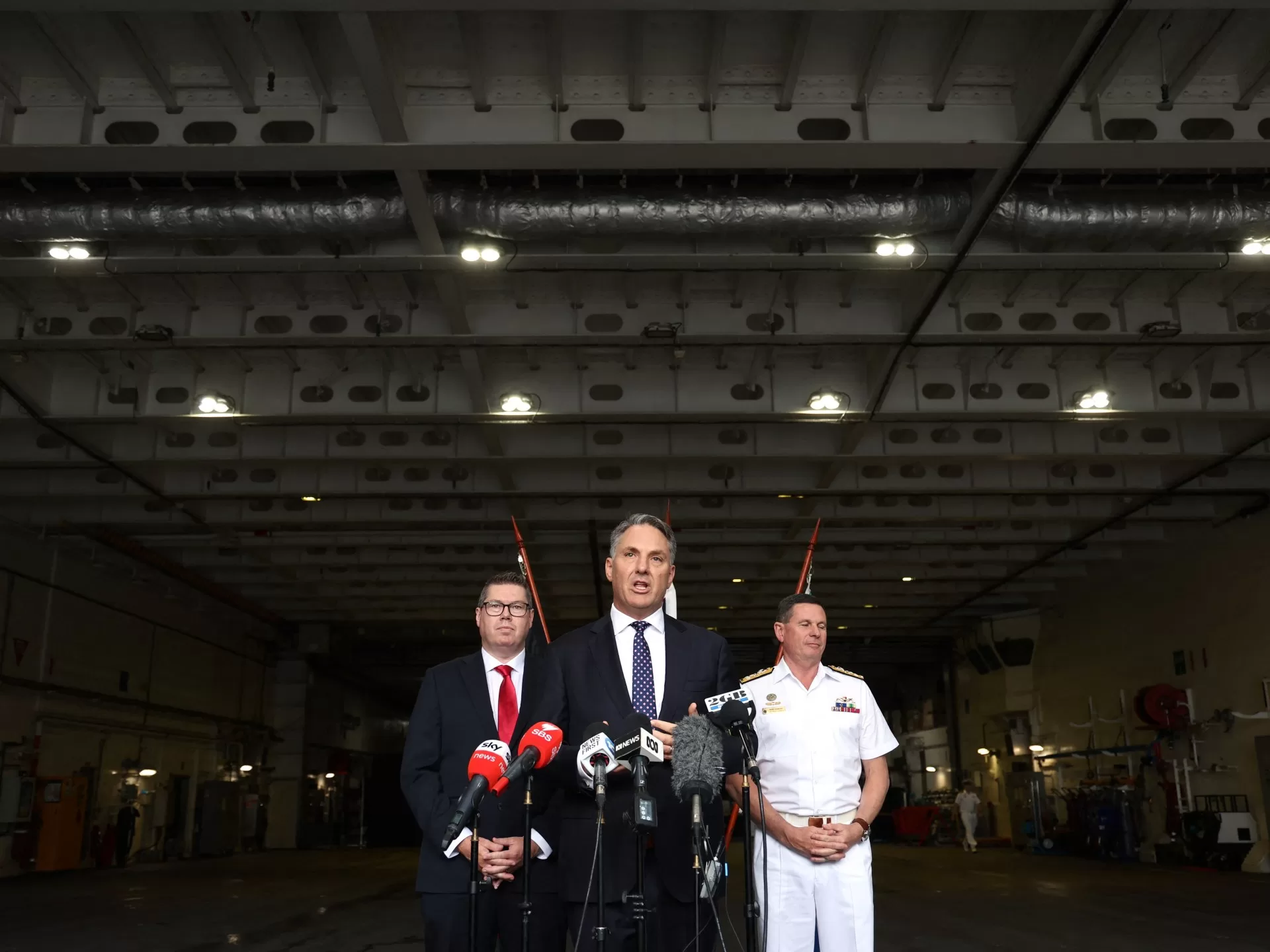

Defence Minister Richard Marles said on Tuesday that the government’s plan would eventually increase the navy’s surface combatant fleet to 26 from 11, the largest since the end of World War II.

He cited concerns over rising geopolitical tensions as competition between the United States, its allies and China heats up in the Asia Pacific region.

Under the new plan, Marles said Australia will get six Hunter class frigates, 11 general-purpose frigates, three air warfare destroyers and six state-of-the-art surface warships that do not need to be crewed.

At least some of the fleet will be armed with Tomahawk missiles capable of long-range strikes on targets deep inside enemy territory – a major deterrent capability.

“It is the largest fleet that we will have since the end of the second world war,” Marles told reporters.

“What is critically important to understand is that as we look forward, with an uncertain world in terms of great power contest, we’ll have a dramatically different capability in the mid-2030s to what we have now,” he added.

“That is what we are planning for and that is what we are building.”

The minister said the large optionally crewed surface vessels (LSOV), which can be operated remotely and are being developed by the US, will significantly boost the navy’s long-range strike capacity.

The vessels could be inducted by the mid-2030s.

Australia will also take steps to accelerate the procurement of 11 general-purpose frigates to replace the ageing ANZAC-class ships, with the first three to be built overseas and expected to enter service before 2030.

“This decision we are making right now sees a significant increase in defence spending … and it is needed, given the complexity of the strategic circumstances that our country faces,” Marles said.

The announcement – which comes amid Australian plans to procure at least three US-designed nuclear-powered submarines – would see Canberra increase its defence spending to 2.4 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), above the 2 percent target set by its NATO allies.

Experts say that taken together, Australia is poised to develop significant naval capability.

But the country’s major defence projects have long been beset by cost overruns, government U-turns, policy changes and project plans that make more sense for local job creation than defence.

Michael Shoebridge, a former senior security official, told the AFP news agency that the government must overcome past errors and had “no more time to waste” as competition in the region heats up.

Shoebridge said there must be a trimmed-down procurement process, otherwise, it will be a “familiar path that leads to delays, construction troubles, cost blowouts – and at the end, ships that get into service too late with systems that are overtaken by events and technological change”.

Wooing specific electorates with the promise of “continuous naval shipbuilding” cannot be the priority, he said.

“This will just get in the way of the actual priority: reversing the collapse of our navy’s fleet.”