As 128 million voters prepare for the February 8 elections, Al Jazeera decodes the key numbers shaping Pakistan.

It is an election that will decide the next government of the world’s fifth-most populous nation. Befittingly, it is also an election of large numbers – very large numbers.

From voters and parties to the economy and more, here’s a guide to Pakistan’s election and to the nation itself, in those numbers.

What’s the election about?

In all, 128 million people registered to vote in the elections to pick 266 representatives on February 8, forming the 16th parliament in a first-past-the-post system.

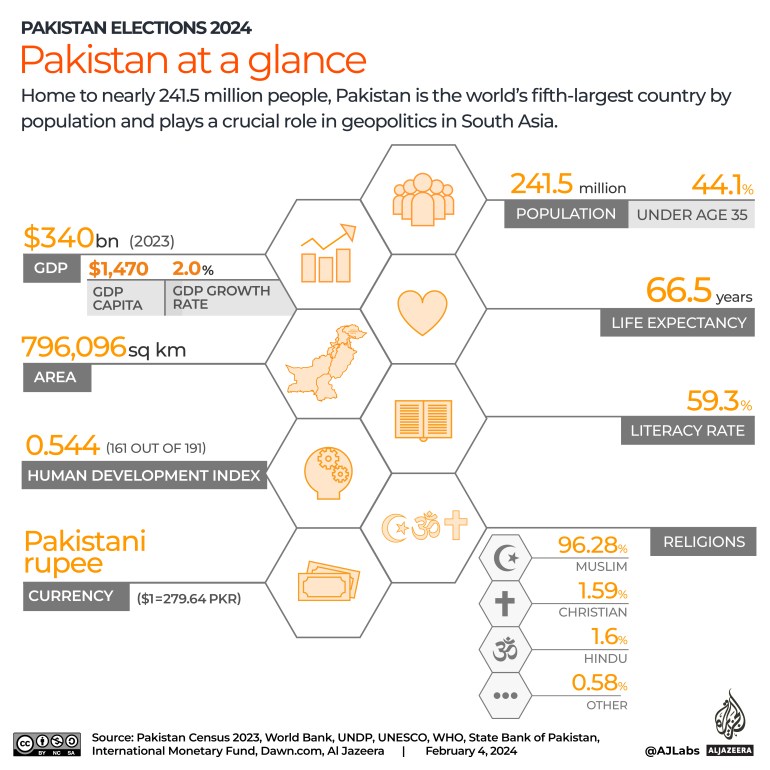

Pakistan is a country with 241 million people, of whom two-thirds are under the age of 30. A citizen becomes eligible to vote at the age of 18.

It is also a vast country, spanning mountainous terrain in its north, multiple deserts and a 990km (615 miles) coastline. On February 8, 90,582 polling stations will service voters who want to cast their ballots.

In the contest are 5,121 candidates. They belong either to Pakistan’s 167 registered political parties or are independents. The Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party of former Prime Minister Imran Khan has been barred from using its election symbol, the cricket bat, so its candidates will also be contesting as independents this time.

Only a little more than half of Pakistan’s electorate voted in the 2018 elections.

With a crackdown against Khan’s party ongoing, it is unclear whether the February 8 elections will see a lower turnout, or a surge in the form of a silent protest vote in favour of PTI-aligned candidates.

How is the country doing?

The elections are taking place amid an ongoing economic crisis, with inflation running at almost 30 percent and a weakening currency, which has shed more than 50 percent of its value against the United States dollar in the last two years.

Meanwhile, the county entered into a nine-month $3bn bailout deal with the International Monetary Fund in July last year, which is set to expire around the same time as a new government will take oath.

In addition to these economic woes, attacks from armed factions have increased in past months adding to the instability of the country.

The struggling economy has allocated 243.6 million rupees ($850,000) for the cost of the elections, which many critics believe has effectively been engineered to keep Khan out of power and instead usher in a leader the military is comfortable with.

Pakistan’s powerful military establishment has ruled the country directly for more than three decades of its independent history.

It is the most powerful institute in the country: 12.5 percent of the government budget goes towards military spending, according to government documents.

The run-up to the poll has seen Khan sentenced to jail in at least three different cases, and former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif – who was previously jailed and then in exile – return and emerge as a leading contender again.

While the economy is teetering, Pakistan is also on edge on the security front, amid heightened tensions with three out of its four neighbours.

Internally, there has been a dramatic surge in violence, while marginalised communities, geographically as well as religiously, have accused the state of mounting persecution.

With a deeply polarised society and uncertainty about the future, many see this election as a referendum on the military’s involvement in politics.

Who are Pakistan’s voters and candidates?

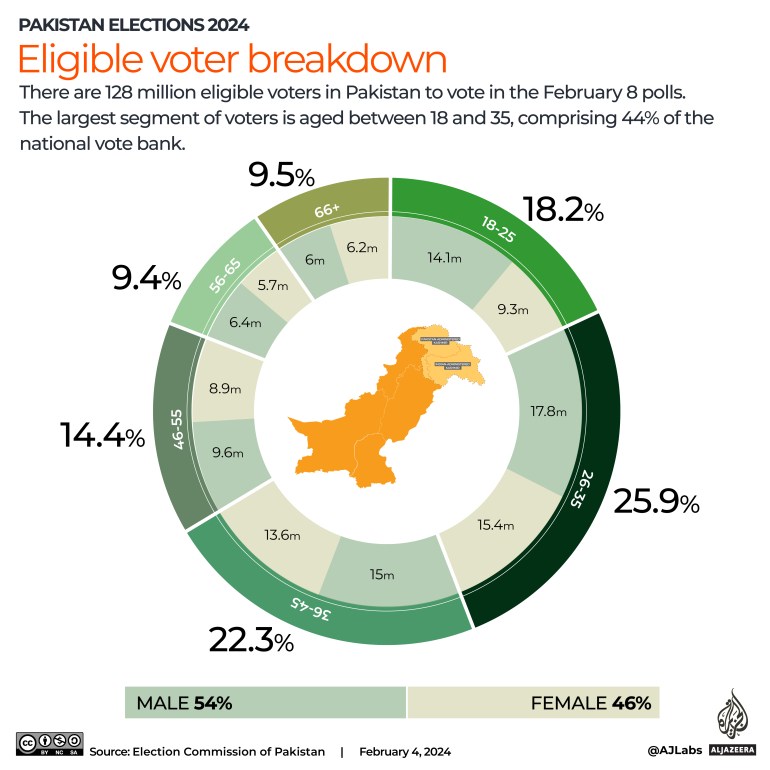

Of the 128 million voters, the largest number – 44 percent – are below the age of 35, making the youth vote critical in these elections.

The second largest group of voters are between the ages of 36 and 45, constituting 22.3 percent of the electorate.

Women form 46 percent (59.3 million) and men 54 percent (69.2 million) of the registered voters.

More than 5,000 candidates are contesting for 266 seats, and among them are 4,806 men, 312 women and two transgender people.