Sometimes, for reasons that she could not fathom, Kemi would feel immense sadness come over her.

She would for instance, be on a jovial phone call with a friend, and in a split second, become overwhelmingly sad and begin to ruminate on dark thoughts that would eventually bring her to a depressive state.

In those times, her actions and manners would be so out of character that she would be unrecognizable to those who know and love her.

“I just shut everybody out and would like to be by myself; I would lock my house, I wouldn’t try to call or reach out to anybody. I just remain in a bubble in my head, battling with the depression,” Kemi explains.

Kemi would not only shut out her loved ones, she would also become uncontrollably irritant, and as a result, flip out at those physically close to her.

After some time, the sadness would go away and with it would also go the irritation. The temporal nature of the episodes didn’t help much, because after she regains full control of herself, she has to pick up the pieces of damage caused by the shortlived depressive episode. She would barely be back on good terms with those she had offended before the darkness would, like an unwanted visitor, come again.

Time and time again, this happened until Kemi began to believe her existence was “a flaw.”

“I was misconstrued by people; it messed up my relationship with people and my family, even my mum who is my closest friend,” she said, remembering that her mother often wondered why she would be jovial one minute and then box herself up the next.

While it hurt Kemi that her family and friends viewed her in a different light than she would prefer, she did not blame them as she too could not grasp what was happening to her and why she behaved the way she did.

Kemi went through this from 2016 until 2022 when she came across a post on social media that made her realise she might be suffering from a premenstrual condition known as Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD).

“It popped up on my timeline, then I researched and found out what it was,” Kemi remembers.

The problem with PMDD

PMDD is a kind of premenstrual symptom different from the commonly known PMS (Premenstrual Symptom). It is a “much more severe” form of PMS which may affect women of childbearing age, known to occur 1-2 weeks before the commencement of the monthly menstruation, and it is marked by symptoms similar to those suffered by Kemi, including irritability, lack of control, anger, depression, poor self-image, crying spells, moodiness, confusion, heart palpitations, and other psychological and physical symptoms.

As of 2003, it was estimated that “3-8 per cent of women of reproductive age meet the criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder,” while assessments of published reports at the time suggested that its prevalence was higher than speculated as 13-18 per cent of women were estimated to suffer from it.

An article published in the same year in Science Direct journal, an online source for scientific, technical, and medical research, asserts that the disorder is on the same level as major recognised disorders because of its burden and the disability-adjusted life years (DALY) lost due to its repeated cyclic nature.

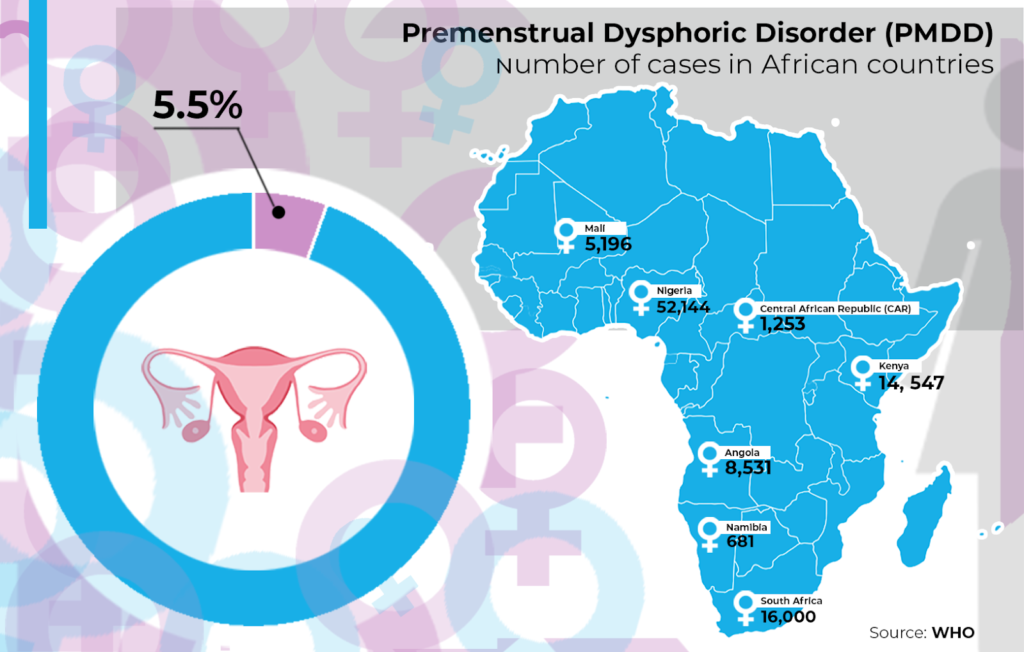

Much more recent data (2023) provided by the World Health Organisation (WHO) indicate that the disorder is prevalent among 5.5 per cent of women of reproductive age.

Specific figures for African countries include 52,144 women in Nigeria, 1,253 in the Central African Republic (CAR), 5,196 in Mali, 8,531 in Angola, 681 in Namibia, 14, 547 in Kenya, 16,000 in South Africa, etc.

But despite the numbers and its global prevalence, the awareness level of this disorder is considered to be low and as a result, many women unknowingly battle with it sometimes to the point of immense danger ranging from self-harm and suicide.

Azuka who spoke to HumAngle, for instance, usually had thoughts of self-harm, (due to the effects of PMDD) and was in danger of acting on them but like Kemi, she too did not know what was happening to her.

Azuka braved through a series of ordeals for four excruciating years before she found out through a period app, that it was linked to Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder.

“When you log in how you feel, you see stuff [write ups] that talks about it,” Azuka said, to explain how the app helped her.

Like Azuka, numerous women with the disorder suffer from this. A 2021 study published in Science Direct’s Journal of Affective Disorders says thoughts of self-harm are not alien to women with the disorder; in fact, it suggested that such women are more susceptible to suicidal thoughts, attempts, and plans.

In a recent study carried out to determine the “prevalence of lifetime self-injurious thoughts and behaviours” among people who possibly suffer from the disorder, a “global sample of 599 patients reporting prospectively confirmed diagnosis with premenstrual dysphoric disorder,” revealed that 72 per cent of those people have had suicidal thoughts, 49 per cent have planned to commit suicide, 40 per cent of them have planned an attempt, while 34 per cent of them have outrightly attempted to commit suicide. Fifty-one per cent of them have suffered non-suicidal self-injury.

The study indicates that the rates of suicide ideation among the study samples are much higher than is obtainable among the general population of people.

Reduced quality of life

The International Association of Premenstrual Disorders, a UK-based resourcing platform for women with Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD) and Premenstrual Exacerbation (PME), essentially explains PMDD as being caused by the brain’s inability to adapt to the monthly changes and fluctuations that occur across a woman’s cycle.

While this has been established as the cause, the reason behind the brain’s inability to adapt to said changes remains largely unknown.

This vacuum of knowledge on PMDD is connected to the lack of research and awareness around the topic as well as the fact that women are generally understudied due to the gender gap in research.

In fact, PMDD was only acknowledged as a disorder and included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual in 2013. Even after that, some professionals still argue if it is indeed a disorder.

However, the disorder has been known to drastically alter the life experiences of women who suffer from it.

“Based on the Global Burden of Disease (GBD), it is estimated that those with PMDD experience a total of 1,400 days or 3.835 years of Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) lost due to the disorder,” the International Association of Premenstrual Disorders writes.

Research has also shown that aspects of women’s lives such as relationships, jobs, and general outlook tend to suffer due to the disorder.

“Quality of life among PMDD participants was lower, especially in the social relationships domain. All areas of functioning were also significantly affected in PMDD participants,” the conclusion of a 2021 study (on the topic) read, adding that “the identification of the disorder should lead to treatment of more women with PMDD improving their quality of life and functioning.”

“They have maladjusted emotions, family relations, and social functioning. They experience higher somatisation, obsessive-compulsive, depressive and anxiety symptoms. The burden of the illness is high,” another study published in the Egyptian Journal of Psychiatry read.

Like the previously referenced study, this one also noted that “appropriate recognition” of PMDD would reduce the suffering of affected women and improve their quality of life.

Managing PMDD

When it comes to treating Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder, Obstetrician and Gynaecologist at the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital (UMTH), Dr Fiona Gideon was clear on one thing: self-sought remedies can not be relied upon.

“Self-management is not sufficient,” she said to HumAngle. “Affected women should seek professional help.”

The IAPMD also points out that treatment and management plans for PMDD are not exactly uniform as the available options do not work for everyone living with the disorder.

Its advice to “work with your healthcare and support team to find the best treatment option for you” also reinforces Dr Gideon’s statement.

Some management options shared by the OBGYN doctor include “change in eating habits, pharmacological agents for low risk [cases] and hormonal therapy for high risk [cases,]” all of which should not be undertaken except on the advice of a trained professional.

Oral contraceptives, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), chemical menopause (GnRH Agonists), and surgical menopause (THBSO) are some options that fall under a category of treatment mentioned by Dr Gideon.

PMDD in the Nigerian Sphere: What chances do Nigerian women have?

Considering the low PMDD awareness globally (even in medical circles), especially in countries considered to be top contributors in studies around the disorder, women with PMDD in Nigeria might have a tough time managing it.

To the best of our knowledge, existing PMDD studies conducted in Nigeria (for Nigeria) include a 2004 study into the prevalence of the disorder in one Nigerian University (University of Calabar), a much more recent (2023) but similar one conducted in a University in Nasarawa State, a few others of similar topics and another, comparing the prevalence of PMDD and comorbidities among adolescents in the United States and Nigeria.

Whether the medical bodies in the country have recognised (and moved to tackle) the disorder in Nigeria, is yet to be known or established and as such, women are in danger of medical gaslighting or outright dismissal due to poor knowledge as well as the nature of the disorder which is commonly misdiagnosed as bipolar disorder, even in countries where it has been relatively studied.

A 2023 article on Daye (a UK-based sanitary production company) blog about low PMDD awareness paints a clear picture of what women in Nigeria are likely to suffer; in the article, a 23-year-old woman named Sophie complains that “the ignorance among medical professionals and sexism were major stumbling blocks in the process of having her condition recognised.”

“A lot of doctors I went to see either didn’t know what PMDD was or didn’t take me seriously even though I had tracked my mood and my cycle for months and found the link,” Sophie told Daye.

Sophie’s experience, though based on a lesser-known issue, is consistent with the experience of a Nigerian woman whose case of medical gaslighting saw her suffer through heavy bleeding and cramps, a condition which is considerably well-known among medical practitioners.

The figures around medical gaslighting do not do much for the hopes and chances of women with PMDD in the country. In 2019 for instance, the Medical Council in Nigeria investigated 120 doctors for misconduct concerning medical misdiagnosis. Beyond this, the general lack of awareness as to the depth of the problems caused by PMDD may lead women who suffer from it not to take it seriously.

But there is some reassurance in the response of Dr Gideon who answered affirmatively when asked if there is existing awareness of PMDD in the medical space in Nigeria. “Yes, among the obstetricians,” she told HumAngle.

Ifeoma, a possible PMDD patient (has noted symptoms but is yet to get a diagnosis) who spoke to HumAngle about struggling with the symptoms of the disorder said she has not sought help because it might not be so serious.

“I watered down my feelings and I mentally invalidated it in my head that maybe I am overreacting,” she said.

The response of Cynthia, another woman who spoke to HumAngle about discovering PMDD through social media and personal research, indicates that lack of affordable healthcare might also hinder Nigerian women from getting the help they need as even though Cynthia considers the symptoms threatening, she is unable to do anything about it.

“Yes I do but currently can’t afford it,” she had said when asked if she plans on seeking professional help.

Other factors that may impede the welfare of women with PMDD in Nigeria include the generally poor data collection culture in the country, and period shame which prevents and frowns on free and public discussion of the menstrual cycle and its symptoms.

Cynthia’s wish is that the menstrual cycle and issues surrounding it are not treated as abominable topics as it was through open discussions on social media that she was able to connect her cyclic depressive episodes to her menstrual cycle.

Ifeoma (and all the women who spoke to HumAngle), said they wished they found out earlier as this would have helped them come to terms with it sooner.

Ifeoma also regrets the lack of awareness about PMDD in Nigeria as she was only able to connect the intense mood-related symptoms she feels to her menstrual cycle “after seeing people confirm the same pattern online.”

She wondered too how other Nigerian women living with PMDD who don’t have access to the internet would find out about it.

“I don’t think everyone has this privilege,” Ifeoma said.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.