It was hardly the first time I’d heard that terrifying, guttural rumble of tectonic plates colliding or felt the ground heave and roll under my feet. I was born and raised in Los Angeles, so unlike friends and neighbors who migrated from elsewhere, there was no mistaking that primal sensation for the sound of an approaching train or passing semi. Earthquakes are nature, in all her power, reminding us that we are utterly insignificant.

But even in L.A. terms, the 1994 quake was no ordinary temblor.

The sound of an entire city abruptly rearranging itself atop a thrust fault was deafening, so much that it obscured the din of my bathroom mirror shattering, windows breaking and the kitchen cupboard violently belching its contents onto the hard tile floor.

(Los Angeles Times)

But my bare feet certainly felt the shards of ceramic coffee cups and the slippery surface of scattered CD cases as I ran for cover. Back then, we were instructed to take shelter under a door frame, so I choose the front door.

Outside my apartment in Los Feliz, utility poles swayed as if they were drunk. Sparks flew as the cable lines arced and popped, generating the last bit of DWP-generated light I’d see before the power went out, rendering the city pitch-black aside from fires and flashing sirens. It was déjà vu all over again — no matter that L.A.’s previous terrifying disaster had been man-made.

The riots following the Rodney King verdict were a mere 18 months behind us, and the fear of a city on the edge of total destruction still hung in the air. It also felt like no coincidence that the quake struck on the day we were meant to celebrate Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday.

Though many of the buildings and streets that were damaged in the riots had been restored, or at least cleaned up, the conditions that triggered the uprising were still in play: systemic racism, police brutality, obscene displays of wealth within blocks of generational poverty. It was as if a higher power was reminding us that it would take a lot more than construction crews to fix what was broken.

Adding to a sense of instability and danger that permeated the city even before the shaking began, the Southland had been rocked by record-breaking violent crime. L.A. County experienced an astounding 2,589 killings in 1992. For context, that’s nearly four times as many as 2023’s 651. The era felt something akin to end times, minus the horsemen and locusts.

But earthquakes were part of life for native and longtime Angelenos. My mom’s side of the family runs three generations deep here, and they all had their traumatizing quake stories. My grandmother often spoke about the 1933 Long Beach quake (magnitude 6.4). My parents’ Big One was the 1971 Sylmar quake (6.6).

(It’s sobering to note that California has yet to experience the real Big One. The quake that slammed Fukushima, Japan, in 2011 had a magnitude of 9.0.)

As for me, earthquake preparedness drills were simply part of my education from the L.A. Unified School District. Leaning how to drop and cover was as regionally specific to SoCal schools as were “smog alert holidays,” joyous occasions when the ozone levels hit such dangerously high levels that classes were canceled.

L.A. City Council members take cover under desks during a 1993 earthquake preparedness drill.

(Axel Koester / For The Times)

I was in my 20s by the time the Northridge fault erupted, so I should have known to have a pair of shoes at the foot of my lumpy futon and a flashlight with fresh batteries on the nightstand (a.k.a. a plastic milk crate). But no. When the temblor erupted, I did just about everything wrong, including fumbling barefoot in the dark.

What I could see were the walls distorting as the four-unit, 1940s building swayed back and forth. I can still hear the pop and crack of the plaster and wood.

Later, when the sun came up, I found that my refrigerator had tottered from the wall to the middle of the small kitchen, and my clunky, pre-flat-screen TV had flown halfway across the room from its bookshelf perch before being yanked backward by its electric cord and thrown into a wall.

There was no chance of watching TV news coverage, anyway. The power was out. Contacting loved ones was also a no-go: Landlines were dead, and ’90s cell phones rarely picked up a viable signal on a good day. So we sat in our cars to listen to the news.

Miraculously, The Times was delivered the next morning, and the sound of the paper being tossed onto driveways provided a semblance of normalcy in the chaos. But what we learned from the printed stories was anything but comforting.

Parts of the 5, 10 and 14 freeways had buckled. Streets were simultaneously flooding and burning due to ruptured water and gas pipes. A newly constructed parking garage on the Cal State Northridge campus had collapsed, support columns twisted like taffy.

The aftershocks — 6.0, 5.7, 5.5 — made everyone jumpy. For weeks, scores of scared Angelenos slept outside, in courtyards and on sidewalks, for fear that their apartment buildings might collapse. Surely this is unimaginable to younger Angelenos: Of L.A. County’s 10 million residents, according to the census, 3.8 million hadn’t been born when Northridge hit.

Traumatized office workers bypassed elevators and huffed up the stairs. And like many motorists, I would no longer stop under a bridge or overpass, no matter if it meant there was a big, empty gap ahead of me as I waited for the light to change.

We became familiar with terms like “red-tagged” (meaning a building had been marked by the city as unsafe to enter) and came to know the names of places where the quake hit hardest. The Northridge Meadows apartments became a central focus of the city’s mourning after 14 of the 57 people who were killed in the tremor were found crushed under its rubble.

Santa Clarita City Hall suffered extensive damage.

(Jonathan Alcorn / For The Times)

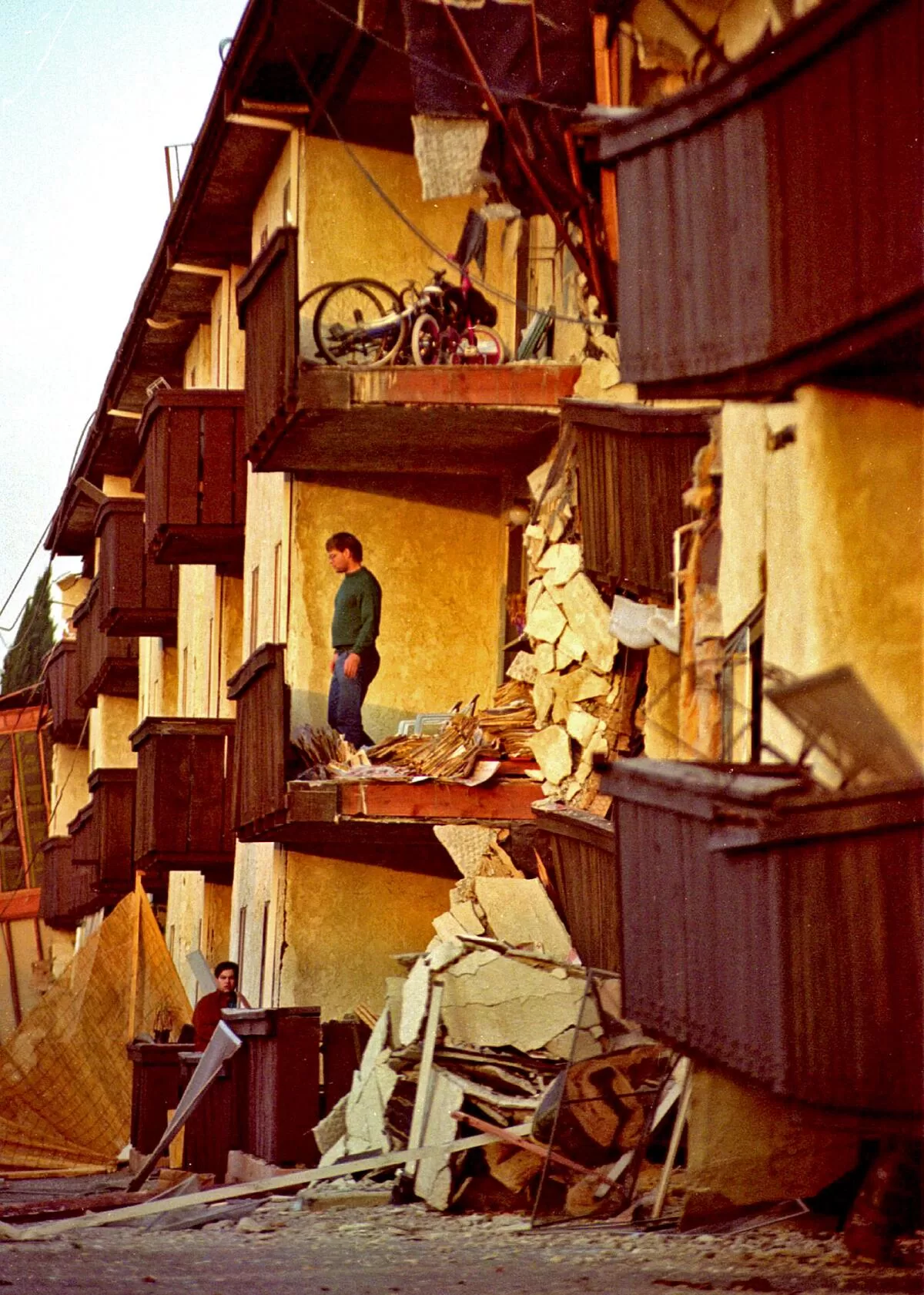

Later I’d see the extent of the destruction firsthand while driving through Hollywood, where the sides of older, multistory brick buildings had crumbled, exposing their contents like rooms in a dollhouse: kitchens with plates still on the table, a jacket draped over the back of a couch. In other spots, old houses that had been knocked off their foundations lazily sagged to one side.

The city looked broken, and Time magazine declared that Los Angeles was going to hell. But we didn’t. So maybe now it is five times more expensive to live here, and traffic is off the charts, but we’re still here, despite the shaking, the riots and the gang warfare. And I’ve learned to always keep a pair of shoes by the bed.