Eighteen months later, Motley’s memory was summoned again, this time by Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson upon her nomination to the Supreme Court.

For the record:

7:20 a.m. April 4, 2022An earlier version of this article misidentified Danielle Holley-Walker’s first name as Nicole. It also said Njeri Mathis Rutledge was an undergraduate classmate of Jackson’s at Harvard University. They attended Harvard Law School together.

The parallels are hardly coincidental. Motley, a path-breaking lawyer and jurist, is a natural inspiration to be shared by Harris, a former prosecutor who became the first Black and South Asian woman to be vice president and Brown, who is poised to be the first Black female justice of the nation’s highest court. The ascension of both to their historic posts is a reflection of the outsize and enduring influence of Motley and a handful of fellow civil rights lawyers like Thurgood Marshall and Charles Hamilton Houston.

“When you see them, you see the generation of Black lawyers before them, many of them who have largely gone unheralded,” said Danielle Holley-Walker, dean of the Howard University School of Law. As members of the first generation to follow the civil rights movement, she said, “we all had very common role models because there were not very many people before us.”

The Senate Judiciary Committee is scheduled to vote on Jackson’s confirmation on Monday and will likely deadlock, although Democrats will still be able to advance her nomination to the full Senate for final approval.

The lawyers most often cited by Jackson, 50, and Harris, 57, were all involved with the landmark Brown vs. Board of Education case, in which the Supreme Court struck down the doctrine of “separate but equal” in public schools. Marshall, the lead lawyer, later became the first Black Supreme Court justice. Houston was Marshall’s mentor and key architect of the strategy to chip away at legalized segregation in the run-up to Brown. Motley, a protege of Marshall’s, was the first Black woman to argue before the Court and was appointed to the federal judiciary in 1966.

The frequent mentions of these legal icons have served Harris and Jackson in multiple ways. Both women point to their role models to explain their own motivations for public service and how they approach their current jobs. The call-outs offer learning opportunities for audiences that don’t know these lawyers, and serve as a kind of shorthand for those that do.

For Jackson, Motley’s legacy has been a recurring motif in the nomination process. In her first speech as President Biden’s nominee, she took pains to note that she was born 49 years to the day after Motley. She discovered that fact in law school when, she later said, “secretly at that point, I was thinking maybe I might want to be a judge.”

Motley’s name came up a dozen times in the Senate Judiciary Committee confirmation hearings, evoked by Jackson and friendly Democratic senators.

Democratic Sen. Richard Blumenthal, eager to tout that Motley was a daughter of his home state of Connecticut, remarked, “She was very predominantly responsible for Brown versus Board of Education. Thurgood Marshall got most of the credit, but she did a lot of the work. Probably sounds familiar to you.”

Motley is indeed less well-known than other civil rights figures, but for the women of Jackson’s generation, she was a star.

“I believe every little Black girl who wants to be a lawyer knew about Constance Baker Motley,” said Njeri Mathis Rutledge, who was friends with Jackson when they were law school students at Harvard University and now teaches law at the South Texas College of Law. “I vividly remember looking up to and admiring her, and feeling like if she could do it, I could do it.”

Even when Motley and her cohort were not mentioned by name, their legacy loomed large in the hearings, including in some of the more antagonistic moments. Republicans used Jackson’s history as a public defender to insinuate she was soft on crime, a charge also levied against Marshall, the last justice to have had substantial experience representing criminal defendants.

And 55 years after Mississippi Sen. James Eastland bluntly asked Marshall, “Are you prejudiced against white people in the South?” Jackson faced similarly provocative questions on race — most notoriously, from Texas Sen. Ted Cruz, about an anti-racist children’s book, “Do you agree with this book that is being taught with kids that the babies are racist?”

When Jackson was repeatedly pressed to describe her judicial philosophy, observers detected the influence of her civil rights predecessors in her answer.

“When she explains how she views the law, it’s very much in this tradition of understanding the tools the law gives you, understanding the facts of the case … coming from a neutral position,” said Holley-Walker, adding that Jackson’s emphasis on the legal fundamentals recalls the Brown vs. Board lawyers who were “serious technicians in the law.”

Harris, meanwhile, refers to her idols as a set of three, repeating it so often it is almost like a mantra: Thurgood Marshall, Charles Hamilton Houston, Constance Baker Motley. They were mentioned in both of her memoirs, and in countless campaign speeches, as her inspiration for studying law.

“It tells me she knows her history — the history of the civil rights movement,” said Tomiko Brown-Nagin, a Harvard Law professor and author of “Civil Rights Queen,” a newly released biography of Motley.

Harris has shown particular reverence for Marshall; she was sworn in as vice president on a Bible that once belonged to him, and displays a bust of the late justice in her ceremonial office.

But generally she speaks of the trio of attorneys who were the “heroes of my youth,” Harris told the Detroit chapter of the NAACP in a 2019 speech. “Those individuals who had the skill to translate the passion from the streets to the courtrooms of our country.”

She casts that admiration as an essential through-line of her biography, especially after she arrived as an undergraduate at Howard University, the historically Black institution where Houston once led the law school and Marshall was a most revered alumnus.

“They were talked about constantly in terms of the legacy of Howard,” said Lita Rosario, a classmate who recruited Harris to join the university debate team. “The symbolism of someone like Thurgood Marshall [was] this is who you can be if you stay. … It’s a journey of excellence and you have to live up to that standard.”

The environment was starkly different when Harris moved on to law school in San Francisco at UC Hastings, which at the time had the reputation of an elite old boys club, and minority law students often faced alienation.

“All of us felt that level of culture shock,” said Diane Matsuda, a law school friend of Harris who is now an attorney in San Francisco. “It was the first time I really felt that racism.”

Shauna Marshall, who taught Maya Harris, the vice president’s younger sibling, at Stanford Law, said the transition was likely especially abrupt for Harris.

“Hailing from Howard, you’re instilled with a sense of you belong everywhere,” said Marshall, who later worked on a pilot anti-recidivism program with Harris, then the San Francisco district attorney. “I am sure those role models and luminaries were really instrumental in [Harris] maintaining her eyes on the prize.”

Their influence on her carried over to her early years as a front-line prosecutor, said Darryl Stallworth, who worked with Harris as newly-minted lawyers in the Alameda County District Attorney’s office.

“We had a number of conversations when we were talking about the legacy and the responsibility of passing the torch — the opportunities we had based on everything our ancestors had done,” said Stallworth, now a criminal defense lawyer in Oakland. He said they shared a belief that the best way to change the criminal justice system was to reform it from the inside.

Harris has often cited those attorneys as part of her decision to become a prosecutor — a move that she said was met with skepticism from her family. None of the three lawyers she often references were prosecutors themselves, but Brown-Nagin said Harris likely got inspiration from their work exposing abuses in the criminal justice system.

Her law enforcement experience later caused friction with some Democratic primary voters, and Harris at times seemed unsure of how to talk about it. She relied on the references to those civil rights figures as a rhetorical device, especially for Black audiences.

“There’s a way in which you have to telegraph that ‘Yes, I am in this position of power. Yes, I have to sometimes make hard trade-offs. But my North Star is still the North Star of my people,’” said Marshall, who is now a law professor at UC Hastings. “That is a great way of conveying it by just naming those people.”

Harris would deliberately name-check the lawyers in front of largely white audiences as well.

“She was trying to lift them out of obscurity a little bit,” said Sean Clegg, a former senior advisor. “A lot of times — always with curiosity and support — a lot of white people found themselves Googling those names. That’s positive. That’s a good thing.”

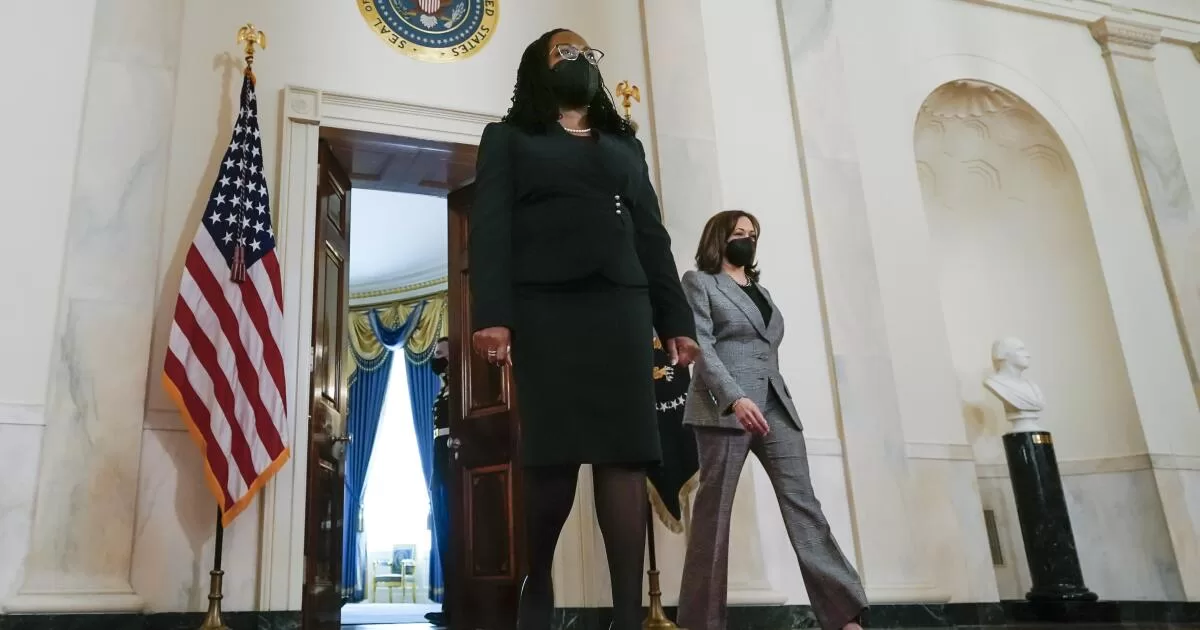

After decades of drawing on the legacy of Black legal trailblazers, Harris is now part of the administration that is set to add a new name to that list of “firsts.” Jackson is expected to be confirmed with votes from the entire Democratic caucus and at least one Republican, Sen. Susan Collins of Maine. The final vote in the Senate holds the possibility of a moment rich in symbolic symmetry: the first Black female vice president presiding as the first Black woman is confirmed to the Supreme Court.

“There’s people like Charles Hamilton Houston and Thurgood Marshall that we’ve looked up to all these years. And now it’s our turn,” said Rosario, Harris’ Howard classmate who is now an entertainment lawyer in Washington.

“Kamala is standing in those shoes,” she added. “Judge Jackson is standing in those shoes.”