The bill contains legislation related to various dimensions of personal law. This includes a complete ban on both polygamy and child marriage. It has many significant provisions, such as granting equal property rights to both sons and daughters, abolishing the distinction between legitimate and illegitimate offspring, ensuring equal property rights post-death, and extending these rights to both adoptive and biological children. An important provision of the UCC Bill is the compulsory legal registration of live-in couples. According to the proposed legislation, persons who are in a live-in relationship are required to officially register their partnership within a month of starting it and also acquire parental approval. Registration of such partnerships is obligatory for “any individual residing in Uttarakhand… who is in a live-in relationship outside the state.” The UCC Bill encompasses a comprehensive prohibition on underage marriage and establishes a standardised procedure for divorce. It guarantees equitable rights for women of all religious backgrounds to inherit property that has been passed down through their family. The UCC Bill establishes the age requirement for marriage at 18 for women and 21 for men throughout all communities. Furthermore, it is not permissible to initiate a divorce petition until at least one year has elapsed after the marriage. The UCC Bill recognises that marriage ceremonies may be officiated or entered into by a man and a woman in line with their religious beliefs, practices, and traditional rituals and ceremonies. The enactment of this legislation would signify the realisation of a significant commitment made by the BJP in its 2022 assembly election programme.

The Implications

Nevertheless, as believed by its critics, the implementation of a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) in India encounters several obstacles, such as religious and cultural heterogeneity, political delicacy, legal intricacy, societal consciousness and acceptability, and the absence of governmental determination. Religious organisations, especially those belonging to minority populations, express concern that a UCC may encroach upon their religious liberties and cultural traditions. Political parties often exhibit reluctance to adopt a definitive position on the issue, mostly out of concern about potentially estranging certain segments of the electorate. Legal professionals and intellectuals should collaborate to create a thorough and equitable code that upholds individual rights. The effectiveness of a legislative reform like the implementation of the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) heavily relies on the social consciousness and widespread acceptance of this concept among the general populace. The absence of political determination and agreement has greatly hindered the execution of the Uniform Civil Code (UCC). The discourse around the implementation of a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) in India revolves around the complex job of reconciling the tenets of egalitarianism, fairness, and individual liberty with the intricate tapestry of the nation’s many cultural and religious traditions. In order to establish a UCC, it is necessary to thoroughly analyse these criteria to guarantee a just and comprehensive legal structure. The notion of a common national identity is the foundation of the idea of UCC. During the deliberations in the Constituent Assembly, K.M. Munshi (1948) presented a compelling argument in support of the Uniform Civil Code (UCC).

There are many factors and important factors that still offer serious dangers to our national consolidation, and it is very necessary that the whole of our life, so far as it is restricted to secular spheres, be unified in such a way that, as early as possible, we may be able to say, Well, we are not merely a nation because we say so, but also in effect, by the way we live, by our personal law, we are a strong and consolidated nation.

Since the promulgation of the Indian Constitution, the question of keeping the diversities intact has been laced with the ideas of the federalization process, decentralisation of powers, and protection of personal laws. However, except in a few cases, most of the minorities were brought under the Hindu Marriage Act 1956, which provided further impetus to the demand for the implementation of UCC, as mentioned in Part IV, Article 44 of the Constitution of India. The partition experience and the textual history of the concept of ‘nation’, which was of western origins, kept the scholars at bay from thinking of the application of a UCC. It always haunted their notions of ‘nation’ and ‘national identity’. Bhikhu Parekh (2008) says, “Identity is a product of the conscious and unconscious interaction between the range of alternatives offered by the wider society and our self-understanding.”

The conscious interaction could be reflected in the uniform state legislation, keeping in view the larger human rights perspective against the narrow parochial laws. Taken from the normative side or the group perspective, the question of individual rights and liberties also confronts the group view or community identity here. Peter Dsouza (2015) observes: “Another normative issue on which a position needs to be taken is the tension between individual rights and group rights. While the comfort zone in the argument is to say that we must support both, since they are both valuable, the former on the grounds of individual rights enables the individual to do, be, or become whatever he or she wishes to do, be, or become, and the latter on the grounds that group rights enable community identity to be maintained, which in turn results in the production of a cultural diversity from which all can benefit. The situation on the ground highlights situations where the two sets of rights do not cohabit easily (56). Now that the state has intervened in Hindu laws that are inclusive of other non-Muslim minorities, state intervention in discriminatory personal laws is desirable, as it already has done by banning triple Talaq.

The Indian situation with the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) is very relevant to this scenario. The notion of establishing a shared Indian identity contributes to the concern of minority groups being absorbed into the dominant culture, particularly due to the unfamiliarity of the UCC’s substance. Therefore, minority groups view it as a tool that dominant groups use to incorporate them into the overall national identity, which typically mirrors the identity of the majority. What should be and could be the role of the state in implementing these principles has remained a question from day one. B.R. Ambedkar was also of the view that certain provisions (like reservation, UCC, etc.) of the constitution were temporary in character and would have to go in a staged manner in the ensuing years. Article 36 provides the definition part of the Directive Principles of State Policy. It defines: what is a ‘state’ for directive principles to be followed? The words of the article suggest that the meaning of the state under Article 36 is the same as the meaning of the state under Part III of the Indian Constitution. Article 12 includes the following in the category of a ‘State: the Union Government, the Parliament, the State Governments, the State Legislatures, local authorities, other authorities, or any other body or authority within the territory of India or under the control of the government of India. While the constitution instructs states to endeavour for the execution of Directive Principles, there has been debate around some of the principles, including UCC and the right to work. The implementation of UCC has been challenged on several grounds by political parties and minority groups.

Opposition to the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) in India stems from issues raised by Muslim organisations and political parties over religious liberty, discrimination, historical context, political representation, social conservatism, and gender equality. Some Muslims are concerned that the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) may erode their sense of religious identity and customs, while others are worried that the majority may impose Hindu personal rules. Minority community political groups also object to the UCC in order to preserve their political significance. Certain Muslim groups exhibit resistance towards modifications to traditional Islamic customs and personal laws, while others advocate for the implementation of a shared civil code that promotes equality and harmony. It is important to acknowledge that although there is resistance to a UCC from specific Muslim factions and political organisations, there are also advocates within the Muslim community and other minority communities who endorse the concept of a common civil code as a way to advance equality, secularism, and a cohesive legal structure for all individuals. The discourse around the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) in India is intricate and multidimensional.

Ambedkar was firm in his view that it was permissible for the state to intervene in the religious domain by formulating laws, especially when this intervention promoted the cause of social justice. For him, if this non-interference was conceded, then no progress would be possible. Coming to the question of saving personal law, Ambedkar held, “I should like to say this: if such a saving clause were introduced into the Constitution, it would disable the legislatures in India from enacting any social measures whatsoever. The religious conceptions of this country are so vast that they cover every aspect of life, from birth to death. There is nothing that is not religion, and if personal law is to be saved, I am sure that in personal matters we will come to a standstill. After all, what are we having this liberty for? We are having this liberty in order to reform our social system, which is full of inequities, discrimination, and other things that conflict with our fundamental rights. Having said that, I would also like to point out that all that the state is claiming in this matter is the power to legislate (Ambedkar BR, 1949).

Conclusions

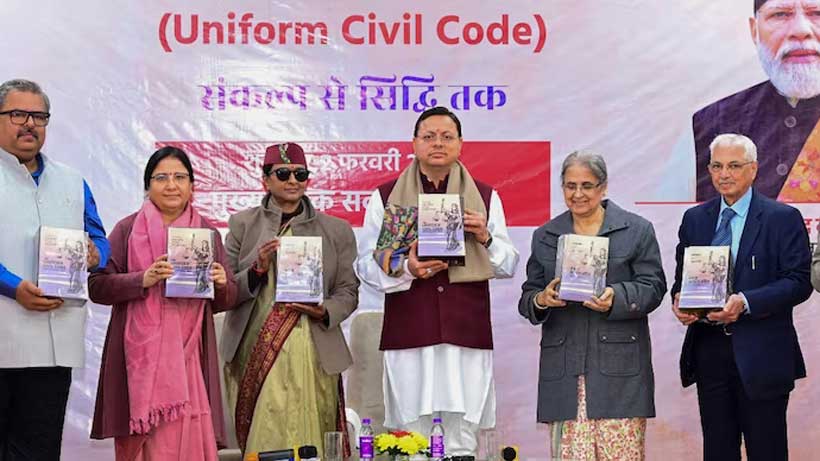

The discourse around a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) is complex, including factors such as religious liberty, cultural variety, and societal customs. Achieving equilibrium between the tenets of a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) and honouring the many religious and cultural customs in India is difficult but not impossible. Implementing a UCC requires meticulous examination, fostering agreement, and taking into account the apprehensions of many populations. A rational and all-inclusive approach should be followed while framing a UCC at the national level. The Uttarakhand experience can help improvise over the drawbacks, if any. The other states are also expected to follow suit and make India more secular, unified, and non-discriminatory, at least when seen from a constitutional and human rights perspective.