Last week, several lawmakers and insiders claimed the taciturn and immensely popular 50-year-old four-star general was dismissed and set to lead Ukraine’s National Security and Defence Council.

President Volodymyr Zelenskyy decided to fire him in early December after Pentagon chief Lloyd Austin visited Kyiv, the Ukrainska Pravda newspaper reported, citing an unnamed source.

But on Monday, Defence Minister Rustem Umerov said: “This is not true.”

Even though the ministry does not hold sway over Zaluzhny, in the case of a potential firing, it would have to submit a “recommendation” for his dismissal to Zelenskyy, Ukraine’s nominal commander-in-chief.

“There’s nothing to talk about. There was no dismissal. I have nothing to add,” Zelenskyy’s spokesperson Serhiy Nikiforov said in televised remarks on Monday.

But several observers have doubts.

“There was an attempt to convince Zaluzhny to switch to another job voluntarily, on his own. The attempt wasn’t very successful, so the matter has been postponed,” Kyiv-based analyst Volodymyr Fesenko told Al Jazeera.

But the dismissal “is a matter of time and circumstances”, he said.

There is “psychological tension” between Zaluzhny and the president, who remains dissatisfied with the failures of last year’s counterattack, Fesenko said.

Popular despite counteroffensive failures

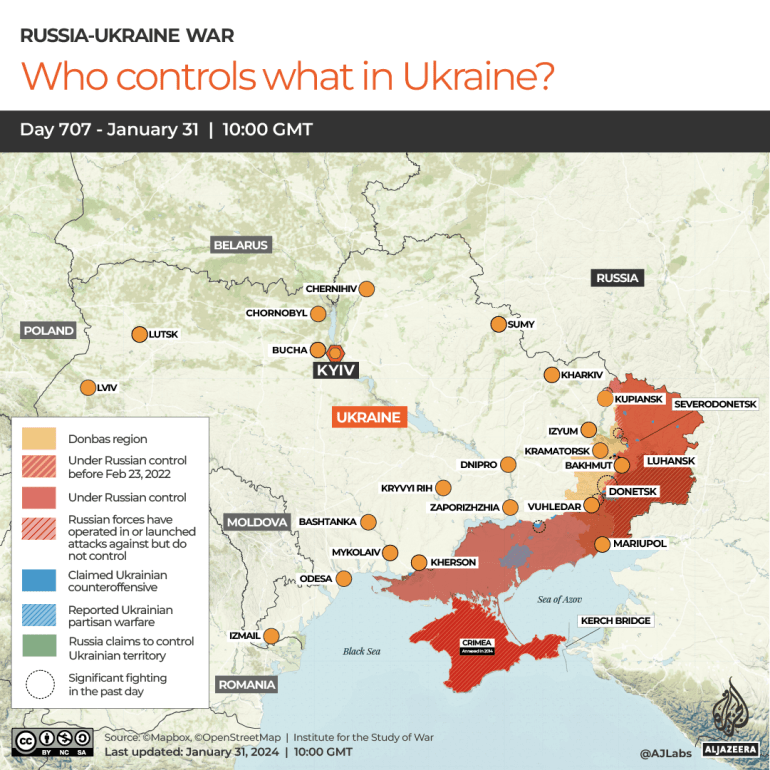

Several counterstrikes in late 2022 liberated almost half of Russia-occupied areas and assured the Ukrainian public that the 2023 summer campaign in the east and south would succeed. But Russia used a lull in hostilities to build multilayer defence installations along the 1,000km-long (621-mile) front line and deployed hundreds of thousands of newly mobilised servicemen to man them.

Zaluzhny’s months-long counterattack morphed into a World War I-like trench war as his forces gained, lost and regained tiny patches of land amid harrowing losses of soldiers and Western-supplied weaponry.

Even the failed mutiny and disbandment of the Wagner mercenary group, which spearheaded Russia’s advance, didn’t help the Ukrainian counterattacks.

The failure was variously blamed on Zaluzhny’s tactical mistakes and delays in the supply of Western weaponry such as fighter jets and missiles.

As Zaluzhny has not come up with a new action plan for 2024, Zelenskyy has occasionally bypassed him in managing the armed forces, Fesenko said.

But Zaluzhny’s authority among the top brass and servicemen remains sky high.

In early 2022, as Ukrainian politicians were adamant that Russian President Vladimir Putin was bluffing and would not dare invade, Zaluzhny, who has headed the armed forces since July 2021, worked hard to prepare.

“In the political sphere, there were different views, but the military with him at the helm tried hard to get ready, and he demonstrated success,” Lieutenant General Ihor Romanenko, former deputy chief of Ukraine’s General Staff, told Al Jazeera.

Once a little-known figure, Zaluzhny rarely speaks to the press and shuns publicity. He is by far the most trusted person in wartime Ukraine.

He is more popular than Zelenskyy – an astronomical 88 percent of Ukrainians trust him, a recent poll found, while 62 percent trust the president.

Seventy-two percent said they are against his dismissal while 2 percent would support it, according to the survey by the Kyiv International Sociology Institute conducted in early December.

But popularity won’t necessarily translate into political success.

Ukraine’s elites and public do not typically view the military and law enforcement agencies as a source of political and presidential material.

Ukraine’s second president, Leonid Kuchma, appointed former intelligence chief Evhen Marchuk as prime minister in 1995 but soon fired him for “trying to form his own political image”.

Another wannabe president, former Interior Minister Yuri Kravchenko, died in 2005 of two gunshots to the head that were officially deemed suicide.

Former intelligence chief Ihor Smeshko and ex-Defence Minister Anatoly Hritsenko formed their own political parties but gained minimal support in their attempts to run for president.

In Ukraine, the army is “not a political institution with a special vision of development like in Latin America”, Kyiv-based analyst Aleksey Kuschch told Al Jazeera.

So should Zaluzhny choose to leave the military for politics, he would be a “good sparring partner” for Zelenskyy but would not be elected president, said Igar Tyshkevich of the Ukrainian Institute for the Future, a think tank in Kyiv.

“But it’s almost guaranteed that he would head one of the largest fractions in the Verkhovna Rada,” Ukraine’s lower house of parliament, Tyshkevich told Al Jazeera.

He dismissed concerns that protests might erupt if Zaluzhny is fired.

Media leaks have named two generals who may replace Zaluzhny.

One is Kyrylo Budanov, a 38-year-old who led small intelligence groups that landed in annexed Crimea before the war and now heads the Main Directorate of Intelligence in the Ministry of Defence.

His agency sent helicopters to aid Ukrainian servicemen fighting in the besieged Azovstal plant in Mariupol in 2022.

It has conducted drone attacks on bombers, warships, air defence systems and military bases deep inside Russia and annexed Crimea.

Budanov’s men have assassinated pro-Russian strongmen and disloyal Ukrainian politicians in separatist-held and Russia-occupied areas.

Another possible replacement for Zaluzhny is Oleksandr Syrsky, a seasoned military veteran who defended Kyiv in early 2022 and kicked Russian forces out of the eastern region of Kharkiv later that year.

If either fills Zaluzhny’s shoes, there is sure to be bitter public feelings towards Zelenskyy, but if an upcoming counteroffensive is successful, they would “dissolve within months”, Tyshkevich said.