More than 90,000 polling booths spread across the nation of 241 million people will open at 8am local time (03:00 GMT).

In addition to the 266 seats in the country’s National Assembly, voters will also elect members to the legislatures of Pakistan’s four provinces. In the National Assembly, a party needs at least 134 seats to secure an outright majority. But parties can also form a coalition to reach the threshold.

Voting will continue until 5pm local time (12:00 GMT), and if the tabulation of results occurs smoothly, the winner could be clear within a few hours.

Yet, analysts are already cautioning that the true test of Pakistan’s tryst with democracy will begin after the elections, when a new government will be confronted by a host of challenges it will inherit, and questions over its very legitimacy.

“While the election results might bring a sense of temporary stability, it is increasingly clear to the public and party leaders alike that long-term sustainability can only be achieved when this cycle of political engineering is broken,” analyst and columnist Danyal Adam Khan said, referring to a widespread sentiment in Pakistan that the election process has been influenced by the country’s powerful military establishment to deny a fair chance to Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party.

Just a day before the election, three bomb blasts, two in southwestern Balochistan and one in Karachi, Sindh, left more than 30 people dead. Over the past year, more than 1,000 people have been killed in violence across the country. Despite assurances from the interim government, fears of internet closure in some areas as well as some election-day violence persist.

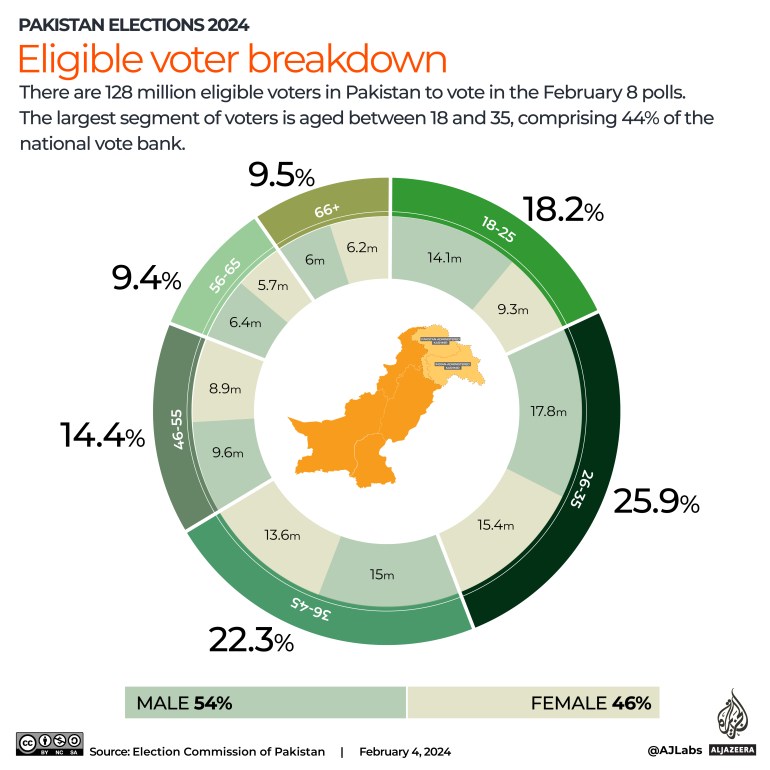

And the economy is in the doldrums, with inflation hovering around 30 percent, 40 percent of the population below the poverty line, a fast-depreciating currency and nearly three-fourths of the population convinced, according to recent polling, that things could get even worse.

Turning tables

Many voters and experts have told Al Jazeera that those challenges have been compounded by attempts to subvert free and fair elections.

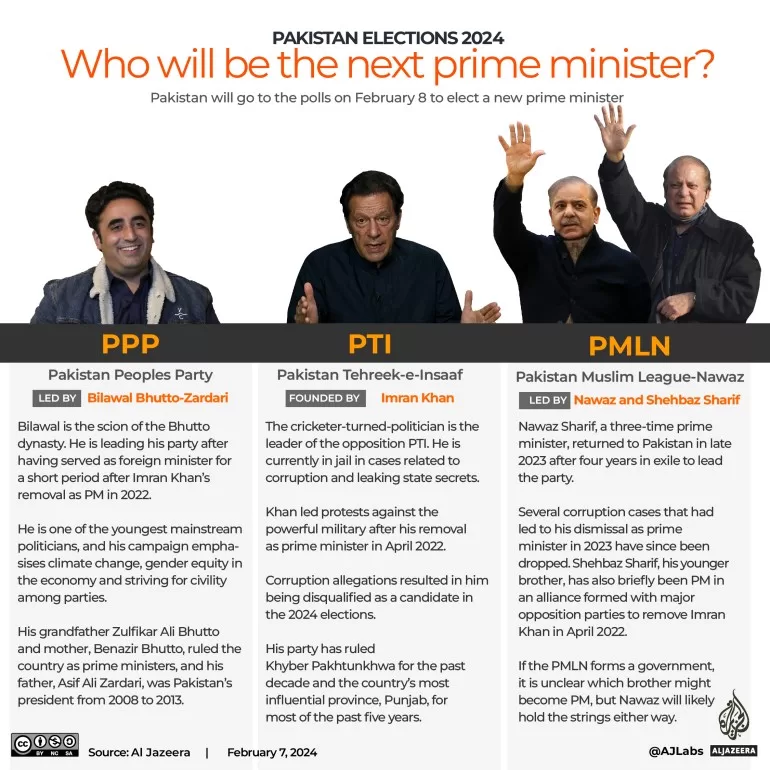

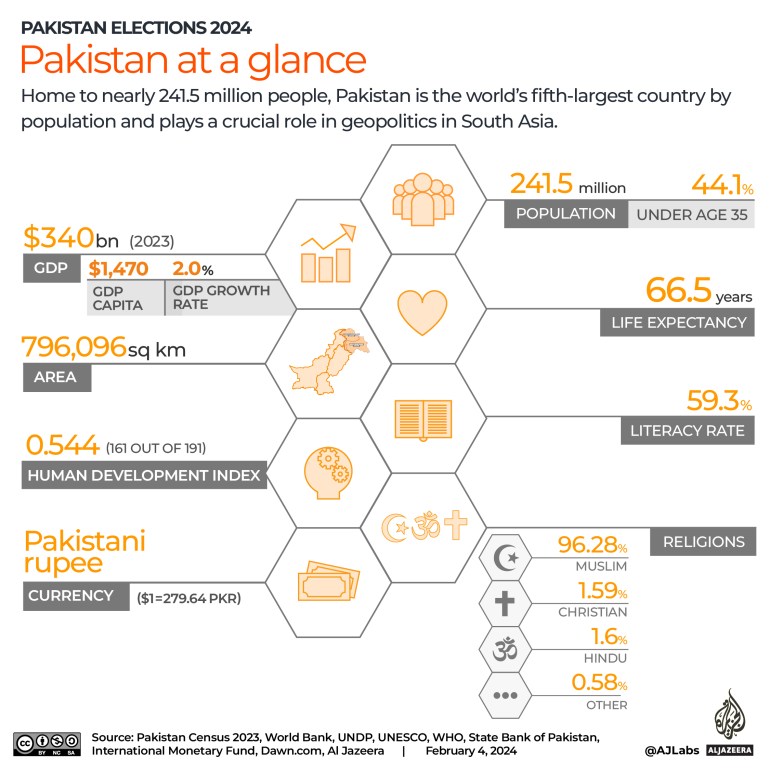

In Thursday’s elections, the top contender is three-time former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, called the “Lion of Punjab” by his supporters. If his Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PMLN) wins the most seats, he could potentially become prime minister for a record fourth time.

However, critics argue that his frontrunner status isn’t due to an inspirational campaign, but rather the machinations of Pakistan’s most powerful entity: the military establishment.

Six years ago, Sharif found himself in their crosshairs, first disqualified from the premiership in 2017 and then jailed on corruption charges for 10 years in 2018, just two weeks before elections.

His removal and the PMLN’s downfall were seemingly orchestrated to pave the way for former cricketer and philanthropist Imran Khan’s rise to power. While their initial honeymoon seemed promising, cracks emerged, and after nearly four years, Khan became the first Pakistani prime minister deposed through a no-confidence vote, continuing a telling trend in the country’s 77-year history: no PM has ever completed their five-year term

Khan’s relationship with the military hit its lowest point on May 9, 2023, when he was briefly arrested for corruption. His party workers and supporters rioted in response, targeting government and military installations.

For a country with more than three decades of direct military rule, where the army as an institution is deeply woven into the social fabric, the state’s response to Khan and the PTI was brutal. Thousands of party workers were arrested, and key leaders were forced to resign. Khan himself faced more than 150 cases, many apparently frivolous. He was eventually jailed last August in a corruption case, leading to his disqualification from the election. Last week, he received multiple convictions in different cases.

However, the biggest blow for the party before the February 8 election came in January, when their iconic “cricket bat” electoral symbol was revoked for violating internal party election rules.

The decision meant that Khan and his party, arguably the most popular in the country according to opinion polls, had no option but to field candidates as independents, each with their own symbol.

The PTI also alleges harassment and even abductions of their candidates, forcing them to cut short their campaigns. The party has complained of restrictions imposed on rallies and media coverage of their plight. These allegations have led experts to consider this one of the most tainted elections in the country’s history.

Sharif’s return in November last year coincided with his rival’s imprisonment, and all his convictions and charges were dropped within weeks. A Supreme Court ban on him from contesting elections was lifted, paving the way for him to lead his party.

With Khan behind bars, Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari, son of former President Asif Ali Zardari and two-time ex-Premier Benazir Bhutto, appears to be the second strongest contender.

As the scion of the Bhutto dynasty and leader of the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), Bhutto-Zardari has campaigned across the country, though the PPP’s core support remains mainly in Sindh.

‘Mockery of democracy’

The crackdown on the PTI has raised questions about the legitimacy of the elections among many analysts.

Danyal Adam Khan, the columnist, said that while the political clampdown is not completely unprecedented, what has transpired before the polls is a “flagrant mockery” of the democratic process.

“Despite the PTI’s own role in promoting a culture of vilifying political opponents, their success at the polls is a matter for the public to decide,” he told Al Jazeera.

Political analyst Benazir Shah acknowledged the history of manipulation in Pakistan’s elections but said that young voters – the country’s largest demographic – had a chance to make their voices heard.

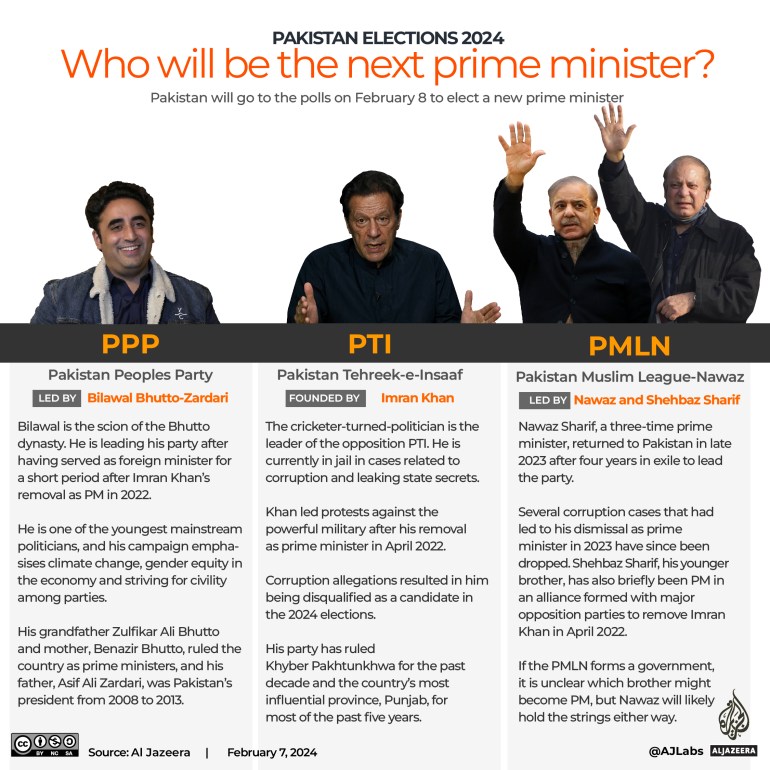

“Out of Pakistan’s 128 million voters, over 45 percent are between the ages of 18 and 35. Historically, they have not contributed a lot in elections, but it is their moment to shine and voice their opinion,” she said.

Pakistan has historically had a relatively low turnout in polls, with only the previous two elections (in 2013 and 2018) witnessing a turnout of more than 50 percent since 1985.

According to election statistics, from 1997 onwards, the voter turnout of those between the ages of 18 and 30 never crossed 40 percent, reaching a high of 37 percent in 2018.

“Despite all the allegations of pre-poll rigging, I am still hoping for a high voter turnout, where the young people come in and vote for the party of their choice,” the Lahore-based Shah said.

‘Hope is at a premium’

Beyond concerns over political persecution, the dire economic situation looms large. Inflation and currency devaluation paint a grim picture.

The country was on the brink of a default last year when in June, then-Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif managed to get a $3bn International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan package, which is set to expire by March.

Addressing the economy will be the next government’s paramount responsibility, said former Prime Minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi. And to do that, he said, the country’s incoming leaders will need credibility.

“Pakistan is still suffering from the political and economic fallout of the manipulated elections in 2018 [when Sharif was effectively forced out of contention]. However, any perception of manipulation in the 2024 elections will be greatly detrimental for the economy,” he told Al Jazeera.

With the latest opinion polls forecasting a win for the PMLN, questions have been raised about whether the results on February 9 can bring some sort of stability in the country’s volatile political landscape.

Danyal Adam Khan said he expects frustration and anger from those feeling disenfranchised but warns against perpetuating a cycle of vengeance.

Analyst Shah also expressed pessimism, fearing further societal polarisation if the PTI feels unfairly represented.

“I feel there will be further divisiveness in the society if one political party and its voters [PTI] will think they have been suppressed and they will feel they were not given fair representation in the polls. This will be quite damaging to the country in the long run,” she added.

Former PM Abbasi said he was sensing a lack of public interest in the elections, reflecting a lack of optimism.

It would be vital, he said, for Pakistan to develop clarity over the relationships between its political, judicial, and military institutions.

“The post-election scenario will be dependent on the ability of the country’s leadership to address all these issues,” the ex-premier said. “Hope for solutions is at a premium, so we can only hope for optimism to prevail.”