Climate justice and democracy are inextricably linked. As climate change impacts have intensified over the years, the ability of democracies to adapt to climate change and mitigate its adverse impacts continues to be tested. Governments in the Global South have had to grapple with extreme weather events whilst also making efforts to create a conducive environment where the fundamental human rights of citizens are protected, and citizens can adequately contribute to socio-economic growth. Reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have continued to raise the alarm that if greenhouse gas emissions are not drastically reduced and curtailed within the agreements of the Paris Agreement, the consequences on communities, nature, and infrastructure will be dire. It will appear however that not much thoughts have been given to the eroding impacts of climate change on the pillars of democracy.

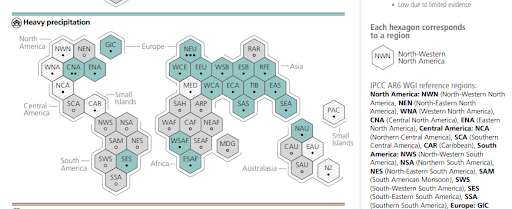

According to the World Meteorological Organization, 2023 was a record year of extreme weather and warmer temperatures across the world. That year also witnessed a record high in sea level rise and a record low in Antarctic sea ice. These statistics continue to worsen as greenhouse gasses increase. The past nine years – 2015 to 2023 – have been the warmest on record and it has been predicted that due to the combined effects of climate change and the warming El Niño weather event, 2024 is likely to be even warmer. According to Prof. Petteri Taalas, the Secretary General of World Meteorological Organization, ‘extreme events such as heatwaves, drought, wildfires, heavy rain and floods will be enhanced in some regions, with major impacts.’ The resultant impact of rising emissions and temperatures are the extreme weather events which have been witnessed in different regions of the world – particularly in developing countries.

Inevitably, grappling with the dual issues of underdevelopment and climate change will put strain on the resiliency and strength of democracies, especially in countries where there is already a high level of political instability. While climate change effects and emergency situations have the possibility to spur regional partnerships in ending conflict and stemming the effects of climate change, these scenarios could also be used as an excuse for authoritarian regimes to curtail democratic freedom. In recent years, countries within the Sahel region (and across Sub-Saharan Africa) have been hit hard by droughts, floods, and inconsistent rainfall. Additionally, a number of these countries have also experienced coups and coup attempts.

The problematic combination of high unemployment rates, ethno-religious intolerance, and political unrest have all played a role in fuelling conflict within the Sahel. The impact of poor governance in further deteriorating the situation should not be downplayed. However, climate change further exacerbates these issues by disrupting the livelihoods of majority of the populace who are reliant on natural resources. Consequently, this has triggered conflict over increasingly scarcer resources. This in turn has also contributed to climate-related security risks.

Evolution of conflicts in the Sahel, 1997-2019

Evidently, the role of climate change as a threat multiplier and threat to democracy cannot be overlooked. It is no coincidence that countries in the Sahel region, particularly Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Chad, which have been impacted by the effects of climate change, have also battled with conflict and a weakened democracy. As climate change impacts worsened, so do the conflicts increase.

When there is a lack of response and infrastructure to fill in the gap and proffer solutions to the climate change threats and issues faced by frontline communities, this leaves vulnerable communities open to non-state actors and armed groups. These groups may try to manipulate the situation to propagate extremist ideologies and carry out terrorist recruitment. In central Mali, researchers have established a connection between child recruitment and scarce rainfall. Dr Farah Hegazi, a researcher in the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) Climate Change and Risk Programme stated that ‘families send their children to armed groups as a form of income. When there is more rainfall, there is noticeably less recruitment into armed groups.’

Additionally, the failure of government-run projects which have been ridden with nepotism and corruption have given a vacuum for non-state actors to take over. For example, Katiba Macina, an armed group that operates from the Inner Niger Delta to the Mauritanian border, has built wells and set up agricultural projects. The frustration of young people towards the government, has seemingly made youth apathetic towards governance and civic participation, and has also made Katiba Macina and other jihadi groups appear more attractive to disenfranchised youth. Thus, this phenomenon has excluded a key demography responsible for helping to shape the future and progress of Mali. Clearly, one of the hallmarks of a healthy democracy is when all citizens can freely participate in governance and enjoy the dividends of democracy.

A similar scenario also plays itself out in Asia where sea levels are rapidly rising and putting communities at risk of coastal and fluvial floods, which are becoming more frequent and severe. Agriculture also faces severe climate risks as crops are being damaged by storms. For example, yearly rice yields in Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam risk being reduced by half due to various climate change impacts.

Across Asia (and the Global South) multiple drivers of inequality and patriarchal structures affect women’s agency around the gendered impacts of climate change. Women often make up a significant portion the workforce in key livelihood sectors, such as; agriculture, fisheries, forestry, energy and manufacturing. However, due to deep rooted inequalities, women who work in these sectors – especially those from marginalized groups – can be particularly vulnerable to climate impacts. For example, women farmers are likelier than men to face water and land insecurity, which constrains their ability to adapt. In other parts of the Global South where there is severe scarcity of water, girls often have to walk long distances across difficult terrain to fetch water. Sometimes, this is at the cost of their education.

Therefore, greater representation and participation of women and girls in the development of climate mitigation and adaptation strategies is essential if the world is to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals on gender equality and transition into a just and sustainable future. It is imperative to ensure that an intersectional lens is used in the formulation and implementation of solutions, so that no one is left behind on the journey to net zero. This means exploring how gender and other demographies intersect with race, class, ethnicity, gender diversity, religion, disability, age, migration status, and other factors. Adopting this approach can inform policymakers and stakeholders on how climate change impacts can worsen inequalities and marginalization. With a holistic set of policies and programmes, the structural and political dynamics that disenfranchise vulnerable groups can be disrupted.

With COP 28 over and 2024 being not just an election year, but the global year of elections and democracy (as more voters than ever in history will head to the polls in at least 64 countries), it is the duty of citizens and stakeholders to hold elected leaders accountable for the promises pledged and treaties signed. The success of the Loss and Damage Fund and Nationally Determined Contributions can only become a reality when there is a continuity of the climate policies and strategies of various countries. Very often, the stance of global leaders on climate policies and strategies may vary during election years – as was the case during the Trump administration when the US withdrew from the Paris Agreement (and subsequently rejoined in the Biden administration). Similarly, in the UK, climate commitments have been backtracked as Rishi Sunak announced a change in the UK’s green policy.

Mounting evidence has shown that the world’s reliance on fossil fuels is no longer an option. Harnessing the numerous possibilities of domestically produced green energy is an avenue that countries must explore if we are to reduce global emissions and achieve net zero. For this to be possible, global leaders must acknowledge that retrogressive changes in climate policy risk derailing the world’s ability to achieve the global climate target. Our leaders must understand that climate change is not just a political issue, it is a human issue that affects us all. Whether we like it or not, the clock is ticking, and the effects of climate change will not wait.

Seun Bakare is the Executive Director at CPA. Temi Alalade is a Program Associate at CPA

Climate Peace Alliance (CPA) is an international non-governmental organisation that works at the intersection of climate justice and violent conflicts. We are committed to addressing climate injustice and conflicts through peaceful and collaborative efforts. Recognising the importance of forging alliances among diverse stakeholders to create harmonious and sustainable communities, we work at the systems level of policy advocacy and grassroots mobilisation for action.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.