When Aishatu Muhammed was married off at age 17, she was indifferent. Her husband was a 28-year-old man whose family had a strong relationship with hers. At the time, she didn’t know much about him and they only spoke casually before their wedding.

“I didn’t have much choice when the wedding took place but I wasn’t too bothered about it either,” she told HumAngle.

After the ceremony, the new bride was taken to her husband’s family home where she began a new life. But life didn’t go as smoothly as she had hoped.

Aishatu lived most of her life in Akko Local Government Area (LGA) of Gombe State in North East Nigeria. But life after divorce would soon push her back to the northwestern Kaduna State.

A communal affair

In Fulani communities, marriage is seen as a communal affair. Most importantly, early marriage is viewed as a way to preserve this tradition. This is despite the Child’s Rights Act 2003 which states 18 as the minimum legal age of marriage in Nigeria. The United Nations International Children’s Education Fund (UNICEF) says that five out of 36 states in Nigeria, including Gombe State, did not apply this law to their internal legislation, with some of them having legal marriage age as low as 12.

Aishatu’s biggest bone of contention with her husband as soon as she settled into her married life was his family. “We stayed with his extended family including his mother, grandparents, siblings, and their spouses. I had a good relationship with some family members like his mother and the majority but there were issues with some family members,” she said.

Even though staying with extended family members has some advantages, such as promoting unity and building a strong support system, sometimes it can lead to interference in marriages, misplaced leadership roles, and placing too much burden on a few members which may lead to resentment and arguments.

The biggest conflict the couple faced was in regards to keeping the environment clean. The responsibility always fell on Aishatu. Whenever she tried to raise the need for others to keep it clean, it was not received well.

Aishatu gave birth to a girl a little over a year into the marriage. Unfortunately, the marriage lasted only about five years due to the recurring problems between her and the husband’s family. “He never took my side and pretended not to see what was happening and we also kept having fights over so many things.”

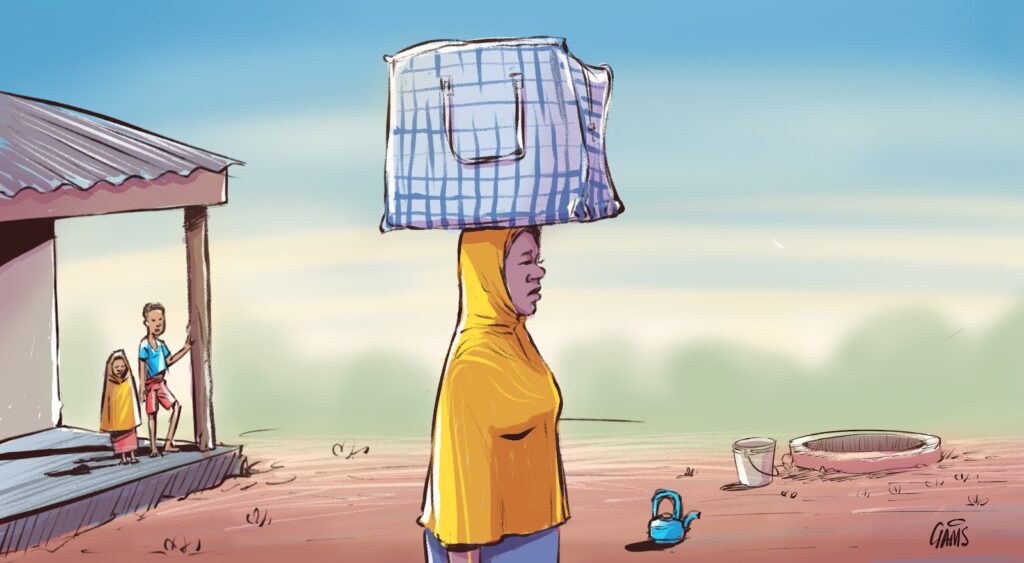

Despite their misunderstandings, as far as Aishatu was concerned, she still did her best as a wife. But after one big argument, she packed up and moved to her mother’s house. The Hausa word for this move is Yaji, a situation where a woman leaves her marital home for her parents’ due to a domestic issue. Usually, the husband is expected to visit in order to negotiate her return. But Aishatu got a divorce letter delivered to her instead. She remembers that time as the year the country’s military head of state, General Sani Abacha, died. This was in 1998.

Under Islamic law, a man has the right to pronounce divorce by writing or saying it out loud. The letter completely annulled the marriage by exhausting the three chances of reconciliation provided by these laws; Aishatu knew instantly that that chapter of her life had closed. She went to retrieve the rest of her belongings from the house, after which she returned her daughter to the family under her mother’s instructions.

Northern Nigeria is said to have one of the highest divorce rates in West Africa, with a high percentage from Kano State, which had an estimated number of over a million cases of registered divorces in 2009 alone.

Aishatu’s mother used to be a successful farmer and tried to give her children the best. So, even after the divorce, she was supportive. But sadly, she soon passed away. “I felt a great sense of loss and felt stuck in life. Especially since the help I used to get stopped coming even from relatives that used to be helpful when my mother was alive.”

Life in Kaduna

But a breath of fresh air came in the form of an invitation. Aishatu’s great-uncle invited her over to Kaduna in the early months of 2000. There was one thing going against Aishatu now that she was unmarried – she had never furthered her education after primary school.

According to Girls Not Brides, an organisation raising awareness on child marriages “73 per cent of Nigerian women with no formal education were married before 18, compared to only 9 per cent who had completed higher education. Further education is almost impossible for some girls, who have little choice but to depend on their husbands for the rest of their lives.”

Moving to Kaduna was a wake-up call for Aishatu. It helped her set her life on track.

“I took every job I could including working as a nanny and house help. I also dabbled in business selling clothes, bed sheets, and other things.” It was during this time that she got a job as a receptionist at a hotel. She left in 2016 but was contacted in 2023 to return due to the commendable work she did in the past.

The State of Nigerian Girl report shows a link between poverty and early forced marriages. Early marriages also lead to high rates of school dropouts, lack of access to healthcare, social and economic services, and poor education outcomes.

At a point, there was pressure on Aishatu from her uncle and his wives to remarry. But it is not as easy as it sounds. She is currently more satisfied with her life as it is than when she was married, she says. “I do want to remarry someday but I am sceptical of men, especially after a bad experience that left me scarred,” she said.

A few years after she returned to Kaduna, Aishatu dated a man for almost ten years. He kept promising her marriage until she saw his wedding pictures on a mutual friend’s social media page. “I was in Gombe when I found out, even though we had been talking throughout.” She became even more weary of trusting men since that incident. The betrayal struck deep and she became more focused on herself.

Aishatu visits her daughter every time she is in Gombe. “Every time I visit the house to see my daughter, I feel glad I have left. I am doing much better than I would have been if I was still married to him and I feel more peace within myself after leaving the house.” Although she tries to visit as often as she can, she hasn’t been able to in a while because the transport fare is high.

“I wish women would understand that their lives do not end when they get divorced. I know unmarried women who are living full and happy lives. There is no difference between married and unmarried women, what matters is what you choose to do with your life.” Aishatu strongly believes that when you do good, good will surely return to you in many ways.

Another love gone sour

In Kaduna, as Aishatu rebuilt her life, another woman was also trying to mend hers.

Rahmatu Hassan* was 18 when she got married. Born and raised in Kaduna, there was no indication her life would take a sad turn after rounding off secondary school. Young and full of hope, she had looked forward to starting a new life with her husband even though his family was not fully in support of his choice.

With her new responsibilities, Rahmatu was unable to further her education. When she was ready to, her husband lacked the finances to sponsor her. Soon after, the problems started.

“When I have an issue with him, his mother never tries to see things from my perspective and when his relatives come to visit, they keep nitpicking on what I did or didn’t do,” she narrated.

Although the families were far apart, Rahmatu endured these frequent visits. Unfortunately, when she tried to explain this to her husband, it became a problem because he never supported her.

“They used to think that he was giving me the world and they didn’t like that. It took our divorce for them to realise that it wasn’t the case.”

Four children later, the marriage crumbled.

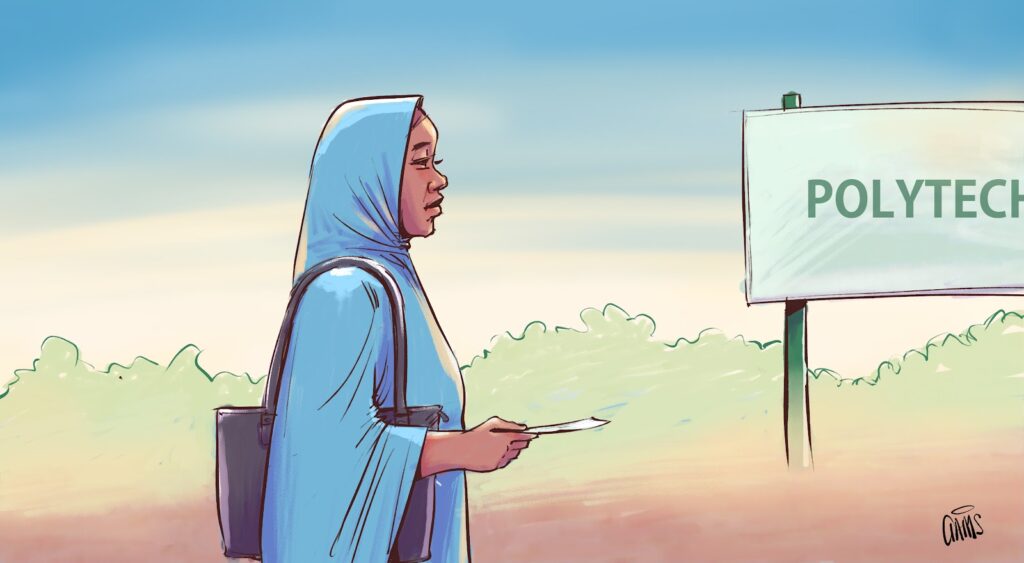

“I left my children, two boys and two girls, with my husband. When I went back home, my father pushed for me to continue my education.”

And so she got her National Diploma (ND) in Cooperative Economics and Management at the Kaduna Polytechnic. “My family was very supportive of my situation and tried their best to help me,” she recalled.

A second try at love

Sometime after her programme, Rahmatu remarried into a polygamous home. This was three years after the divorce. But after the wedding, she found that she had assumed the role of his children’s caretaker. Her husband and his other wife would find excuses to travel, leaving her to handle the affairs of their four children even though she didn’t have any of her own with him. Then, when her children visited, he was cruel to them. He made it clear that he didn’t want them around even though they never slept over.

“It reached a point where I could only see my children when I visited my parent’s house because I couldn’t have them in my own home. That’s when I knew I had to leave. I didn’t have my life when I was married to him. When I went back home, my father tried to encourage me to go back but I told him I could not go back to a man who made it clear he doesn’t like my children even though I am taking care of his own,” she told HumAngle.

But there was a catch here. Rahmatu kept asking him for a divorce but he refused to grant it. That was when she made the decision to take him to court.

Even though men under Islamic law can easily execute a divorce, women can only initiate it by returning the bride price they received at the time of the wedding. But this requires the arbitration of the court and, for many women, this can be exhausting. Divorce proceedings for Islamic marriages are not regulated by the 1970 Matrimonial Clauses Act but by sharia or customary courts.

“A friend encouraged me to go to court. I am glad I was able to fight for my rights. But in my first marriage, I wasn’t old enough to understand what I needed to do.”

Her father encouraged her to go back to school for her Higher National Diploma (HND), but it wasn’t long after she started that he passed away.

It took about two years before she finally got her divorce. “It didn’t even come from the court judgement. He later agreed to divorce me on the condition that I return his bride price, which I did but he put me through so much before that.” Rahmatu felt like he was trying to punish her for daring to leave him.

“I am currently in my final year and will soon be done with school and my last daughter is currently staying with me. I am at peace with my choices and I get to see my children whenever I like.”

Her ex-husband does his part in parenting the children and they never had an issue with custody of the children. “I hope to get a good job as soon as possible so I can do more for my children,” she said.

Now 28, Rahmatu would like to remarry if she gets a good partner. Despite her experiences, she hopes for a better match in the future.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.