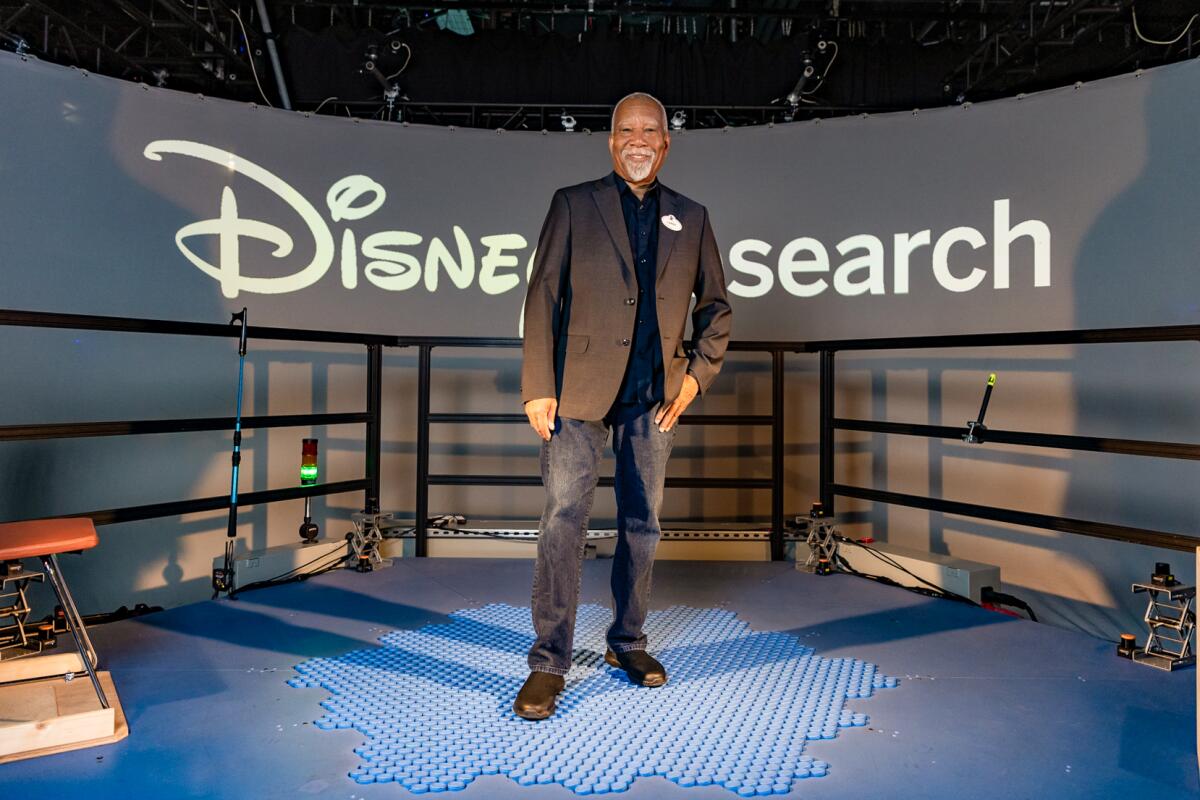

Smoot at 68 is the most accomplished modern inventor at the Walt Disney Co., headquartered in Burbank. Working within Imagineering, the company’s secretive arm devoted to theme park experiences, Smoot creates feats of science that often appear to guests like illusions. With 106 patents throughout his career and counting — Smoot is quick to lean forward and tell me that he is nowhere close to done — his career has been one that proves the applied sciences can be just as much a creative field as a technical one.

(Christian Thom / Disneyland Resort)

His innovative new floor, a creation years in the making, recently was shown to audiences, tucked away inside Imagineering’s Glendale research and development space. Though it does not yet have a designated use in Disney’s theme parks or other experiences, it’s a thing of versatility, and it’s easy to imagine the possibilities.

Think of a treadmill, only one that works with you rather than against you — twisting, turning and moving in the direction of your body — without traditional confines. Disney calls it the HoloTile Floor, and it’s essentially in communication with you, allowing you to move in any direction and never stumble off of its surface. One clear use is virtual reality, as now, inside a headset, one isn’t in danger of strolling into a rail or a couch. But it’s more than a gaming device.

Multiple people can walk — or dance — on Smoot’s HoloTile, allowing for inventive choreography in a stage show, for instance. Anyone, Smoot points out, can “moonwalk” on the HoloTile. Or objects can be directed to roll in the direction of a guest’s choosing, with demonstrated movements recalling some of the magnetic abilities of the Force from the “Star Wars” franchise. Set a chair on the HoloTile and it instantly becomes a ride vehicle, as an operator can spin it or pull it forward. I imagined, for instance, the furniture of “Encanto’s” Casa Madrigal suddenly springing to life once guests were strapped in.

Like many of Smoot’s well-known inventions, it’s not just a technical achievement but a delight. Smoot recently was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame, part of a 2024 class that included, among others, Asad Madni, whose safety and stability breakthroughs are common in cars and have been put to use by NASA, and Andrea Goldsmith, a pioneer in high-speed wireless communications. Smoot’s hall of fame selection is a testament to the power of entertainment, and that designing for large-scale communal spaces such as theme parks can inspire the sort of wonder that can improve lives.

“I know a lot of electrical engineers now, and I ask them how they got started. They say, ‘Oh, I kept taking things apart,’” says Smoot, sitting in a modest office at Disney’s research and development campus. (Just outside his door sits a training pod for robots in development, where Imagineers have been testing bipedal droids that can hop in place, bow their heads and nudge and prod humans as if they are robotic pets.)

“I was a little bit different,” Smoot continues. “I figured out how they worked before I took them apart, and what components may be inside them that I could take out and make my own things. I think that’s part of what causes creativity. Not that I want to see someone else’s thing. I want to see my own thing.”

And when it came to the HoloTile, Smoot wanted to see something from one of his favorite television franchises brought to life. He talks eagerly of “Star Trek,” noting how important it was to him as a child growing up, he says, in poverty in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Brownsville. It was Nichelle Nichols’ communications officer Uhura, Smoot says, who partly inspired his career path. “I was a fan of ‘Star Trek’ partially because of the technology, but because I saw a Black character, Uhura, who did technological things,” Smoot says.

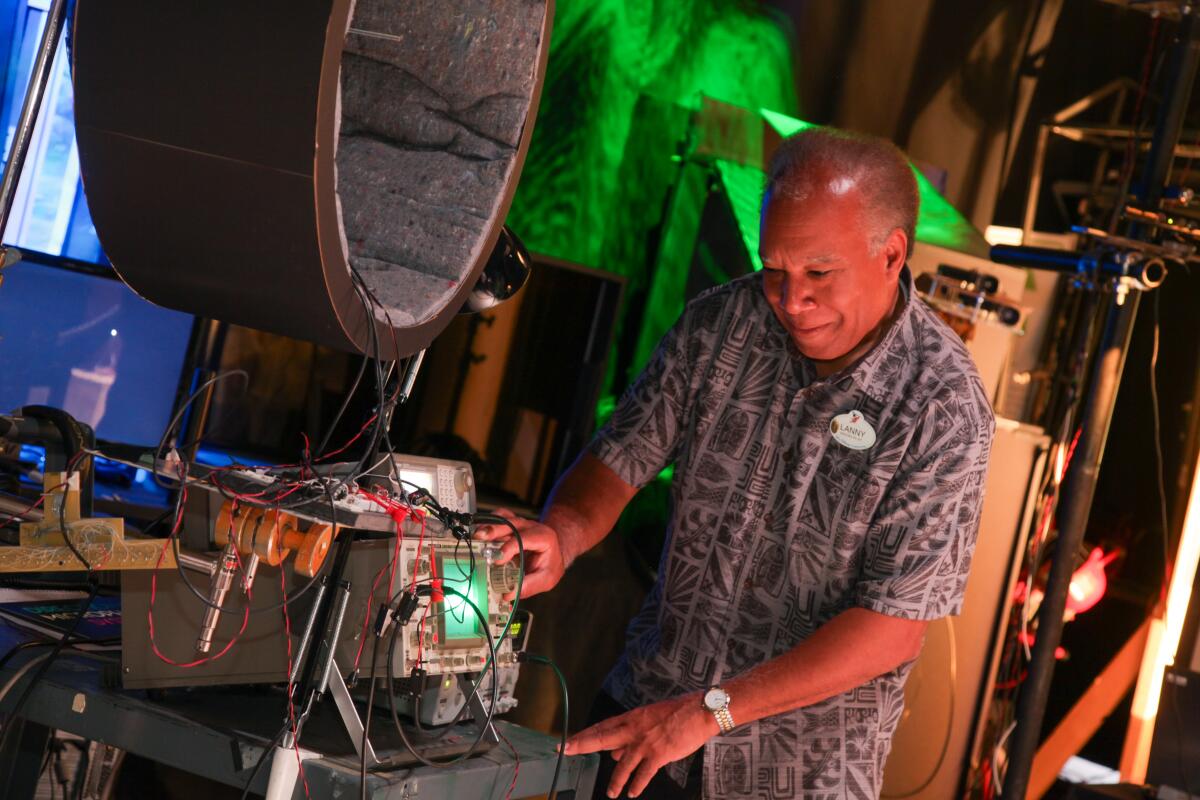

Lanny Smoot joined the Walt Disney Co. in the late 1990s and currently has 106 patents.

(Christian Thom / Disneyland Resort)

His love for “Star Trek” never waned. Smoot says the HoloTile began not so much as a solution to any particular problem Disney needed to solve but as him wondering whether it could be possible to create a “Holodeck,” where in the sci-fi universe real-world settings are brought to life via holograms.

“I knew about the thing called the ‘Holodeck,’ which is where people can walk around forever in a room that’s 24 feet by 24 feet,” Smoot says. “They’re going off to distant mountains and streams. How can that possibly be, right? It must be that the floor of the ‘Holodeck’ has the ability to move people in any direction, to allow them to walk in any direction, to prevent them from bumping into things like the walls of the room or each other. It made me think. How do you have a moving surface that allows you to walk on it forever in any direction? The joke I make is that if you are on it, and someone leaves the room and doesn’t take you off, you will starve to death. That was the spark.”

As it developed, so it did its potential uses.

“He really wanted to solve the ‘Holodeck’ problem,” says Bobby Bristow, who has long worked closely with Smoot at Disney. “He wasn’t quite sure how to get there. It started with multiple iterations — very different technology in the beginning. It wasn’t until we got the version that we have now where we were like, ‘We can also use it to do this.’ We can do all these other things. It’s not just moving people it unlocks but also objects. We’re excited for internal people to tell us what other uses they could have for it.”

It may be some time before guests are able to use or witness Smoot’s HoloTile in a theme park, but plenty of Smoot’s work is scattered around Disney’s locations. Disneyland’s Haunted Mansion, for instance, is home to a seance room, one in which a crystal ball houses the head of Madame Leota as she conjures the spirits shown in the attraction. Madame Leota floats, patiently hovering above a table as she calls forth the apparitions. This was a Smoot trick, added to the Mansion in 2004, and he won’t reveal the secrets of how it works but notes the solution was part engineering feat and part illusion.

Lanny Smoot is credited with finding a way to make Madame Leota’s head float in the Haunted Mansion.

(Joshua Sudock / Disneyland Resort)

Smoot also remade the the portraits in the Mansion’s entry walkway. Here, the imagery flickers between the mortal world and more forbidden realms — ghostly knights, ships, catlike creatures. “The prior changing portraits required a roomful of equipment,” Smoot says. “It was a complex effect. My effect was so much smaller, and it gave the Mansion an instant change during the lightning. As soon as the lightning hits, the portraits change.”

Other Smoot inventions at Disney parks around the world: At Florida’s Epcot, Smoot concocted a former exhibit called “Where’s the Fire?” that challenged guests to uncover hazards by utilizing a flashlight that acted as an X-ray-like device, an installation that sprang from a tool Smoot created that allowed people to see through walls. He also worked on that park’s interactive scavenger hunt, the now-retired “Kim Possible: World Showcase Adventure,” and more recently devised a realistic “Star Wars” lightsaber that simulated the look of an illuminated, retractable blade, which many online patent hunters have compared, in simplified terms, to a sort of reverse tape measure.

The lightsaber was featured in the short-lived but beloved Star Wars: Galactic Starcruiser. Smoot, for his part, is reticent to talk details, preferring to keep his secrets, well, secrets. “It was a fun thing to do,” he simply says of the lightsaber.

Lanny Smoot says a love of “Star Trek” inspired his career.

(Disneyland Resort)

He’s more comfortable instead discussing his career as if it’s a lifelong hobby. Smoot’s journey took him initially to Bell Labs, where he worked on early video teleconferencing tech, before beginning talks with Disney in 1998. The firm at first sought Smoot’s advice on camera mechanization that allowed for on-demand view changes for Florida’s Animal Kingdom park. “The company tried out the panning camera — all good — but it turns out they liked the inventor even more, and I was literally pulled into the Walt Disney Co.,” Smoot says.

He credits his love of invention to his father, and speaks of early science experiments as if they are toys. When he was 5 years old, Smoot says, his father brought home a battery, an electric bell and a lightbulb. “I’m sitting there at the table, and he puts them together and he gets the bell ringing,” Smoot says. “This was like magic. Then he gets the light lit. I say this is poetic, but it’s true. It lit the rest of my career. I was locked into science, mostly electricity.”

Disney, he says, has been such a good fit because he’s constantly amazed at how his technology gets hidden by the company’s staff of artisans and architects.

“I always say my stuff works,” Smoot says. “That I guarantee. It may not be the best-looking, but it works. It’ll get there.”

Now, what to do with a ‘Holodeck’ floor? Smoot and his team teased creations such as an interactive dance floor, but there’s room for more — a restaurant, say, in “Coco’s” Land of the Dead in which we rotate among tables, a “Turning Red” show in which Mei in red panda form can move buildings, an exhibit in Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge in which we can become one with the Force. Reimagine the floor, and there’s no ceiling on the possibilities.