Had the vote passed, an advisory group would have been established to make recommendations to the federal government to alleviate the social and economic inequalities experienced by Indigenous people.

In the referendum, 60 percent of Australians voted against the proposal in a campaign marred by disinformation and public racism.

Still, 25-year-old Jordan Edwards remains pragmatic.

“You can’t lose something you never had,” he told Al Jazeera.

The Gunditjmara, Waddawurrung and Arrernte man is a newly-appointed member in the southern state of Victoria’s First Peoples’ Assembly.

Similar to the proposed Voice to Parliament, the First Peoples’ Assembly was established in 2020 to advance treaty negotiations with the state government.

Separate from the federal government, Australian states have the capacity to introduce such initiatives, despite the failure of the national referendum. Currently, only Victoria and Queensland have committed to the treaty process.

Edwards also acts as the Youth Voice convener, engaging with Indigenous young people around the state to educate them about a process that aims to secure an agreement between local Indigenous groups, known as “traditional owners” and the government, which would allow some self-determination and decision making on matters affecting the community, including land use and resources.

Edwards says it is important that Indigenous young people are included in these conversations.

“I think for young people, [treaty] always been an Elders’ fight, or their parents’ fight. And now, realising that’s on our doorstep, I think we need to grapple with that conversation,” he said.

Looking to the future

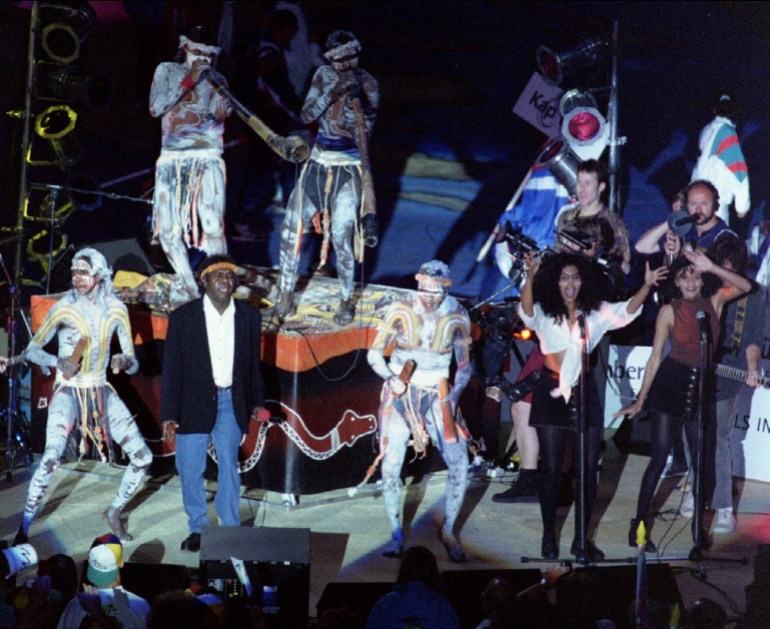

Calls for a treaty between Indigenous Australians and both state and federal governments have been echoing for decades, including in the 1991 hit song Treaty, by Indigenous band Yothu Yindi.

Unlike Canada and New Zealand, the British colonial powers did not form treaties with Indigenous people in Australia, instead declaring the land “terra nullius” – nobody’s land – a legal fiction that took more than 200 years to be overturned.

Victoria’s state government committed to establishing a treaty process in 2018, which is set to be cemented in 2024. Edwards says a treaty is important for Indigenous communities and could especially affect young people into the future.

“They are our largest demographic in our population. So, we actually need young people there because it will affect them as a majority,” he said.

While non-Indigenous Australia has an ageing population, Indigenous communities have far more younger people. A 2021 census showed there were 60,000 Indigenous people in Victoria, with about half of them under the age of 25.

Edwards’s focus on young people is shared by Esme Bamblett who is also an elected member of the First Peoples Assembly and the Elders’ Voice convener.

“We need to think about seven generations’ time,” she told Al Jazeera.

“Personally, in seven generations’ time, I’d like my children and my descendants to have generational wealth, I want them to have every opportunity just like everybody else. I want them to know that they are strong and to be proud of who they are and have a strong identity as Aboriginal people.”

Bamblett said the inclusion of an Elders’ Voice at a parliamentary level was important not only to highlight the challenges Indigenous elders face but also to reflect Indigenous cultural protocols.

“A very important part of our culture has been respect for our elders,” she said.

“The heads of all the families were the Elders, and the Elders would get together and they would then decide on issues and actions and there would be a consensus of opinion about what would happen. You learn from a very young age to respect your elders, and to listen to them.”

Indigenous people had lived on the continent now known as Australia for more than 65,000 years, when the British sailed into Botany Bay in 1788.

Their declaration of “terra nullius” paved the way for violent colonisation in the 1800s and punitive assimilation policies that removed Indigenous children from their families well into the late 20th century. Known as the Stolen Generations, this attempt at assimilation was buttressed by strict immigration laws which excluded non-Europeans, known as the “White Australia” policy.

Those policies’ negative legacy continues to be felt by the more than 30 Indigenous nations that live in the state of Victoria.

“Out-of-home care, the incarceration rates, unemployment – all these things have really impacted on our mob [communities],” Bamblett told Al Jazeera.

“And there’s a lot of our elders who are caring for their grandchildren.”

Truth for change

Similar to the structure of the proposed – and defeated – Voice to Parliament, Victoria’s First Peoples’ Assembly is made up of 32 members elected by local Indigenous communities who each represent the concerns and cultures of traditional owner groups.

First Peoples’ Assembly Co-Chair Ngarra Murray told Al Jazeera that Indigenous people needed to be “in the driver’s seat when it comes to the issues that affect us”.

“To be able to distil and articulate the views of our communities is powerful in itself and provides us with a strong platform to advocate for and against certain policies and practices that affect our communities,” she said.

Murray – who is from the Wamba Wamba, Yorta Yorta, Dhudhuroa and Dja Dja Wurrung peoples – said self-determination was vital if the impacts of colonisation were to be rectified.

“We are the experts on our own lives, we just need the freedom and the power to make the decisions about our culture, communities and country,” she said.

Alongside the First Peoples’ Assembly and treaty negotiations, a truth and justice commission has also been established to investigate both historical and ongoing injustices against Indigenous people since colonisation.

Yoorrook – meaning “truth” in the Wemba Wemba/Wamba Wamba language of northeastern Victoria – has a mandate to establish an official record on the impact of colonisation and make recommendations to address the ongoing challenges facing Indigenous people.

Professor Eleanor Bourke, a Wergaia/Wamba Wemba Elder and Chair of Yoorrook, told Al Jazeera that the truth-telling process was vital in the fight for change.

“Telling the truth about injustice can help build shared understanding,” she said. “But understanding on its own is not enough. We must also create transformative change. Being heard is the first step.”

Yoorrook’s most recent report, Yoorrook for Justice, investigated the links between child welfare and adult imprisonment and found there was a direct “pipeline” between the two.

The report also said that without major reforms, First Nations’ children would continue to be at greater risk of entering the child protection and criminal justice systems from birth.

Nationally, Indigenous children are 11.5 times more likely to be in state welfare than non-Indigenous children, while Indigenous adults are 14 times more likely to be imprisoned than non-Indigenous adults.

“The report found that First Peoples faced racism and injustice at almost every turn across both systems and made strong recommendations for reform,” Bourke told Al Jazeera.

“Yoorrook is still waiting to see when, and how, the Victorian government will respond. There were promising signs of progress during the inquiry process. This includes commitments by government to improve the state’s bail laws, to repeal public drunkenness laws and to raise the minimum age of criminal responsibility.”

‘Confronting and raw’

The Yoorrook for Justice inquiry began in 2021 and held 27 days of hearings. Notably, Victoria Police Chief Shane Patton publicly apologised for the systemic racism experienced by Indigenous people at the hands of the police, and then-premier Daniel Andrews said that the over-representation of Indigenous people in child protection and prison was “a source of great shame”.

Alongside the investigation into the impact of government systems, Yoorrook also hears personal stories from First Nations community members.

These can include personal experiences of racism, the justice system and historical family narratives.

Such intimate stories are heard by “truth receivers” such as Lisa Thorpe.

“There is a mixture of stories we are hearing but they are almost always confronting and raw, and involve trauma,” she told Al Jazeera.

“People who’ve been through the criminal justice system, who’ve been mistreated in jail, who’ve had children taken off them, who’ve only just survived – these are the stories we are hearing. Many of these stories I’ve heard before but never in an official way like this.”

Thorpe, who is from the Gunnai, Gunditjmara, Wamba Wemba, Boonwurrung and Dja Dja Wurrung nations, also said that such stories were emanating directly from her family and community.

“So many of the stories I hear affect me personally, I relate to them or they are stories of people I love and care about,” she said. “But hearing them is also part of healing for me.”

While the failure of the Voice to Parliament was deeply disappointing to many around the nation, Indigenous people are demonstrating a resilience and fortitude to address the challenges of colonisation and hold the government to account.

Like Jordan Edwards and Esme Bamblett, Thorpe hopes the initiatives of the First Peoples’ Assembly, treaty negotiations and the Yoorrook Justice Commission will bring about a fairer future for her children and the generations of Indigenous Australians to come.

“Yoorrook has an opportunity to make real change, to hold the government to account and question the systems causing injustice to our people,” she said.

“My one goal is to make life better for my children than it was for me. This is a real opportunity to contribute and make positive change for the next generation and there might not be another opportunity like this again.”