Seligman’s American citizenship has not stopped him from being something of a hero in the world of Chinese psychology. His theories on well-being — which carry the gravitas of global scientific credibility — are embedded in Chinese education policies from kindergarten onwards. Grade-school children there know who he is. And Zhao believes Seligman’s popularity will help his mental health AI “coach” stand out in the Chinese market. “Marty has a big brand name,” Zhao said. “With his endorsement, a lot of people would come to use it, at least out of curiosity.”

But even for the Chinese citizens who Zhao hopes to help, there’s a risk — one that exposes another facet of the new landscape of AI.

To talk to the chatbot, people type or speak into their computers, sharing confidential information about their lives. In the U.S., that would raise the question of which tech companies are listening and possibly selling that data bout you.

In China, where the government is deeply concerned with monitoring citizens’ thoughts, there’s a far more immediate risk. The ruling Chinese Communist Party’s pervasive electronic surveillance policies mean Chinese users of the virtual Seligman may unwittingly be sharing their thoughts with authorities — who could access or interpret it as criticism of the one-party state.

Beijing has long wielded

false diagnoses of mental illness to target dissidents with arbitrary

detention in state-run institutions. The virtual Seligman could provide Chinese authorities a potential treasure trove of information on its citizens’ innermost thoughts.

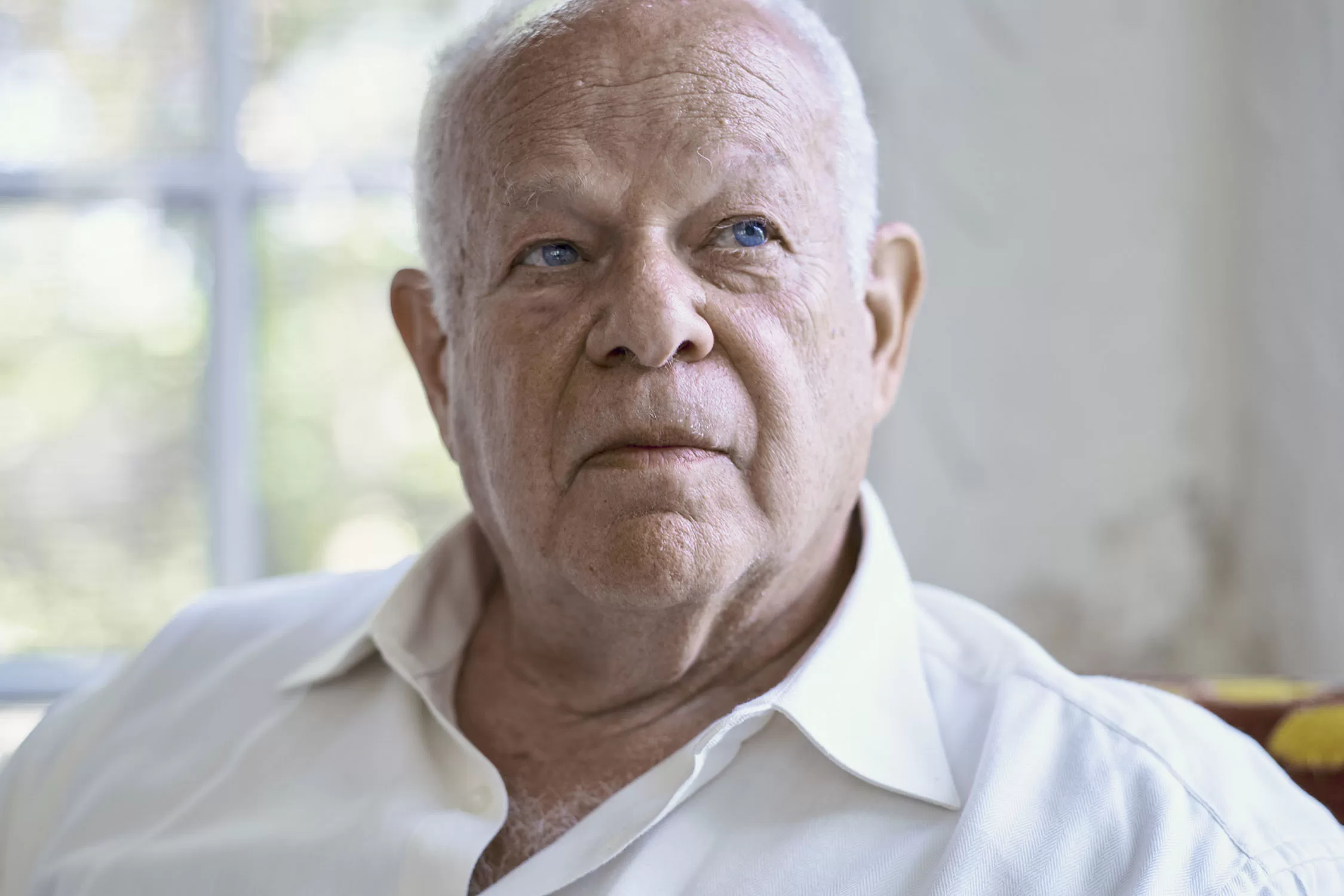

With AI-generated digital replicas poised to enter the mainstream market from Hollywood to Chinese app stores, U.S. policymakers are running out of time to determine the rules surrounding their use. Since that first phone call with Zhao, Seligman says, other AI companies have reached out to him about licensing his library of work to them. “I told them, no, I’m not willing to do it because I don’t know you. I don’t trust you,” he said. Zhao is the exception, Seligman told POLITICO, because of their long friendship.

Seligman is no stranger to powerful government forces

co-opting his work — his research on learned helplessness was used, without his knowledge, to develop the CIA’s “enhanced interrogation” techniques post 9/11. But after numerous experiments with his AI counterpart, he thinks virtual Seligman will do more good than harm in the world.

“It is enchanting to me,” he said, sitting in his study in Philadelphia, “that what I’ve written about and discovered over 60 years in psychology could be useful to people long after I was dead.”

Seligman leaned forward in his chair, as if divulging a secret. “That kind of legacy seems to me as close to immortality as a scientist can come.”

Phelim Kine contributed to this report.