Rohtak and New Delhi, India: Dhuli Chand was 102 years old on September 8, 2022, when he led a wedding procession in Rohtak, a district town in the north Indian state of Haryana.

As is customary in north Indian weddings, he sat on a chariot in his wedding finery, wearing garlands of Indian rupee notes, while a band played celebratory music and family members and villagers accompanied him.

But instead of a bride, Chand was on his way to meet government officials.

Chand resorted to the antic to prove to officials that he was not only alive but also lively. A placard he held proclaimed, in the local dialect: “thara foofa zinda hai”, which literally translates to “your uncle is alive”.

Six months prior, his monthly pension was suddenly stopped because he was declared “dead” in government records.

Under Haryana’s Old Age Samman Allowance scheme, people aged 60 years and above, whose income together with that of their spouse doesn’t exceed 300,000 rupees ($3,600) per annum, are eligible for a monthly pension of 2,750 rupees ($33).

In June 2020, the state started using a newly built algorithmic system – the Family Identity Data Repository or the Parivar Pehchan Patra (PPP) database – to determine the eligibility of welfare claimants.

The PPP is an eight-digit unique ID provided to each family in the state and has details of birth and death, marriage, employment, property, and income tax, among other data, of the family members. It maps every family’s demographic and socioeconomic information by linking several government databases to check their eligibility for welfare schemes.

The state said that the PPP created “authentic, verified and reliable data of all families”, and made it mandatory for citizens to access all welfare schemes.

But in practice, the PPP wrongly marked Chand as “dead”, denying him his pension for several months. Worse, the authorities did not change his “dead” status even when he repeatedly met them in person.

“We went to the district offices at least 10 times, out of which five times he [Chand] also accompanied us,” said Naresh, Chand’s grandson. “Even after several attempts to get this anomaly corrected at the government offices, and after filing a grievance complaint on the chief minister’s portal, nothing happened.”

It was only after Chand carried out the parody of a marriage procession and met a local politician that the authorities finally admitted their mistake and released Chand’s pension.

Chand is not an isolated instance of algorithm failure. According to data presented by the government in the state assembly in August last year, it stopped the pensions of 277,115 elderly citizens and 52,479 widows in a span of three years because they were “dead”.

However, several thousands of these beneficiaries were actually alive and had been wrongfully declared dead either due to incorrect data fed into the PPP database or wrong predictions made by the algorithm.

Such anomalies were not restricted to old-age pensions alone. Beneficiaries of disability and widow pensions, and other welfare schemes such as subsidised food, have also been excluded because the PPP algorithm made wrong predictions about their incomes or employment, excluding them from the eligibility criteria.

When people who had been wrongfully erased by the algorithm went to government officials to get the records corrected, they faced red tape. Many were shunted from one office to another, and made to file endless applications to prove the obvious – that they were in fact alive.

The ordeal faced by hundreds of thousands of citizens in getting their data corrected has made PPP one of the most controversial government plans of the Haryana government in recent years. The opposition party has termed it ‘Permanent Pareshani Patra’ (permanent inconvenience document) and promised that it will scrap the programme if it comes to power in the next assembly elections, due in 2024.

The state, however, continues to not just defend but even expand the programme. Sofia Dahiya, secretary of the Citizen Resources Information Department that handles the functioning of PPP, in September 2022 told Al Jazeera: “PPP was easing and improving the delivery of services to the right beneficiaries and preventing leakages through the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning. The interlinking of different databases was done to get an integrated database which was the ‘single source of truth’.”

India spends roughly 13 percent of its gross domestic product, or close to $256bn, on providing welfare benefits to about half the country’s population. Worried that such benefits were being usurped by ineligible claimants, the federal and several state governments have increasingly relied on technology to eliminate welfare fraud.

In the past few years, at least half a dozen states have adopted algorithmic systems to predict the eligibility of citizens for welfare schemes. Over the past year Al Jazeera, in partnership with the Pulitzer Center’s Artificial Intelligence (AI) Accountability Network, investigated the use and impact of such welfare algorithms.

Profiling families

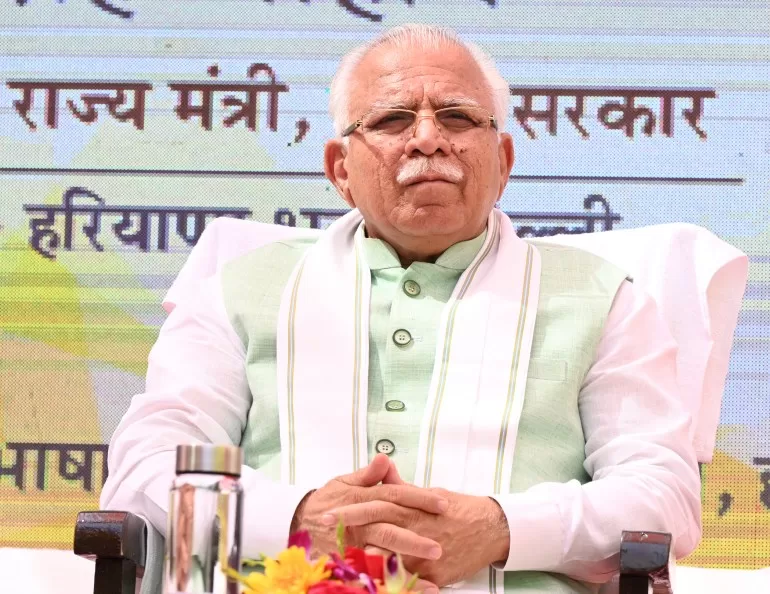

Haryana Chief Minister Manohar Lal Khattar launched the PPP programme in July 2019 and a year later made it mandatory for all welfare benefits.

In the absence of privacy laws, the opposition parties contested the move to gather the personal data of citizens for building out the PPP. The government argued that it allowed “proactive” delivery of welfare without the claimants having to show any documents or needing a field verification. In September 2021, it gave legal sanction to the programme by passing the Haryana Parivar Pehchan Act.

Within a year, however, massive problems with the PPP data started cropping up. After Chand’s ‘wedding procession’ stunt hit the headlines, thousands of poor thronged the district offices of the social welfare department, complaining about their exclusion from the schemes. The public outcry forced the government to launch grievance redressal camps across the state to review PPP data.

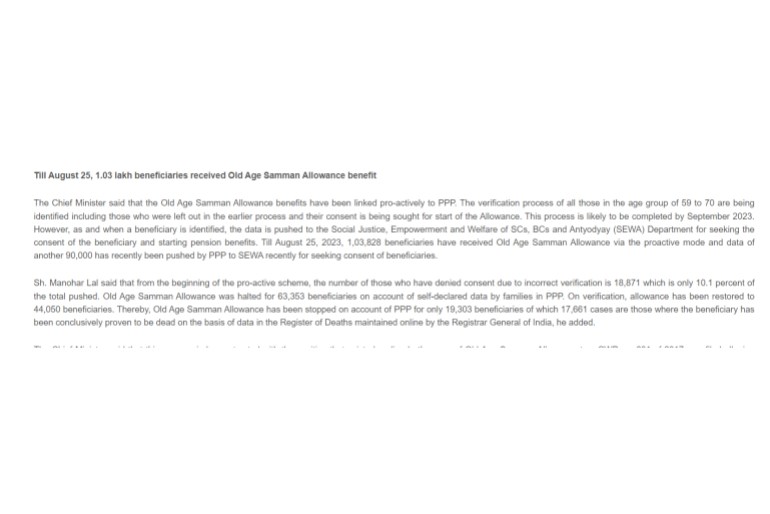

On August 29, 2023, Chief Minister Khattar admitted that out of the total 63,353 beneficiaries whose old-age pensions were halted based on PPP data, 44,050 (or 70 percent) were later found to be eligible. Though Khattar claimed the government had corrected most of the erroneous records and restored the benefits of the wrongfully excluded, media reports suggest that errors still persist.

Algorithmic black box

The government did not respond to Al Jazeera’s Right To Information (RTI) applications seeking information on the design and functioning of the database to ascertain what led to the errors in the PPP database.

A few publicly available government documents, however, provide a peek into the workings of the programme.

To build the database, the government first collected demographic and identity data of the families, including their Aadhaar numbers, the biometric-based unique identity number assigned to every Indian citizen, their age proof, bank accounts, and tax identification numbers through data-entry operators at the village level.

A centralised electronic system then used Aadhaar-based authentication to match the identities of citizens in other government databases such as birth and death registries, land and property records, government employee databases, electricity consumption, and income tax return databases, among others, to build their comprehensive socioeconomic profiles.

This data was then used to “electronically” verify the annual income, age and other eligibility conditions of the applicants. Where electronic verification was not possible due to the unavailability of data, physical field verification was carried out. In cases where the physical verification did not pan out, the family income is derived by “logic-based artificial intelligence [AI].”

The chief minister’s office and the departments administering the PPP and the old-age pension schemes did not respond to Al Jazeera’s queries asking about the logic, formula and source code used by the AI. Neither did it clarify if the errors in the PPP were a result of wrong data entry or incorrect predictions by the AI. The government has also not responded to Dhuli Chand’s RTI query asking the authorities to explain why PPP had marked him as “dead.”

Khattar told the state Assembly that families could contest the income verification carried out by the PPP through “designated online mechanisms”.

But even the families whose data was eventually corrected told Al Jazeera that the process of grappling with an unresponsive official mechanism was onerous and time-consuming.

Death by data

Ram Chander and his wife Ompati, both 60, are residents of Chhichhrana village in Haryana. In March 2022, the couple found out that their old-age pension, which had started only six months ago, had been stopped as they were declared dead in the PPP database.

Ram Chander filed multiple complaints with various government offices but to no avail. That May, he submitted to government officials a notary-signed affidavit saying he and his wife were alive and that their pension be restarted.

In July 2022, the PPP database corrected their status to “Alive” but that error continued in another government database. The local data entry operator accepted their request of “Mark as alive” and that was finally approved after they presented themselves at the office of the Additional Deputy Commissioner (ADC) who heads the implementation of PPP at the district level. The duo’s pension restarted some six months after they had been cut off.

“I have been continuously visiting the office of the ADC since March 2022,” Chander told Al Jazeera in September 2022. “They told me that the mistake had been corrected. Then I visited the local data-entry operator and found out that my status was still ‘dead’, and so I again went to the ADC office. This kept happening every time.”

Al Jazeera met several other families in Haryana who had been denied their pensions due to errors in PPP.

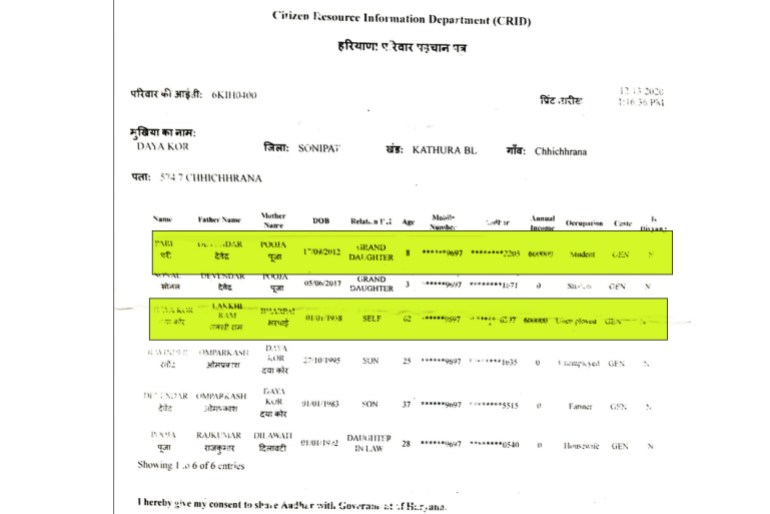

Daya Kor, 64, lives with her family of two sons, a daughter-in-law and two grandchildren. After her husband Omprakash’s death in 1996, she started receiving the monthly widow pension of the state. Widowed women currently receive 2,750 rupees ($33) every month under the scheme. But Kor’s pension was stopped in March 2022. As per PPP records, she and her granddaughter were earning an annual income of 600,000 rupees ($7,200) each. Her granddaughter was just nine years old.

Kor’s family told Al Jazeera that the only earning member in the family was her elder son Devendar, 37, who worked as a bus driver for a private school – earning around 7,000 rupees ($84) per month – and also has a side job as a part-time farmer.

“If the family income was over 12 lakh rupees, why would we need the 2,500 rupees pension?” he asked.

Daya Kor’s pension was finally restarted, but her family cannot forget the ordeal it went through in the process.

“For the correction in PPP, I was told at the ADC office to get an income certificate,” Devendar said. “But to get the income certificate, I am being asked for my PPP. I do not understand how to deal with this.”

(Part 1 of the series revealed how an opaque and unaccountable algorithmic system deprived several thousand poor of their rightful subsidised food.)

Tapasya is a member of The Reporters’ Collective; Kumar Sambhav was the Pulitzer Center’s 2022 AI accountability fellow and is India research lead with Princeton University’s Digital Witness Lab; and Divij Joshi is a doctoral researcher at the Faculty of Laws, University College London.