Since the invasion of Ukraine, he has seen his homeland as a villainous state bound to follow the path of Nazi Germany, a country with no future and one he wanted nothing to do with.

But even in Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital and his adopted home, Russia kept haunting him. His passport and language identify him as a citizen of an aggressor state – someone who preferred to leave than confront the government. He has also been seen as someone who did not react when Russia was becoming the country it is now.

“I understand perfectly well the general hatred for Russians and for everything Russian. I accept and understand it because what Russia is doing is wrong,” Kosgorov told Al Jazeera. “Every time I want to say that it’s difficult for the Russians who left, something inside me protests, because Ukrainians have it more difficult than us.”

According to estimates, up to one million out of some 144 million Russians left the country in 2022 and 2023 in what has been the largest brain drain since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In a new study, based on several rounds of interviews with close to 10,000 Russian political exiles, Russian researchers Ivetta Sergeeva and Emil Kamalov found that 49 percent of respondents felt strong guilt for the war, while 59 percent felt strongly responsible for it.

As the research suggests, most Russians left because of their opposition to the war in Ukraine and the ever-present narratives that portrayed Russia as a noble country fighting against Ukrainian “fascists”. They also expected further army mobilisation drives, further internal repressions, and a potential economic crisis.

Many decided to settle in countries from the former Soviet bloc, which continue having favourable regulations for Russians to live and work. Countries like Georgia, Armenia and Kazakhstan have already felt the economic and demographic effects of the mass influx of Russians, including rising prices. To many locals, it also brought back memories of Russia’s colonial past.

But as the study suggests, fleeing Russia was not enough to escape its long shadow, as Kosgorov has found out.

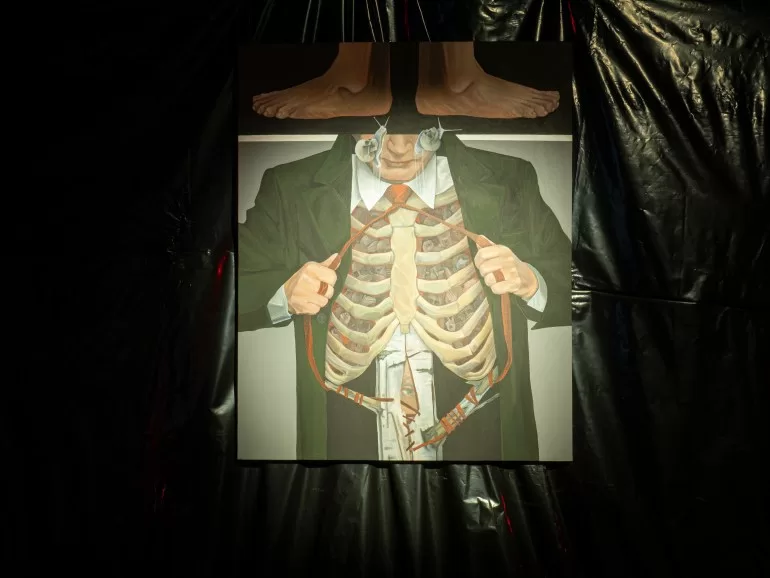

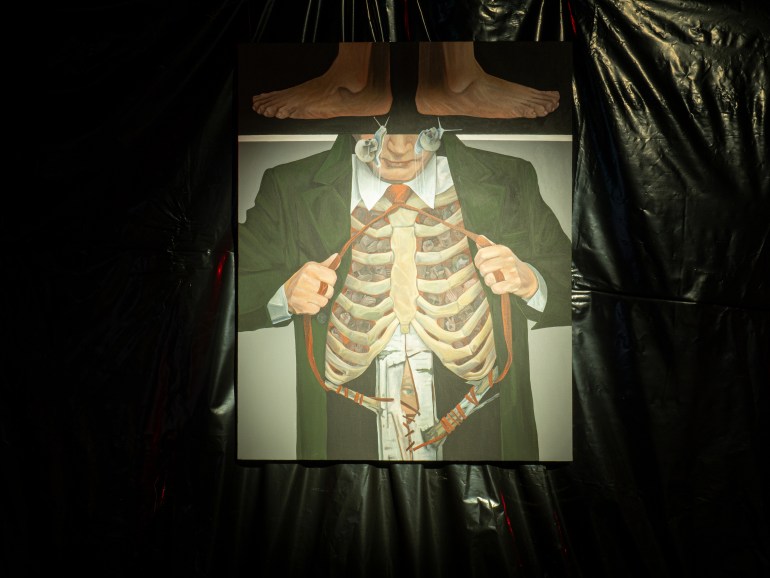

After a few months in Tbilisi, he opened UGallery, a bar with an art space where he hosts antiwar-themed exhibitions and organises fundraisers for Ukraine. But he has struggled to find peace.

“I no longer have a country, I no longer have a homeland,” Kosgorov said. “This is a trivial, simple thing. But what I want is to feel the ground under my feet, and to understand what tomorrow will bring.”

He donates his revenues to NGOs supporting Ukrainian refugees and has gathered a large community of like-minded people, but he knows that not everyone in Georgia welcomes the Russian arrivals; anti-Russian messages can be found graffitied on walls all around Tbilisi.

But Kosgorov does not complain, because he does not feel he has a right to. He does acknowledge, however, that some of the criticism Russian exiles receive abroad is ill-founded.

One of the arguments that he often hears is that they should all return home and dethrone President Vladimir Putin in a mass revolution.

“If you look at the history, peaceful protests seldom brought autocracies down, contrary to military coups. Putin will not disappear from the simple fact that all these migrants who had left go back to Russia and stage a protest. Russia would simply have more political prisoners,” Kosgorov said.

Sergey, a 40-year-old from Moscow who requested to withhold his full name, also feels guilty and hopeless at times. He left Russia in October 2022 with the help of his friends, who lent him money for a plane ticket to Yerevan, Armenia’s capital.

“I certainly feel personal responsibility for what is going on. Russia has turned into a machine for destroying people’s lives. Both abroad and inside the country,” Sergey said. “And this did not happen overnight on February 24 [2022].”

He managed to keep his job and now works remotely from Yerevan while feeling that nothing in his life is certain. What helps him deal with his emotional state is writing letters to Russian political prisoners he knew back in Moscow.

“There are people who are worse off than me, who were imprisoned unfairly based on trumped-up charges,” he said. “Everyone is depressed. I don’t know how many Russian exiles are on antidepressants, but I am. There is an understanding that there are no clear prospects for us and that we must take each day as it comes.”

According to Margarita Zavadskaya, a Finland-based political scientist who researches Russian political exiles, the latest wave of migration from Russia differs from previous instances in that it is more politicised. People trust each other more and form stronger communities, they are not afraid to speak up, and they get involved in activism, she said, which helps them regain dignity and a sense of purpose.

“People feel depressed. They feel guilt, shame, sometimes anger. And they are trying to find themselves and reinvent themselves in the new circumstances,” she told Al Jazeera. “The irony of the situation is that the guilt is being felt by those who are against the regime and understand the scale of the tragedy.”

Unlike previous migration waves, the new voluntary exiles are also more privileged, if not financially, then when it comes to resources they have at their disposal – knowledge, education, and creativity. They can survive and thrive outside of Russia, she said, and are also unlikely to go back home.

When asked if they would like to return to Russia, both Evgeniy Kosgorov and Sergey took time to reply. Their answers were similar. They might return one day when the war is over, if and when Russia pays reparations to Ukraine, and when Putin’s administration is gone. Neither believes any of these events will happen in the foreseeable future.