Nothing about Ridgeway, in his comfy Ugg slippers, belied the extreme life he’d lived, from being part of the first American team to summit the towering peak of K2 to nearly dying from typhoid while trekking through the jungles of Borneo to experiencing the horrors of a Panamanian prison after a cockamamie get-rich scheme went south.

Ridgeway, 74, a former executive at Patagonia, seems to have carved out a relatively quiet life focused on conservation in the picturesque valley east of Santa Barbara. (Not to say he isn’t active; he trekked 100 miles across East Africa on foot last year.) He exuded calm, warmth and generosity. There was a glint of impish wisdom in his eye. He offered my partner and me tea. A Bernedoodle named Benny doted on him and he returned the affection.

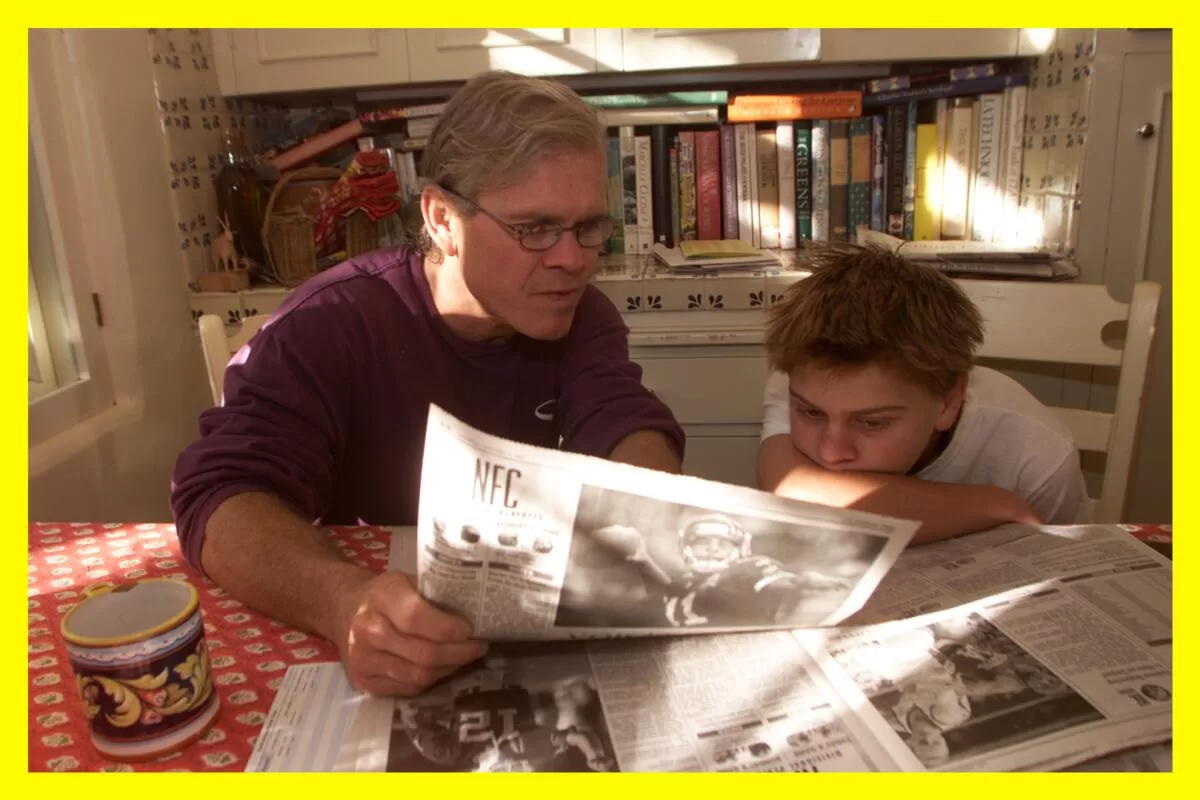

(Bryan Chan / Los Angeles Times)

Small touches in his tidy dwelling hinted at “A Life Lived Wild,” the title of Ridgeway’s most recent book detailing on-the-edge experiences that seem like they belong in a fabled, hardier past. Lithographs of pheasants adorning a wall harked back to his youth when his family raised the birds. A National Geographic issue lay atop a stack of magazines.

Ridgeway, born in Long Beach, moved to rural Orange County between the fifth and sixth grade. The tiny town of Olive had a blacksmith, a one-room bank and a pharmacy with an old-school soda fountain. When his parents split up, he followed his father to the Lake Tahoe area, where he climbed his first mountain and started dreaming of bigger ascents.

His father abandoned him when he was about 15, and he eventually moved back to his childhood stomping grounds. But his idyllic Mayberry was now a construction yard surrounded by tract houses.

“I started going up to the hills around Los Angeles, climbing Mt. Baldy … summer and winter,” he told me last month. “As an escape, as a solace, as a place to find that sense of being in nature that I had as a kid that had imprinted on me.”

I often think about what it means to find a slice of wild in our modern world of at-your-fingertips convenience. And I don’t think it’s a coincidence that outdoor recreation has exploded as unexplored corners across the globe dwindle and technology increasingly frees us from literal legwork.

“Wild” is a concept that contains multitudes. Some might get a whiff of it backpacking in remote regions, while others tap into it while overlanding, growing their own food or shredding slopes. To get to the heart of what it means to be wild in 2024, I sat down with Ridgeway for a chat. Our conversation below was edited for clarity and brevity.

Newsletter

You are reading The Wild newsletter

Sign up to get expert tips on the best of Southern California’s beaches, trails, parks, deserts, forests and mountains in your inbox every Thursday

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

How do you define “wild”? When you chose the title of your book, “Life Lived Wild,” what did that mean to you?

For me, wild refers to the part of nature where our human touch is at minimum. I’ve been fortunate in my own life to have been in a few places in the world where the imprint of human beings was vestigial at best. And I’ve been in a handful of places where there were no signs of our species. And those places are really hard to find. Now, in fact, there may not even be any more of them.

Once I was able to get into what’s probably the most remote corner of the Amazon Basin, not far from where the borders of Venezuela and Brazil and Colombia come together. I was with a few friends climbing at a very remote rock spire that came out of this remote corner of the jungle that was so remote that there were no human beings living in this whole section … And it felt different. And I realized that that’s for me what the definition of wildness was. It also became a baseline that I use for measuring the way I think of wildness.

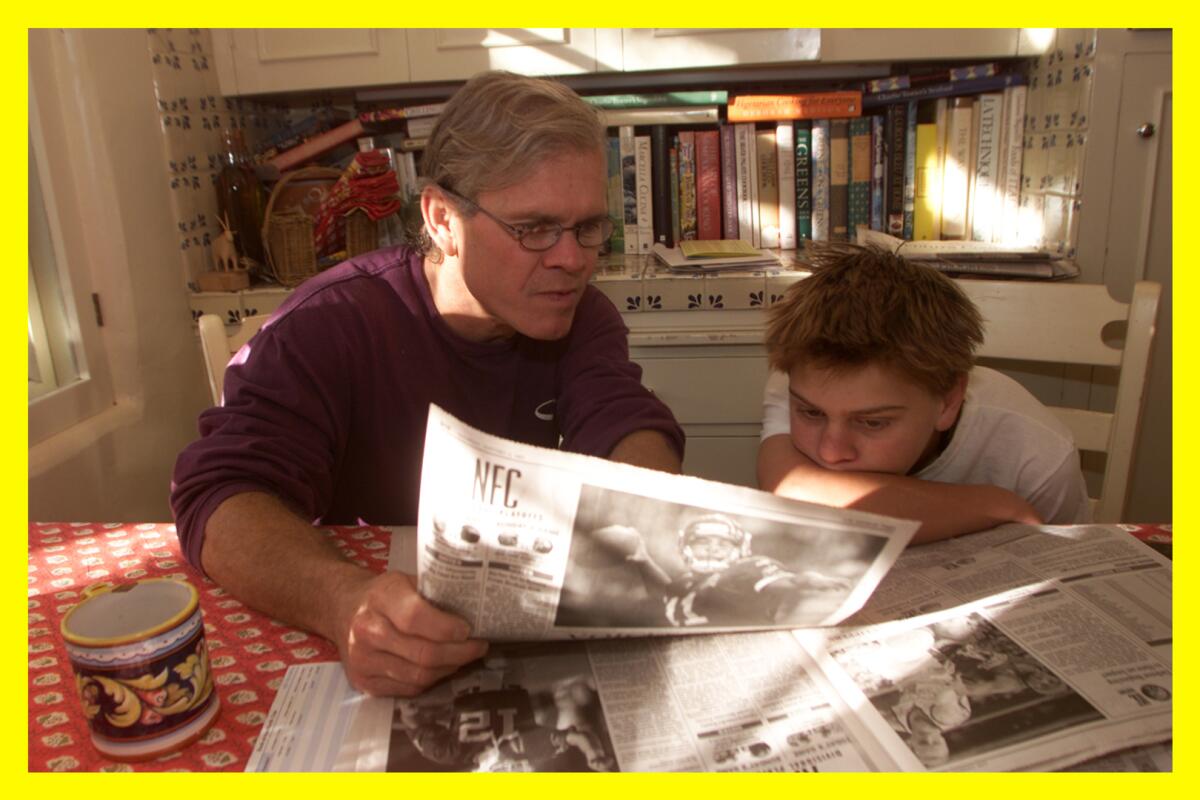

Ridgeway addresses a climate conference in 2013, during his tenure as an executive at Patagonia.

(David Paul Morris / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

And the feeling of being close to the wild, like pre-human activity — is that the same feeling of reaching, for example, the summit of a very high mountain? Are those the same?

It’s something else, but it’s very connected. As the French climber Lionel Terray put it, we were conquistadors of the useless, but the conquistador part was part of it. It was challenging yourself with the goal of applying all the skills that you’ve learned over the years and years of practice to get to the top of a difficult peak. That challenge was a big part of it.

Then the other element for me was the opportunity through mountaineering to be in these really wild places and just be on the — we call them approach marches — to get to those peaks in those years. Back then, you’d have to walk miles and miles just to get to the mountain, and that was usually miles and miles through really wild areas. That was just as much an appeal as trying to pull off the goal of reaching the top. …

Over my life, it became [less] about doing the sports in these wild places [and more about] saving the wild places. That’s been the one line of development in my life. … . And I can see places in my career where I was in transition between one and the other, and a couple of main ones included a trip in my book where we climbed up Kilimanjaro [the highest peak in Africa] from one side and from the summit walked all the way to the Indian Ocean. It was that experience of being on foot and eye-level with critters that put you a few rungs down the food chain. That led to a long introspection about my own relationship and my species’ relationship with our brethren wild creatures.

Climbing and, to some degree, mountaineering has become more popular and I’m curious what you make of that. Does that surprise you?

I have to think back to how the sport seemed to my friends and me in the ‘60s and ‘70s and ‘80s when I was focused on that so much and where we might have seen it going … One thing I do remember is how, in those years, we were all misfits. We were off on the edge of the cultural mainstream. Very few of us had any money at all. And we didn’t really see ourselves as fitting into that part of society that cared about making money.

There’s one climber here in Southern California who famously explained that there is a leisure class on both ends of the social spectrum. And that’s how we saw ourselves. There was nothing leisure about us, yet we were pursuing this sport that had no material contribution to society. That was important to us. That was part of our identity. And to see that part of it gone, where it is now accepted into the culture more … we couldn’t really imagine that happening, but it did. And some of that countercultural part of it is missing for me now.

Are you still getting out? What’s your life like now?

I’m not doing much mountaineering and climbing, but I still walk. And I run every day. I can still run. I got up on that ridge line here yesterday. I was still going and [Benny, the dog] called quits.

In September, Ridgeway returned to Africa to join a foot safari across the Tsavo parks — adapted from a portion of the Kilimanjaro-to-Indian–Ocean trip he completed in the 1990s — to mark the 100th trip of its kind.

[One night on the safari], with the full moon out lighting up our camp, I heard an elephant coming into camp and I looked out the mosquito net of my tent, and I could see this bull [elephant] coming near my tent. I just laid there in my sleeping bag and I watched him as he walked around my tent. And then he stopped — he knew I was there — and he walked right up to my tent. And I was just motionless sitting there looking at him. Then he reached down with his trunk right up near the mosquito net to sniff me and was within four or five feet of my face.

Do you have recommendations for people in SoCal, who want to get a sense of the wild?

If I was a younger person now starting out like I was in the ‘60s and ‘70s, I would be attracted to all the places in our great state of California that, you know, there’s still a lot of corners that aren’t frequented.

I was excited to climb Mt. Whitney for the first time when I was 15 or 16 years old because it was the highest point in California and it was a great adventure for me. Then, going to the lesser-known mountains, I started to realize that’s where it’s really at because there’s nobody there.

There’s still a few things here that I’ve never been able to do. I’ve always wanted to go out to the Mojave in the winter and hike up places like New York Mountain. Not that many people know about New York Mountain. I’ve seen it from the airplane and it looked kind of craggy up on top. Maybe I should try to pull it off this winter.

Rolling Stone called you “the real Indiana Jones” in the 1980s. How did you feel about it? Do you think that’s accurate?

It was amusing. Some of my friends started teasing me about that. And I remember one time I was at this conference in Laguna Beach, some sustainability conference while I was at Patagonia, and Harrison Ford was there. He was on a panel and I was giving a talk. We had met a few times, so after we both talked I was out in the lobby at this event in this hotel, talking to Harrison and this friend of mine comes up and says, “Oh, look, it’s the real Indiana Jones talking to the pretend Indiana Jones.” Harrison wasn’t too amused.

3 things to do

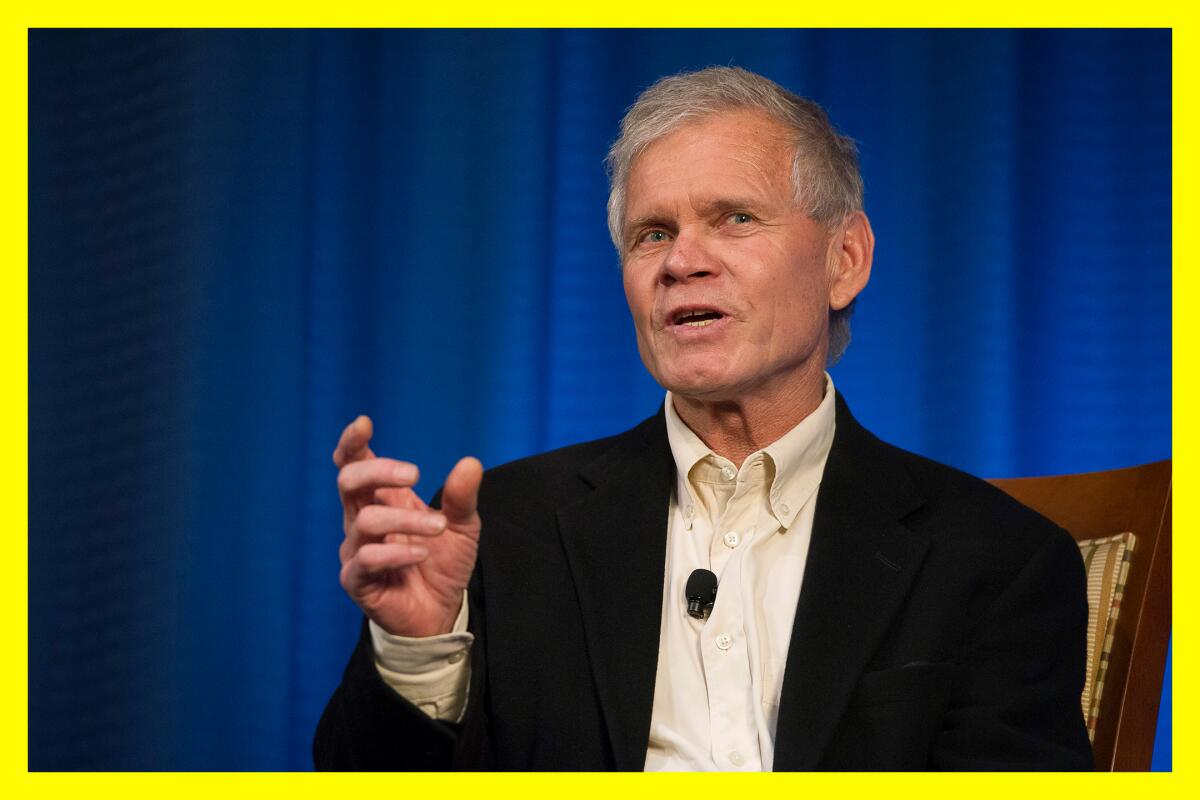

The Eastern Sierra, where Michael Graber began the adventures in alpinism that eventually led him to the world of entertainment.

(Abhinanda Bhattacharyya / Los Angeles Times)

1. Hear how one man combined adventure and cinematography. If you’re hankering for even more insight into how to live wild, you’re in luck. Emmy winner Michael Graber will be giving a talk about how his love of mountain climbing led him to the world of entertainment. After studying philosophy, Graber moved to the Eastern Sierra and began ascending the ranks in alpinism.

In the mid-1970s, he met an Oscar winner who showed him different ropes — those of adventure and documentary filmmaking. Following his passion for climbing and camerawork brought him to Antarctica, Afghanistan, Mt. Everest and other hard-to-access areas. Starting at 6:30 p.m. on Feb. 1, Graber will lead a program, “Capturing the Thrill,” at the Adventurers’ Club of Los Angeles in Lincoln Heights. For more information and to register, visit adventurersclub.org.

The annual Firecracker run, shown here in 2019, will take place in L.A.’s Chinatown on February 24 this year.

(Xinhua via Getty Images)

2. Celebrate the Year of the Dragon with a fiery run. A long-running Lunar New Year run, ride and walk event is set to return to the L.A.‘s Chinatown Plaza next month. On Feb. 24, the 46th annual L.A. Chinatown Firecracker will kick off with 19- and 50-mile bike rides as well as a dog walk open to your four-legged friends. The following day features 5K and 10K walk/runs in addition to a 1K for kiddos.

The event will begin with a literal bang: a traditional lighting of 100,000 firecrackers accompanied by lion dancers. When you’re not in motion (and if you’re over 21), you can enjoy the beer garden. Proceeds will support local elementary schools and nonprofits. Details and registration at firecracker10k.org.

If you’ve ever wanted to visit Sequoia National Park in full winter wonderland mode, recent snowfalls have created opportune conditions — just don’t forget the tire chains.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

3. Visit giant sequoias in the snow. Sequoia National Park — a roughly three-hour drive from Los Angeles — is a favorite weekend getaway for Angelenos looking for a quick escape into nature. Sequoia and adjoining Kings Canyon National Park are best known as sanctuaries for towering giant sequoia trees. (Arguably the most famous resident is General Sherman, the largest tree on earth by volume.) Devastating fires between 2020 and 2021 wiped out roughly 20% of all giant sequoias, which are only found in California. With recent snowfall in the area, it’s an opportune time to see the stately trees in a beautiful winter setting. Families can also enjoy designated snow play areas in the parks for sledding and tubing.

Before you go, make sure to check road and weather conditions, and be prepared to use tire chains. Anticipate below-freezing weather in the sequoia groves, particularly in the mornings, evenings and on cloudy days. More information at nps.gov.

The must-read

Is it time for an “awe walk”? That’s one option for experiencing child-like wonder in this week’s must-read story.

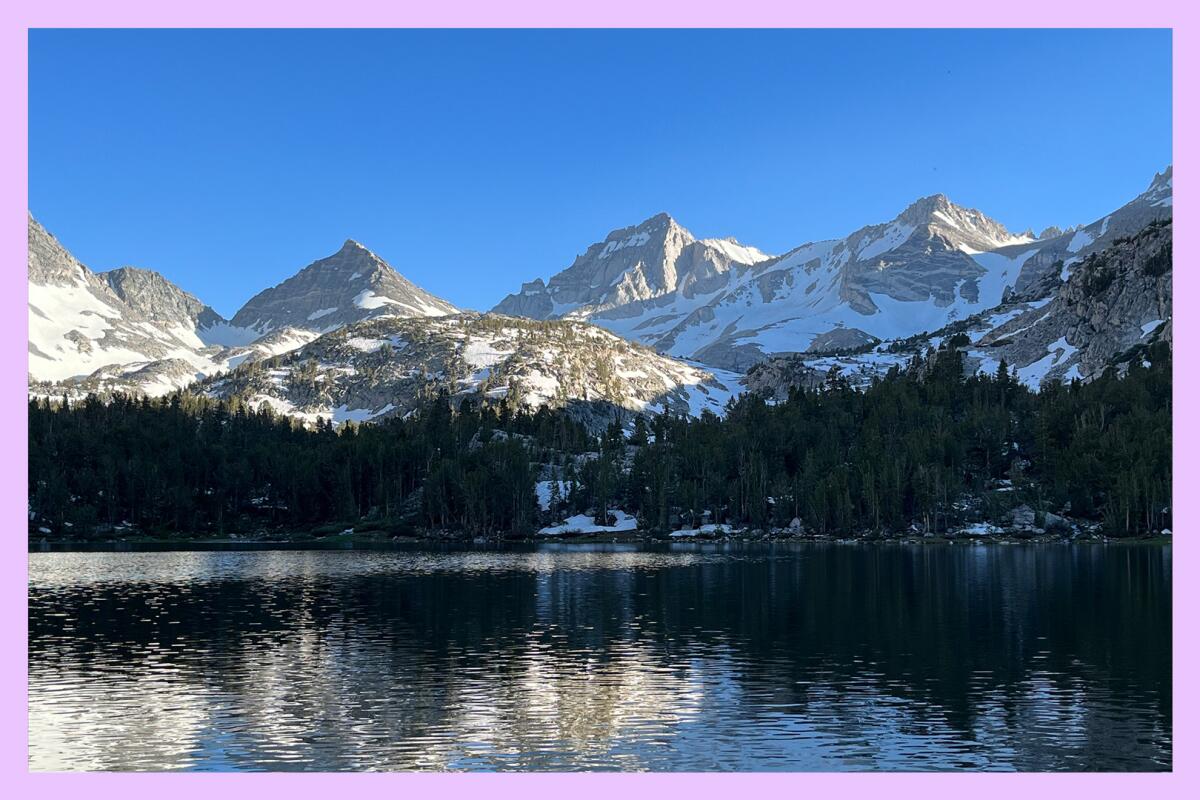

(Changyu Zou / For The Times)

Nature is a no-brainer gateway to awe. There’s even science to back up that tingly feeling when you look up at majestic mountains. Dacher Keltner, a UC Berkeley psychology professor, identified nature as “one of eight wonders of life that often propel people into states of awe,” my colleague Julia Carmel recently reported. (Nature is bosom buddies with spiritual experiences, moral beauty, collective effervescence, life and death and other wonders, according to Keltner.) One of Keltner’s experiments directed people to create self-portraits while looking at either Yosemite Valley or San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf. “The self-portraits from Yosemite consistently had smaller subjects, suggesting that people’s sense of self — or ego — can shrink or even disappear when they’re experiencing awe,” Carmel writes.

Carmel spoke with awe and play experts to uncover the secret of how to go back to a childhood state where falling rain seemed like magic and the tooth fairy might be real. Keltner takes daily “awe walks,” where he slowly takes in the beauty of his surroundings. Often, Carmel writes, he focuses on something small, like a tree, before zooming out.

“You can get to awe quickly, but to really make it rich, it’s got to be part of this broader pursuit of wonders — of life,” he told Carmel.

Farewell

This will be my final edition of The Wild as I embark on a new chapter. This week I received a layoff notice along with more than 100 L.A. Times staffers. It’s been a joy to share this outdoorsy corner of the newspaper with you and go on all kinds of adventures — from hiking with my cat in the hills of L.A. to summiting imposing Mt. Baldy in the snow. Follow me on X at @lila_seidman to see what I hike, climb and write next. I hope to see you on the trail.

Happy adventuring,

P.S.

A soak in the century-old Murrieta Hot Springs — which is reopen to the public as of February 1 — might be just the thing to take the edge off.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Presidential primaries have your stomach in knots? Dry January driving you to snap on a dime? Consider a relaxing soak. On Feb. 1, Murrieta Hot Springs — a forgotten oasis of pools and coveted mud — will open to the public for the first time in nearly 30 years. Once home to a Christian Bible college, a vegetarian commune and mostly Jewish resort, the resort is returning to its roots: water, Times staffer Christopher Reynolds reports. The geothermal pools are ensconced in a palm-shaded compound dotted with historic buildings and establishments to nibble and sip.

For those who’d prefer to keep their soak local, the Times has compiled a list of 10 spas that go beyond Wii Spa and other well-known spots.

For more insider tips on Southern California’s beaches, trails and parks, check out past editions of The Wild. And to view this newsletter in your browser, click here.