He has been a “Hamrawi” for decades – living through Hamra’s peaks and troughs, including the dark days of the civil war, which, despite their harshness, brought people together.

“There was resilience and solidarity and hope for freedom against the enemy that wanted to destroy Beirut,” Bakhti, now in his 60s, tells Al Jazeera in his shop.

That atmosphere of “light and hope”, Bakhti says, stands in stark contrast to the ongoing slaughter in Gaza today, where each day new horrors are relayed to the world by the few remaining journalists on the ground.

Hamra’s heyday

Long seen as a Middle East cultural and intellectual hub, Hamra had everything from movie theatres to publishers, to cafes full of political dissidents or exiles from around the region in the years leading up to the Lebanese Civil War.

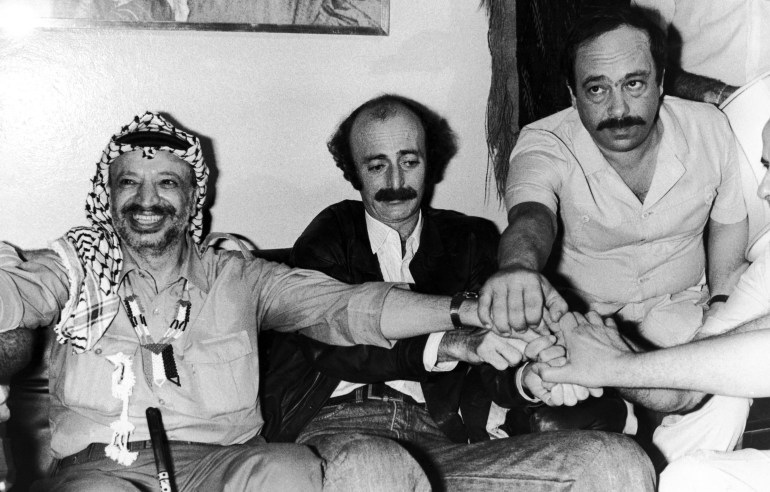

Among the exiles were many Palestinians, including Yasser Arafat, leader of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, and famous Palestinian writer and revolutionary Ghassan Kanafani. They had come to Lebanon along with the rest of the Palestinian political leadership after being expelled from Jordan after its 1970 civil war.

After the 1967 war in which Israel occupied more of Palestine, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were violently displaced from their homes in a second wave of expulsions after the Nakba of 1948.

Many ended up in neighbouring countries, including Jordan, from where resistance fighters launched attacks on Israel, drawing retaliations that eventually led to Jordan expelling them.

Arafat and the Palestinian Armed Struggle Command had by then already signed the Cairo Accord with Lebanon, essentially approving the presence of Palestinian fighters and granting Palestinian control over Lebanon’s 16 Palestinian refugee camps.

Israel used the presence of Palestinian resistance as justification for invading southern Lebanon and besieging West Beirut in 1982.

The siege and aggression by Israel and their domestic allies the Lebanese Forces live on for West Beirutis who find it hard to forget what then-US President Ronald Reagan reportedly called a “holocaust” in a phone call with then-Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin.

Parallels

Many West Beirutis see parallels between the violence of 42 years ago and what is widely acknowledged as an ongoing genocide in Gaza.

“The only difference now is how many people are dying,” Ziad Kaj, a novelist and former member of the city’s Civil Defense Unit, said.

More than 21,000 Palestinians have been killed since October 7, about half of them children. In the siege of West Beirut, some 5,500 people in Beirut and surrounding suburbs are estimated to have died, with staff at one hospital saying up to 80 percent of casualties were civilians.

“I’m not surprised [by the Israeli tactics],” Kaj said.

In 1982, the Israelis and the Lebanese Forces set up checkpoints around West Beirut and cut off electricity. Communication with the outside was rare as phone lines were down.

Israeli officials called on civilians to leave West Beirut and charged Arafat and the PLO with “hiding behind a civilian screen”.

Medical supplies, food and other necessities were severely restricted and scarce, despite occasional attempts to smuggle essentials in.

“West Beirut was surrounded,” Kaj said. “There was no bread, water, or gas, and near-daily bombardment came from land, air and sea.”

“In the morning we would look for bread and often we wouldn’t find it,” Abou Tareq, a resident of Hamra in his 70s, told Al Jazeera. “Vegetables and meat weren’t available at all.”

History is being repeated today in Gaza, where Israeli officials frequently accuse Hamas of using “human shields” and 40 percent of the population is at risk of famine.

In Beirut, the water shortage meant residents had to resort to sweet carbonated drinks or unclean well water that caused stomach ailments. In Gaza too, people have been forced to drink non-potable salt water.

And much like in Gaza, there were so many casualties in Beirut that doctors did not always have time to administer anaesthesia.

Typhoid and cholera spread like wildfire among Beirut’s children after the lack of garbage collection led to an increase in rat bites. Stress was pervasive, with accounts saying the bombing caused “extreme psychosomatic effects”.

People in Gaza have seen an increase in meningitis, chickenpox, jaundice and upper respiratory tract infections as their healthcare system has collapsed.

Shouting at a Beirut sky

“Sometimes the bombing went on for 24 hours straight,” Bakhti said of 1982.

The famous Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish lived in the Dabbouch building back then, Bakhti told Al Jazeera, pointing down the street.

“One day, he came out onto his balcony and started shouting at the Israeli warplanes.”

US academic Cheryl A Rubenberg described, in Palestine Studies, bombing that started at 4:30am and carried on into the evening. After a week of this, she wrote in 1982, she was suffering “anorexia, nausea, diarrhoea, insomnia, the inability to read or write a coherent paragraph, persistent uterine bleeding and a constant feeling of nervousness and tension”.

Israel’s bombing in Gaza has been non-stop for nearly three months, with only a week-long humanitarian pause in late November.

Many residents of West Beirut fled the city to houses in the mountains or East Beirut, though some stayed behind to work or to try to keep squatters away from their property.

Bakhti stayed in West Beirut to keep an eye on his relatives’ homes. “I had many keys and I would go check on their houses,” he said.

“I went to check on my parents’ house and there was white phosphorous residue on the walls.”

Beirut’s hospitals struggled to deal with burn victims after Israel used phosphorus on West Beirut, where 500,000 people lived, including many who were internally displaced from south Lebanon.

International human rights organisations have documented Israel’s unlawful use of US-supplied white phosphorus in Gaza and south Lebanon since October 7.

“We lived the [1982] siege but this [Gaza] is genocide,” Bakhti said.

“This is worse than death.”