“If you’re interested in raising money, you certainly want to go to the San Joaquin Valley for water,” said Tom Birmingham, the former general manager of Westlands Water District, the state’s largest irrigator. “But if you’re interested in winning the election of votes, I hate to say it, but in statewide races, San Joaquin is almost irrelevant.”

None of the top four candidates has a fleshed-out water platform.

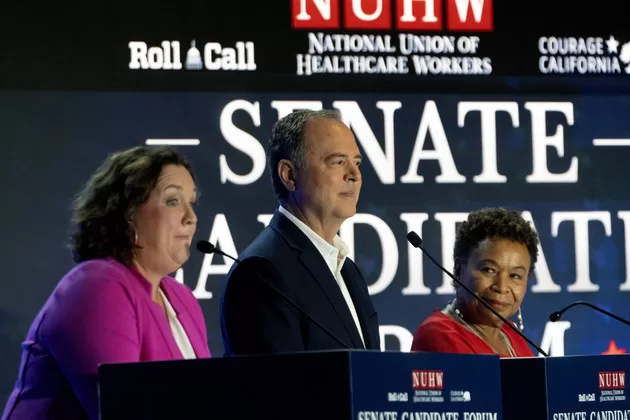

The only mention of water on Rep. Adam Schiff‘s campaign website is his work to restore the Los Angeles River. Rep. Katie Porter’s platform highlights her response to an oil spill off Huntington Beach. Rep. Barbara Lee‘s focuses on her efforts to rid drinking water of pollutants in disadvantaged communities. And former Dodger and Republican candidate Steve Garvey’s website doesn’t mention water at all.

In drought-prone California, water is synonymous with fights between Republican agricultural interests from the geographic center of the state and Democratic environmentalists from the urban coastal centers. Cities need less water overall than farms, meaning they’re less vulnerable to big fluctuations in supplies.

The upshot, for candidates’ political calculus, is a fight they’ve judged they can safely dodge: Cities don’t care, and rural areas don’t count.

“They have only things to lose by articulating it, for the most part,” said Jay Lund, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at UC Davis.

Water could be an opportunity for the candidates to differentiate themselves before voters, especially because the Democrats share so many similar policy priorities. With Schiff currently

leading in polls for the March primary, Porter and Lee are in a tight race with Garvey for second place, which would let them advance to the general election in the fall in the state’s top-two primary system.

The Delta

The most daylight between the candidates so far on water is their positions on the Delta Conveyance Project, a decades-old proposal to pump more supplies from Northern California to Southern California’s cities and farms. Environmentalists, fishing groups and many local lawmakers have fought the project, but Gov. Gavin Newsom is pushing it forward,

saying it would help stabilize water supplies in an era of weather whiplash.

Lee told POLITICO in a statement that she was supportive of the plan, adding that “we must ensure this initiative is done correctly and with environmental justice top of mind.” Schiff said he needed more time to talk with all sides. Porter did not respond to questions.

And Garvey, in a short interview with POLITICO, said someone brought the project up to him at a recent stop near San Francisco. He said he believed in sharing water but was concerned about a price hike in water bills.

Dianne Feinstein, water queen

The biggest contrast overall on the subject is between the Democrats and the late Sen. Dianne Feinstein. Despite her urban pedigree as a former mayor of San Francisco, she

prioritized the Central Valley, working with its Republican House members on bills that changed the state’s arcane water-pumping rules to send more to the parched valley.

Feinstein was close to Birmingham, who managed Westlands Water District, a 1,000-square-mile patch of the arid Central Valley that produces much of the nation’s — and world’s — almond supply. He attributes part of Feinstein’s interest in water to the politics of her time: a Republican had beat her in the 1990 race for governor, and she correctly calculated that support from the Central Valley could carry her in the statewide race for senator in 1992.

Now, with so much of California’s coast swinging left, the math doesn’t favor the Valley.

“I’m not sure that the Valley will have the influence that it historically had,” said Birmingham. “That doesn’t mean that the candidates ignore the Valley.”

All three candidates have attended fundraisers in the Valley. Sarah Woolf, a Valley grower and water-management consultant, said she decided to support Schiff after attending his event because he showed interest in learning about the issues.

But a political action committee she’s part of decided against backing anyone — for now — because they didn’t get any detailed commitment on water policy, Woolf said.

They also didn’t make a detailed ask, she acknowledged. That’s because many farmers feel less urgency to reach out.

Who’ll be the next water champion?

“When you look at the history of the two senators in California, we typically have had a senator that looks to a very large constituency group and does engage with agriculture, and another senator that is more urban-centric,” Woolf said. “I think Sen. [Alex] Padilla has done an excellent job at engaging with the broader California… and probably is going to be our bigger champion on water issues.”

If two Democrats advance to the general election to fill the late Sen. Dianne Feinstein’s seat, water will likely become a more relevant dividing line.

|

Richard Vogel/AP

Schiff appears to have developed the most detailed play on water. In an emailed statement he listed four top priorities: “Updating our aging and broken water infrastructure, diversifying the state’s water supplies by investing in new and emerging technologies, making sure we capture far more of the water during wet years and use it to recharge our underground aquifers, and insuring clean drinking water for all.”

Porter’s campaign has touted her interest in agriculture and background growing up on a farm in Iowa. And Lee has experience with farming groups because of her activism around nutrition and healthy food.

If Schiff and Garvey move forward to the November runoff, it’s doubtful the Democrat will feel any pressure to elaborate any further, given the conservative lean of voters for whom water is a priority.

But if two Democrats advance, water will likely become a more relevant dividing line.

“It’s unavoidable at that point,” said Dave Puglia, the president of the Western Growers Association and a former Republican campaign manager. “You’re gonna get flushed out on it one way or another, so you might as well move proactively in and claim your space.”

Lara Korte contributed reporting.

Garvey, Schiff, Porter and Lee will answer questions about their policy positions during their first California Senate debate from 6 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. PST Monday in Los Angeles. It will be

livestreamed on POLITICO.