Thirty years ago, the veil of secrecy over confidential cabinet documents that informed decision-making at the highest levels of the Queensland government was under threat.

Key points:

- The 1993 cabinet papers show Wayne Goss was heavily involved in Queensland’s Mabo response

- Cabinet papers are kept confidential for 20 to 30 years, but this is being reduced to 30 days

- The Goss cabinet was more concerned with imposing a stricter limit on what could be made public

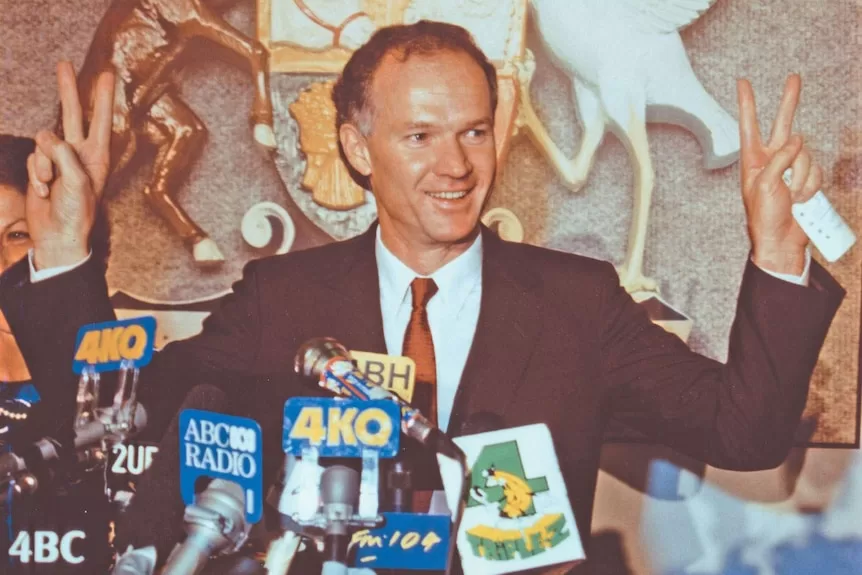

In 1993, with Wayne Goss in his second term as premier, his ministers discussed a move from the state’s information commissioner to make more material public.

In response to an application under new Freedom of Information (FOI) laws, the commissioner had decided to release details of a submission that had gone before cabinet.

The commissioner believed the material in question — about half of the submission — was merely factual in nature and ruled it be made public.

The decision prompted swift action from the Goss government, which feared the ruling would set a precedent for even more secret cabinet information to be publicly aired.

When it introduced the Freedom Of Information Act in 1992, the government had never intended for such large parts of these normally confidential documents to be released.

In a meeting in October 1993, the cabinet signed off on a proposal to tidy up FOI laws and impose a stricter limit on what could be given to the public.

Cabinet documents from the time – only now being unveiled 30 years later – show the then-government was aware their actions would attract criticism and be viewed as controversial.

To this day, cabinet documents in Queensland continue to be exempt from release under Right to Information laws.

They are also kept confidential for 20 to 30 years before being publicly released.

But soon, this will change.

From 30 years to 30 days

Thirty years after the Goss government shored up protections for cabinet documents, the Miles government is preparing for a major overhaul.

From this year, the wait will be reduced to just 30 days in response to calls for changes in the 2022 Coaldrake report into the public service.

At a press conference marking the release of 1993 Queensland cabinet papers, Communities and Arts Minister Leeanne Enoch said the new 30-day regime would begin in the first half of 2024.

She said agencies were still ironing out what documents would be released under the new laws.

“Of course, that’s not retrospective. Those cabinet minutes will be released 30 days from their creation,” Ms Enoch said.

State archivist Louise Howard said personal information or material that posed a “security issue” would still remain confidential for 20 years.

“It’s usually a very small amount, but it is around balancing the protection of personal information and the transparency of the records,” she said.

Goss government responds to Mabo

In 1993, one of the biggest issues the Goss Labor government navigated was the fallout from the Mabo High Court decision.

The landmark 1992 ruling rejected the notion of terra nullius and recognised native title in Australia.

The 1993 cabinet minutes show Mr Goss was heavily involved in Queensland’s Mabo response – providing multiple briefings to cabinet throughout the year.

This included an update he gave in June after he attended a meeting with then-prime minister Paul Keating and fellow state leaders to negotiate a national response.

“The Queensland government will continue to negotiate an outcome for Queensland which protects Indigenous interests in land while providing certainty in land dealings that may now be or will be subject to native title,” the premier wrote in his cabinet submission.

The cabinet would later sign off on “interim administrative procedures” for land dealings and grants beyond June 30, and tasked the office of the cabinet to implement the state’s Mabo response.

Mr Goss also brought an information paper before cabinet that was to be used by the government to address community concerns about Mabo.

“Given the degree of confusion and uncertainty in the community in respect of Mabo, it is necessary that the Queensland government allays fears by setting out the facts relevant to the implementation of the decision in Queensland,” Mr Goss wrote in his submission to cabinet colleagues.

Ms Enoch, who is now Queensland’s Treaty Minister, said the Goss government was trying to strike a balance as it implemented the Mabo decision.

She suggested there was a great deal of conjecture in the community about how Mabo would be implemented.

“Earlier this year, we passed legislation with regards to a path to treaty where we are still trying to find ways to balance our relationships going forward,” Ms Enoch said.

“So, there is a great parallel in all of that. Very interesting conversations in the cabinet with regards to the Mabo decision and native title and what it meant for Queensland.”

Towards the end of 1993, Mr Goss’s cabinet gave the green light to a state-based native title bill that passed parliament just weeks later – supporting the roll out of the Commonwealth’s native title laws.

Getting rid of first-class travel perks

Former Cairns MP Keith De Lacy served as treasurer during the Goss government.

According to historian and University of Queensland adjunct professor Ruth Kerr, Mr De Lacy was very contentious when it came to managing the spending of cabinet ministers.

“Supported by the premier, the cabinet was very diligent and contentious about managing the funds so that it was responsible,” Dr Kerr said.

In one cost-saving exercising in 1993, Mr De Lacy pushed for a freeze on MPs taking first class flights that were more than three hours.

The cabinet documents show the move, which was formally adopted, would likely save taxpayers about $65,000 a year.

The Goss cabinet also signed off on changes to limit the use of mobile phones by MPs.

The parliamentary services commission had estimated mobile phone services, then used by 61 of the 89 MPs, would cost about $186,602 per year if each made five, five-minute calls every day.

That would equate to an annual phone bill of more than $3,000 per year for each MP using the emerging technology.

The cabinet agreed to a proposal to cap the call charges for each MP to $1,000 per year.

Stalking becomes an offence

Among the major reforms taken up by the Goss government in 1993 was making stalking a criminal offence.

In his submission to cabinet, attorney-general Dean Wells pointed to submissions from women’s groups worried that existing laws were failing to protect women from domestic violence.

“Although not gender specific, the proposed amendment is primarily aimed at conduct ‘targeting’ of a woman by a man who causes the woman to be fearful of his attentions towards her,” he wrote.

“The aim of creating a stalking offence is to pre-empt violence by a stalker who will not leave the other individual in peace and privacy; usually arising from, but not confined to, domestic relationships.”

Other decisions the Goss government made in 1993 included giving millions of dollars towards a redevelopment of Lang Park and expanding unpaid parental leave in the public service to include men.

The cabinet also authorised funds to fight a locust plague that was threatening crops, and changed trading hour laws to ensure real estate agents could open on ANZAC Day to cater for tourists.