On January 22, health workers in Cameroon began gathering babies and children below five years of age for the first doses of the RTS,S vaccine, which has been developed by pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and PATH, a non-profit health organisation. The vaccine’s designation – RTS,S – refers to the genes of the parasite it was produced from.

Children in Burkina Faso will be next to receive the jab, starting this month. A second vaccine, R21, was approved by the World Health Organization (WHO) in December and is likely to be rolled out in a matter of months. This vaccine is already being used in some African countries, Ghana being the first to approve it last year.

These vaccines have been developed as part of a global push to stamp out malaria, a disease which can be deadly for children and pregnant women. Nearly all of the more than 200 million annual cases in the world occur in African countries.

Here’s all you need to know about the new malaria vaccines:

How do the vaccines work?

Although research for a malaria vaccine has been ongoing since the 1980s and trials started as far back as 2004, the RTS,S vaccine was recommended by the WHO in 2021 as part of a process towards certification. In July 2022, WHO officially approved the vaccine for use. It has a 75 percent efficacy rate.

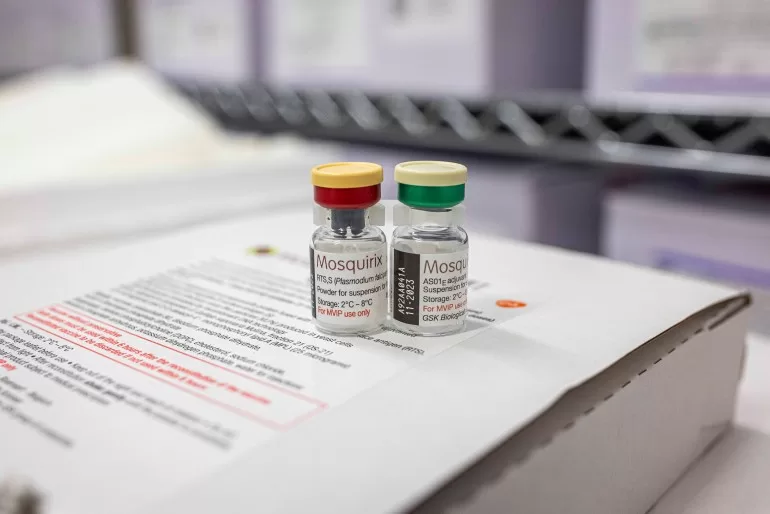

Named Mosquirix, the vaccine is formulated to activate antibodies and target the infectious stage of Plasmodium falciparum, a malaria-causing parasite. This parasite is spread by the female anopheles mosquito when it bites.

In trials carried out between 2009 and 2011 across seven African countries, the RTS,S vaccine prevented infants from developing malaria for at least three years after the first vaccination. Over the four years, malaria cases among children immunised with the vaccine when they were aged between five and 17 months dropped by 39 percent. Among those immunised between six and 12 weeks after birth, malaria cases dropped by 27 percent.

In a pilot programme launched in Ghana, Malawi and Kenya in 2019, the WHO reported that the use of the vaccine had resulted in a 13 percent decline in the number of deaths from malaria among more than two million children monitored.

R21, or Matrix-M, is a second malaria vaccine that was approved by the WHO in December 2023. It was developed by Oxford University and manufactured by Serum Institute of India. In test trials, R21 showed an efficacy rate of 75 percent over 12 months. There are plans to roll out this jab in Africa alongside the RTS,S vaccine in mid-2024.

Wendy Prudhomme O’Meara, a professor at Duke University, told Al Jazeera the main drawback of the Oxford vaccine is that frequent boosters are required.

“Efficacy wanes within a year [and] this makes it very effective for seasonal protection but we hope that as we continue to build the R&D [research and development] pipeline for malaria, we can improve on this,” O’Meara said. “I think the malaria community understands that this is an important first step, but it is not the end of the road.”

How dangerous is malaria?

Severe malaria can cause complications such as organ failure and can result in death. It is the number two cause of toddler deaths in Africa after respiratory illnesses – nearly half a million children die from malaria in African countries every year.

The disease is especially deadly for children because they are less likely to have built up any immunity to it.

Pregnant women in their second and third trimesters are also particularly vulnerable to becoming infected with malaria because their immunity levels are reduced. People visiting high transmission areas from malaria-free zones are vulnerable too because they lack any built-up immunity that comes from living in endemic areas.

Millions of malaria cases are recorded every year around the world. In 2022 alone, some 249 million cases were recorded, with a death toll of 608,000 across 85 countries.

Nearly all – 94 percent – of these were in African countries.

Why are African countries so vulnerable to malaria?

A host of factors including weather patterns, poor sanitation and weak public healthcare systems contribute to the continent carrying nearly all of the world’s malaria burden.

In 2022, nearly all deaths from malaria worldwide were recorded on the continent. Four countries – Nigeria (27 percent), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (12 percent), Uganda (5 percent) and Mozambique (4 percent) – accounted for almost half of all cases.

Malaria thrives in the tropics, where climatic conditions allow the anopheles mosquito to successfully produce malaria parasites in its saliva, which it transmits to humans when it bites them. Waterlogged, damp places are the insect’s favourite breeding ground. During the rainy season, therefore, malaria transmission rates tend to be higher.

Some analysts describe malaria as “a disease of the poor”. Families living in mosquito-infested environments who cannot afford chemically treated mosquito nets or insecticides often bear the brunt of the disease. Treatments for the disease can be expensive. In Mozambique, a 2019 study found that one household will need to spend $3.46 for treatments for an uncomplicated case, but up to $81.08 for treatments for a severe case. The average household income in Mozambique is about $149 per month.

Even without vaccines, malaria could be eliminated if more attention is paid to reducing poverty structures and providing better living environments, O’Meara of Duke University said.

“Malaria was eliminated in the US before modern insecticide-treated nets, before DDT [insecticide] and certainly before artemisinin combination drugs or vaccines,” she said. “Malaria ecology in the US was of course much different than Africa, but still that was achieved by environmental management, bednets [untreated] and by reducing human-mosquito contact through better living conditions. Poor housing construction, open windows and eaves, open drainage systems and poor urban water management contribute significantly to the persistence of malaria.”

Countries in Asia, the Pacific and South America also experience malaria transmission, especially Papua New Guinea. Outside Africa, the disease is also spread by the female anopheles, but it carries Plasmodium vivax, another malaria parasite that can thrive in lower temperatures.

Which African countries have eliminated malaria?

So far, three African countries have successfully rid themselves of malaria: Mauritius (1973), Algeria (2019) and Cape Verde, which was certified malaria-free by the WHO last month after reporting zero transmissions for three consecutive years.

It took a huge effort. Cape Verde, for example, took decades to get the WHO certification. All 10 of its islands were affected by malaria in the 1950s. Using targeted insecticide spraying campaigns, the country reported itself malaria-free in 1967 and again in 1983, only to discover more malaria cases later.

Could malaria be wiped out worldwide?

Eliminating malaria everywhere in the world might be possible, but not with vaccines alone.

Billionaire philanthropist Bill Gates, who commits billions of dollars to malaria research through the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, predicts that malaria could be eradicated by 2040, based on elimination targets at the country level.

The new vaccines are a “momentous achievement” and will provide a huge boost to the global eradication push, but they will not be effective alone, says Krystal Birungi, an entomologist with Target Malaria, an organisation working on developing genetically modified mosquitoes to reduce malaria transmission.

“It is an important addition to the toolbox for the fight against malaria and will save many lives,” Birungi said. “That said, research has shown that no one tool is a silver bullet against malaria and it is still vitally essential to utilise the existing tools, like insecticide sprays, long-lasting insecticide-treated nets and antimalarial drugs, as well as to continue developing new tools like genetically modified mosquitoes and gene drive to fight malaria.”

Many countries already distribute insecticide nets, chemicals and preventive oral solutions in high-risk areas free of charge. However, there are monetary and logistical challenges to carrying out widespread, consistent spraying, with conflict and instability in several countries hindering those measures.

Furthermore, mosquito behaviour is changing. As the world continues to warn because of climate change, studies show that mosquitoes will gain more breeding environments, meaning there could be higher transmission rates for diseases like malaria.

Currently, African countries are trying to tackle the anopheles stephensi, an invasive species originally from South Asia that thrives in urban environments.

“Due to the vector being a mosquito that can fly and doesn’t respect boundaries, we need to achieve malaria elimination everywhere in order to ensure safety for all, even places where malaria has been declared eliminated,” Birungi added.

What happens next with the vaccines?

Burkina Faso – which recorded nearly 12.5 million cases of malaria in 2022 – began its inoculation campaign on February 5, adding the RTS,S to other routine vaccines for children. Some 250,000 children are being immunised in an initial phase because of a limited number of doses.

Children from five months old are eligible for the scheduled four-dose treatment – or five doses for infants and children in high-risk areas.

Liberia, Niger and Sierra Leone will be next to deploy the jab later this year.

There is a very high demand for the vaccines, so supply is likely to fall far short. Only 18 million doses of the RTS,S vaccine are currently available to cover 12 countries through 2025, according to Gavi [full name, organisation, etc?]. It is unclear how many doses are needed or what the shortfall is, however, there are about 207 million children aged below four across the continent. In all, African countries will need some 40 to 60 million malaria doses annually by 2026.

The rollouts may also face social challenges. In the past, rumours that vaccines make women sterile have caused people to shun polio jabs in countries like Nigeria. Bringing the doses to rural and remote areas, as well as finding adequate electricity supply to store them at the required cool temperature, could also prove to be significant hurdles that will have to be overcome.