This was a significant departure from Hollywood’s traditional and lucrative strategy, which goes like this: Once a show runs its course, keep selling it and reselling it to other networks and services for as long as possible. This is how something like “Seinfeld” keeps generating returns for years and years after its original lifespan.

Lately, though, the walls around the streamers’ orchards have started to crack. Executives have become increasingly willing to license titles from their libraries to third parties, including Netflix, as studios mine their catalogs for much-needed cash.

Certain acclaimed HBO shows that once streamed exclusively on Max, including “Six Feet Under” and “Insecure,” are now also available on Netflix. Past seasons of the Warner Bros. Television sitcom “Young Sheldon,” which debuts its last season on CBS next year, are also streaming on Netflix. (To be sure, though, HBO and Max are keeping “Game of Thrones” and other blockbuster series to themselves.)

This month Disney and Netflix reached a licensing deal that would bring 19 seasons of the ABC stalwart “Grey’s Anatomy” to Hulu in a “co-exclusive” arrangement, while Netflix will get to stream Disney-owned shows including “How I Met Your Mother,” “Lost” and “Home Improvement.”

“The streaming wars are over and Netflix has come out on top,” said John Mass, president of Content Partners, a Los Angeles-based investment fund and asset management company that focuses on the entertainment business.

“That doesn’t mean that these other streaming platforms won’t survive or thrive,” Mass said. “But it is clear that the others cannot rely solely on their own content — they need to expand their models so they include not only their own existing libraries and new content that they produce, but also incorporate licensing — both of their competitors’ content as well as be open to licensing their content to competitors.”

Or as Warner Bros. Discovery content sales president David Decker said in a New York Times article, licensing is “becoming in vogue again.”

The trend comes as the media companies pull back on their streaming cash incinerators. A Monday research report by Morgan Stanley estimated that during the last 18 months, the entertainment industry has recorded $8 billion in impairments from removing streaming content. “Batgirl” studio Warner Bros. Discovery was, no surprise, the biggest cutter of the bunch, followed by Disney, which deleted shows including “Willow” from Disney+ amid the broader streaming purge.

The report, led by analyst Benjamin Swinburne, notes that the push to maximize streaming profits “includes moving away from a vertically integrated approach to greater levels of non-exclusivity or third party licensing.” These decisions are difficult but necessary as the streaming business braces for consolidation. “The prospects of many profitable [streaming] services in the market long-term is in our view unlikely,” the Morgan Stanley analysts wrote.

Streaming is clearly here to stay and studios are still spending a fortune to supply their direct-to-consumer services with original shows and movies.

But the streaming business is maturing. It’s been clear for some time that the industry has entered a new phase in which the legacy media companies that ramped up their streaming investments three or four years ago no longer prioritize attracting subscribers at all costs. Trying to catch up with Netflix is out. Profits are in.

At the same time, companies including Netflix are seeing the value that comes from having older shows, like “Suits,” that are produced by rivals but can reach new audiences on streaming, thereby boosting engagement and reducing churn.

The practice of licensing for streaming never went away. Sony Pictures has for years had a deal with Netflix where its movies stream after theatrical release, which is how “Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse” and Jennifer Lawrence’s raunchy comedy “No Hard Feelings” hit No. 1 on the platform’s weekly U.S. film charts. Sony is unusual among its rivals in that it doesn’t have its own Netflix competitor, seeing itself as an arms dealer in the battle for viewers’ attention.

But other studios have started to change course, in another example of Hollywood reverting to the mean. Many of the trends that seemed to make sense in a COVID-afflicted economy, with theaters and music venues shut down, have swung back in the other direction. For example, Disney is planning theatrical releases for movies that skipped cinemas during the pandemic, including Pixar’s “Soul,” “Luca” and “Turning Red,” before the summer release of “Inside Out 2.”

The shift back to third-party deals is a win for Netflix, which in its early days built itself up with the help of a steady supply of already popular movies and TV shows, such as animated hits from Disney and nostalgic TV faves like “Friends” and “The Office.”

Netflix last week disclosed that during the first half of 2023, 45% of viewing hours were generated by licensed titles.

It makes sense that the reruns, as we used to call them, would account for a sizable portion of viewership, though the Los Gatos, Calif.-based streamer’s originals such as “The Night Agent,” “Ginny & Georgia” and South Korea’s “The Glory” dominated the top of global charts. Library shows tend to have more episodes. But that’s the point. Older material helps keep subscribers in the fold.

One holdout from the practice of licensing original content is Netflix itself. That could change at some point, but for now the truism seems to be that what works for Netflix doesn’t necessarily work for everyone else, and vice versa.

“I do think that we can add tremendous value when we license content,” Netflix co-Chief Executive Ted Sarandos told reporters last week. “I’m not postitive that that’s reciprocal.”

You’re reading the Wide Shot

Ryan Faughnder delivers the latest news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Stuff we wrote

Jonathan Majors dropped by Marvel after conviction. Marvel Studios has dropped Kang the Conqueror actor Jonathan Majors after the actor was found guilty of assault and harassment on Monday.

Netflix releases trove of viewership data for 18,000 shows. What does it tell us? Netflix has released its first semiannual engagement report for a multitude of shows and movies on the streaming service, in an effort for greater data transparency.

Behind the calamitous fall of hip-hop mogul Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs. In the wake of multiple lawsuits filed against him, former members of Combs’ inner circle told The Times that his alleged misconduct against women goes back decades.

With ‘Ninja Turtles’ and ‘Paw Patrol,’ Paramount’s animated franchise strategy pays off. Paramount Pictures is leaning into franchises like “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles” and “Paw Patrol,” which have generated $2.5 billion in retail sales this year and done solid business at the box office.

Hollywood’s animation workers are unionizing at a rapid pace. Here’s why. Thanks to key wins by production workers at Disney, Warner Bros. Discovery, Nickelodeon and other animation giants, animation guild membership is booming.

The Docket

Film shoots

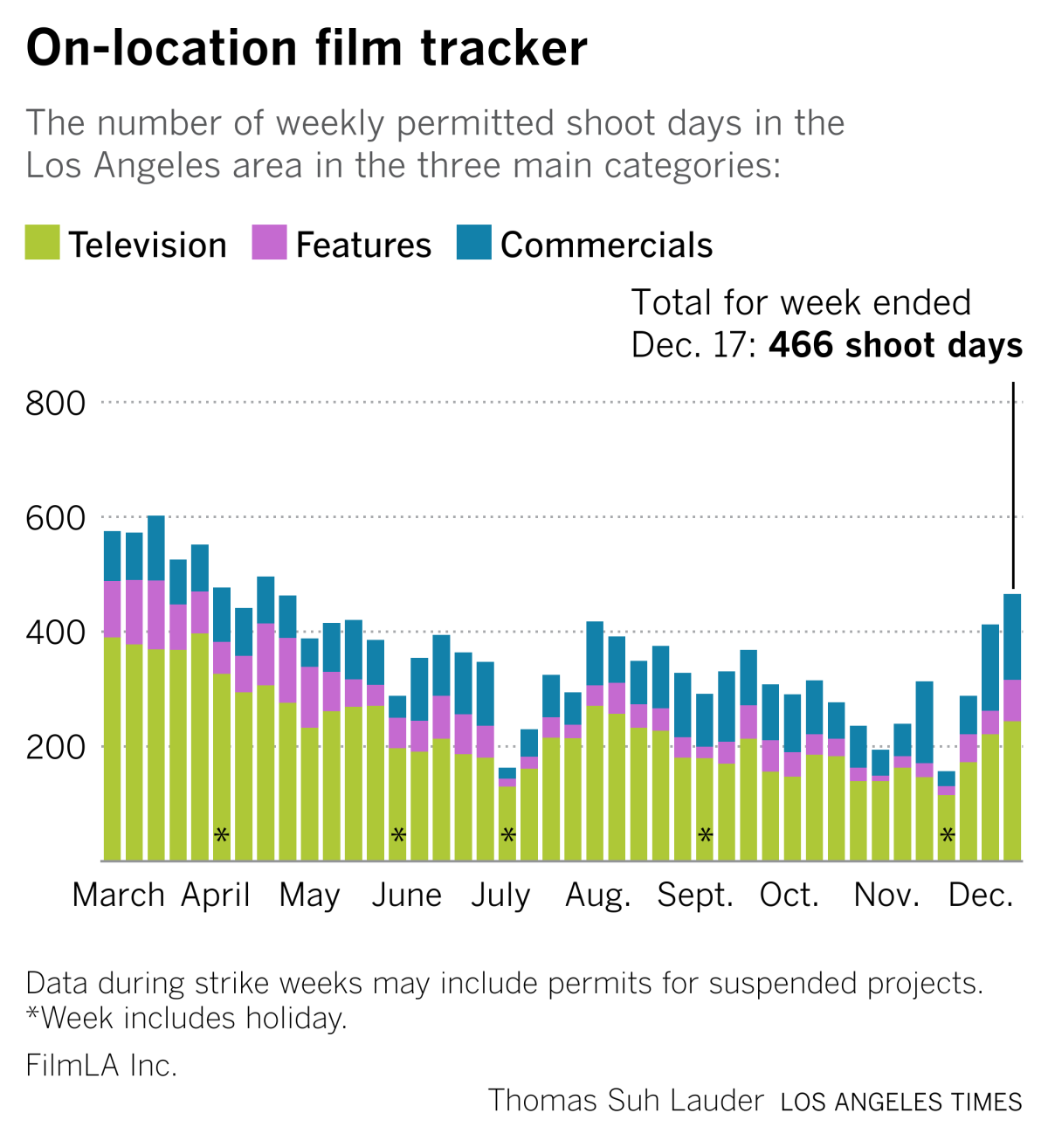

The post-strike production recovery continues in Los Angeles, according to FilmLA data.

Best of the web

— Google’s AI-powered search product is being tested on roughly 10 million users, and that’s a problem for news publishers’ traffic. (Wall Street Journal)

— A detailed look at the owners of “Sound of Freedom” studio Angel Studios and their Provo, Utah-based family empire that operates in unusual ways. (Rolling Stone)

— How a $13.99 Snoopy doll sparked a Gen-Z craze. The iconic Peanuts character is gaining new, younger fans and fueling a quest for a puffer-clad plush. (WSJ)

— Lastly, I’m a little late in noting this one: WSJ’s Erich Schwartzel on the tragedy of former Disney executive Dave Hollis.

Finally …

Finally caught up with this year’s album from L.A. rocker Blondshell, and it’s one of my favorites of 2023. Here’s The Times’ profile from way back in February.