Then there are the two elections in Nevada. The Republican caucuses on Thursday are so “sealed up, bought and paid for” by Trump and his allies,

Nikki Haley says, that she’s not even on the ballot, running instead in the state-run “beauty contest” primary Tuesday in which no delegates are at stake.

Both states are distinct examples of Biden and Trump tilting the playing field. And in some cases the rules changes engineered by one have also benefited the other — like when Democrats’ decision to create a Nevada primary gave Republicans an opening to split the candidate field by also holding an insular, Trump-friendly caucus.

That has stacked the deck against Haley, Phillips and anyone else who has tried or considered running against them. As the race moves away from Iowa and New Hampshire and inches toward Super Tuesday, these arcane rules changes will serve to entrench Biden and Trump even further.

The two would’ve been overwhelming favorites anyway: Majorities of voters in their respective parties tell pollsters they favor Biden and Trump, even as the broader electorate expresses major misgivings about a 2020 rematch between two candidates in their early 80s and late 70s.

And both men had electoral vulnerabilities that could have been exploited, such as concerns over Biden’s age or his handling of conflict in the Middle East, or Trump’s extensive legal peril. But setting up favorable processes has helped insulate them from potential primary headaches.

Both parties have reasons for the changes they’ve made besides boosting Biden and Trump. Democrats want to curtail the role of caucuses, which are less accessible for voters than primary elections. And party activists have long grumbled about the outsize role two overwhelmingly white states, Iowa and New Hampshire, played in the nominating process of a racially diverse party.

Republicans, meanwhile, were unenthusiastic about uprooting their traditions at Democrats’ behest. And in Nevada, they’ve publicly grumbled that the state-run primary next week allows absentee balloting by mail and doesn’t require photo identification to vote, unlike their caucuses.

But a significant factor was Biden’s and Trump’s desire to strengthen their positions.

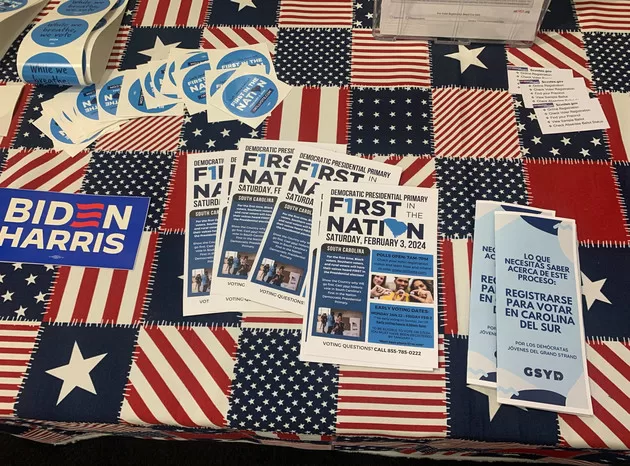

It began with Democrats’ overhaul of their primary calendar, which then reverberated into the GOP race. Biden and the Democratic National Committee picked South Carolina to begin their process — elevating the state that gave the now-president his first victory four years ago after finishing fourth in Iowa, fifth in New Hampshire and a distant second in Nevada.

The Democratic primary in South Carolina is the first to award Democratic delegates — after Biden worked to elevate it to the first spot in his party’s nominating order.

|

Lauren Egan/POLITICO

South Carolina that year was one of Biden’s best states during the competitive stages of the primary, and he carried every one of its 46 counties by performing strongly with its majority-Black primary electorate. (In the 2020 primary exit poll, 56 percent of voters identified as African American.) Moving the state up the calendar provided Biden, who rode Black support to the nomination in 2020, a firewall in the event of a more serious intraparty challenge.

Biden’s move of the South Carolina primary also helped set up an advantage for Trump.

South Carolina doesn’t have partisan registration — any registered voter can participate in either party’s primary. But voters can only choose one primary.

And because the Republican primary is three weeks after the Democrats’, that could hamper Haley’s chances: Anyone who votes in the Democratic primary is ineligible to cast a ballot in the Republican one. Every self-identified independent or voter seeking a Trump alternative who the Biden campaign successfully turns out to vote Saturday is a possible Haley voter taken off the table.

Democrats’ changes to Nevada also helped unwittingly create an opening for Trump.

Nevada is now second in Democrats’ lineup after the 2021 creation of a state-run primary, intended to replace the caucuses conducted by both parties. The law was passed by a Democratic-controlled state legislature and signed by Democratic then-Gov. Steve Sisolak — without the support of Republicans — and set the primary date for the first Tuesday in February.

On the Democratic side, Phillips isn’t even on the primary ballot in Nevada; he didn’t enter the race until after the state’s Oct. 15 filing deadline had passed.

Nevada Republicans elected to spurn the primary, setting their traditional caucuses for two days later. The Republican primary is still happening, just without the state’s 26 delegates at stake.

That’s where the state party’s close ties to Trump come in. A caucus is an event that tends to draw more party activists and insiders, who are very Trump-friendly, than a primary. State GOP chair Michael McDonald

urged supporters to caucus for Trump at a rally in December, despite the presence of other active candidates in the contest. (McDonald has been

indicted for his role as a phony elector following the 2020 election in Nevada, which Trump lost.)

In addition to rejecting the primary, Nevada Republicans set other rules widely seen by other candidates as favoring the former president. For example, they barred any candidate who filed to participate in the primary from also running in the caucuses, which boxed in Trump’s rivals.

That allowed Republicans to turn Democrats’ move to create a Nevada primary into a confusing pair of Republican contests, splitting the candidate field and setting Trump up to dominate the one that actually awards delegates.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis chose to go toe-to-toe with Trump in the caucuses, even as his campaign said the state GOP “changed the rules against the will of the people just to benefit one candidate.” (Since DeSantis has dropped out, his name won’t appear on the caucus ballot on Thursday.)

But Haley and fellow South Carolinian Tim Scott opted instead to run in the primary, trading any chance at delegates for a shot at notching a victory at the ballot box and the media attention that comes from it. Now Haley is the only major active candidate in the primary, giving her victory little meaning or benefit.

Trump, meanwhile, will gobble up the vast majority of delegates. The only other candidate in the caucuses is pastor and businessperson Ryan Binkley.

The last contest of the month is in Michigan — and, again, Democrats’ maneuvering of their primary calendar is closing off another potential avenue for a Haley comeback.

Michigan might not be Trump’s strongest state — he got 37 percent of the vote in a four-candidate race in 2016 — giving Haley a possible opening.

But the Democratic state legislature in Lansing, along with Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, moved up the presidential primary to Feb. 27. That date runs afoul of Republican National Committee rules allowing only four states to vote before March 1: Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada and South Carolina.

So the primary will award less than one-third of Michigan’s delegates. The rest will actually be allocated at a party convention the first weekend of March, before a much more pro-Trump audience. Even an upset victory by Haley in the primary would still likely result in Trump winning most of the state’s delegates.

That leads into Super Tuesday on March 5, when the Trump operation’s state-level machinations have tilted the delegate race in states like California toward him,

as I’ve written previously.

All of those changes, on behalf of Biden and Trump, add up. Beating either man in the primaries would’ve been unlikely. The new rules have made it even more difficult.