The question may be beside the point, since Benji and David scarcely need permission to complain to (and often about) each other. Theirs is a familiar, bickersome buddy-comedy dynamic, with Eisenberg playing the exasperated straight man to Culkin’s volatile post-“Succession” comic fireworks. But Eisenberg, in a major leap forward from his 2022 writing-directing debut, “When You Finish Saving the World,” doesn’t hurl contrived obstacles into his characters’ path or force them into a tearjerking reconciliation. Over a fleet, deceptively light 90 minutes, he grounds the comedy in an exquisite understanding of character, an ear for Chopin and an eye for the loveliness of Polish towns, cities and landscapes. (The cinematographer is Michał Dymek, who filmed last year’s staggeringly beautiful donkey drama, “EO.”)

The story in “A Real Pain,” which was acquired by Searchlight Pictures during the festival, isn’t strictly autobiographical; if it were, it might well lend the title a third meaning. But it has a potent personal dimension nonetheless. One key location that the characters visit, late in the movie, is a house that belonged to members of Eisenberg’s family before World War II. It’s not the kind of detail you’d know to look for beforehand, but think about it afterward and it starts to feel revelatory, giving rise to a sense of loss and longing that reverberates, almost retroactively, across every frame.

Sundance has long been a haven for semiautobiographical stories from up-and-coming filmmakers, particularly those with less firmly established Hollywood roots than Eisenberg. The old adage to “write what you know” can, at worst, give young auteurs license to indulge their most solipsistic instincts; it has also happily yielded some of the festival’s standout entries in recent years, including Lulu Wang’s “The Farewell,” Lee Isaac Chung’s “Minari,” Radha Blank’s “The 40-Year-Old Version” and Celine Song’s “Past Lives.” The tradition, of course, goes back further still; watching the now 40-year-old Eisenberg in “A Real Pain,” I couldn’t help but flash back on the fresher-faced version of him who appeared onscreen in 2005’s “The Squid and the Whale,” Noah Baumbach’s wonderful Sundance-premiered dramedy about his own parents’ divorce.

(Sundance Institute)

This year’s U.S. dramatic competition offers its own semiautobiographical bounty, including two I’m looking forward to catching up with: Sean Wang’s “Dìdi (弟弟),” which won an audience award and an ensemble acting prize, and Laura Chinn’s “Suncoast,” which drew an acting award for its young star, Nico Parker. (“A Real Pain,” meanwhile, won the competition’s Waldo Salt Screenwriting award.) They were joined in that section by “Exhibiting Forgiveness,” an often heavy-handed but forcefully acted drama of intergenerational anguish drawn from the personal experience of its first-time filmmaker, the painter Titus Kaphar.

His alter ego here is a successful artist, Tarrell (André Holland), whose happy home life with his singer-songwriter wife (Andra Day) and their young son stands in stark contrast to the pain of his own upbringing. That trauma, always present, comes flooding to the surface when La’Ron (John Earl Jelks), the father Tarrell hasn’t seen in years, suddenly walks back into his life, reopening a Pandora’s box of memories involving neglect, abuse and alcoholism.

The one who unexpectedly nudges Tarrell toward forgiveness is his mother, Joyce (Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor), whose Christian faith has enabled her to release her own anger toward La’Ron. Watching “Exhibiting Forgiveness” often reminded me of the lessons of my own distant evangelical upbringing: namely, that forgiveness is primarily a release of anger and ill will toward an offender, rather than a commitment to trust or reconcile. Kaphar has a tendency to overstate these and other ideas, including the therapeutic value of art, but his work with his actors is consistently superb: To watch Joyce and Tarrell struggle with their convictions and emotions in one furious argument is to witness Ellis-Taylor and Holland at the peak of their powers. Here, too, a real pain seems to break through the surface of the filmmaking.

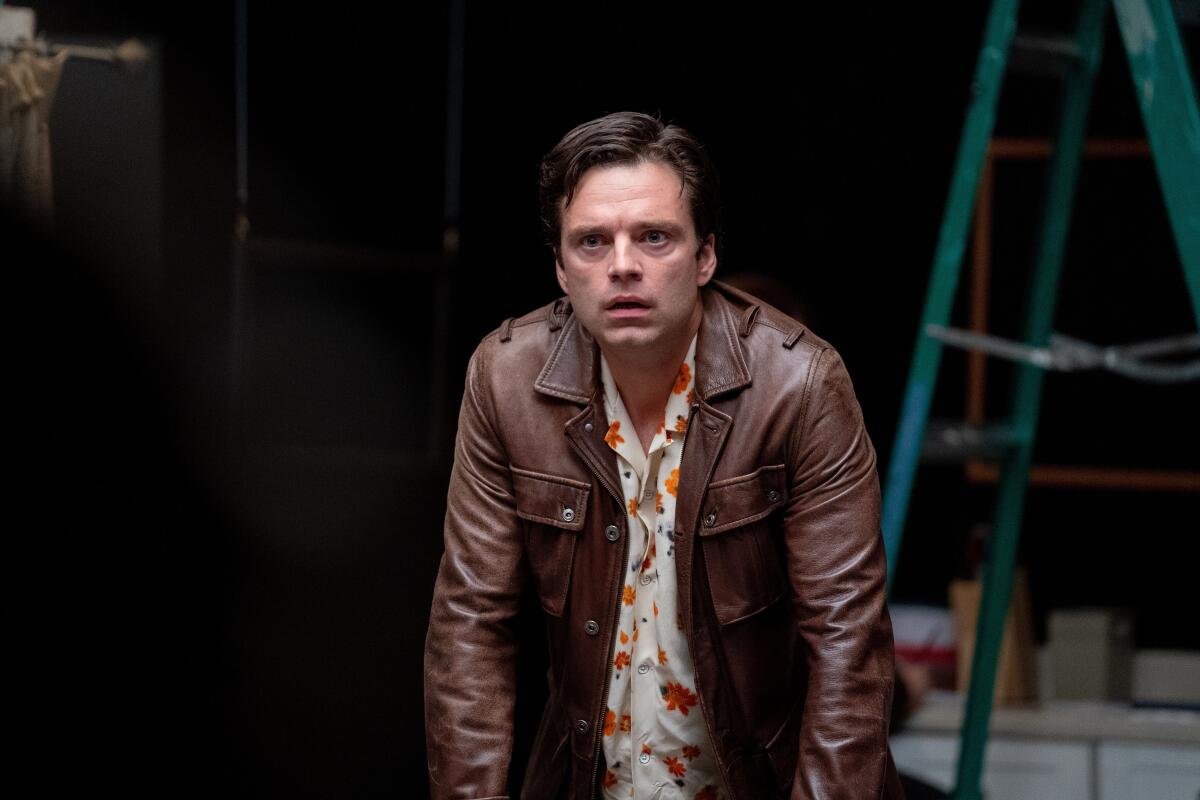

Sebastian Stan in the movie “A Different Man.”

(A24)

But what if that pain isn’t recognized as real by those around us? What if a spectacle of authentic human suffering is obscured by disfiguring layers of flesh — or, in a bitterly ironic twist, concealed by a physical beauty that people assume to be superficial and depthless? These and many other questions arise over the course of Aaron Schimberg’s “A Different Man,” a self-deconstructing meta-pretzel of a dark comedy that premiered in the festival’s high-profile Premieres section. By turns a Woody Allen-style riff on life-art mimicry and a Cronenbergian study in flesh, blood and identity transference, it was by far the most daring and continually surprising movie I saw in Park City, and one I’ll avoid spoiling before you have a chance to see it. (Set to premiere in competition at next month’s Berlin International Film Festival, it will be released by A24 later this year.)

Sebastian Stan plays Edward, an actor with the genetic condition known as neurofibromatosis, visualized here by large, fleshy facial prosthetics. The movie’s inciting twist is the discovery of an experimental procedure that might heal Edward of his disfigurement — a scientific miracle that Schimberg wisely leaves unexplained. What follows is a roundelay of mistaken identities and bewildering coincidences involving Edward 2.0 (now played by Stan in the unobscured flesh), his playwright neighbor (Renate Reinsve of “The Worst Person in the World”) and an insistent third party, Oswald, played by the English actor Adam Pearson, who has neurofibromatosis himself.

Pearson previously worked with Schimberg on 2018’s “Chained for Life,” five years after his memorable screen debut in Jonathan Glazer’s “Under the Skin,” a title that might have worked just as well for “A Different Man.” His arrival in this movie sends it careening wildly (but with just enough control) in multiple provocative directions, nearly all of which end in a question mark. By introducing an actor with a disorder in a movie starring an actor feigning that disorder, is Schimberg’s movie trying to court or preempt its own representational criticism? Does Edward’s transformation reassert — or make a mockery of — the increasingly held notion that only authentically lived experience can entitle an artist to tell a particular story? It’s neither the first nor the last time that question will surface at Sundance, though at present, it’s hard to imagine it being raised in a more deliriously out-there fashion.