Emmanuel (surname withheld) was angry. Here he was at the hospital pharmacy to collect his prescribed medication, only to be told it was not available.

“You would have to return another day for it,” the person at the counter said. The whole episode took place sometime between July and August.

A secondary school teacher under the Kaduna State Teachers Service Board, Emmanuel had sought health care at Ashmed Specialist Hospital. It was his hospital of choice under the Kaduna State Contributory Health Management Authority (KADCHMA). The facility was located at Kudandan, a few kilometres from his home in Sabon Tasha in northwestern Nigeria.

Emmanuel recalled the process it took for him to get the hospital of his choice. Every enrollee was entitled to pick a single facility to visit for medical care. “When I filled out the form at the Ministry of Health, a time was scheduled for me to return with some of my details. But, later, when I returned, I learned that I was given a different hospital from the one I had chosen. So I collected another form and filled my hospital of choice,” he told HumAngle.

He was sick when this transpired, but he could not access care because of the mix-up.

Delay, unavailable drugs

At the hospital, Emmanuel experienced two types of delay. One was in getting approval before he was attended to; the other was because the prescribed drugs were unavailable.

He was experiencing chest pain and fever. The doctor recommended a Lipid profile test, which helps to assess a person’s cardiovascular risk. Emmanuel was supposed to get a confirmation code from the reception desk before proceeding to the laboratory. In such a situation, what they usually did was send a message to KADCHMA.

“It took about two hours before a response came that it was not covered,” Emmanuel said. So he went to the laboratory to find out how much it would cost and learned that it was up to ₦7,500. “So I said to myself, if they can be deducting ₦1,536.82 from my salary of ₦47,000 every month, then why can’t they cover this for my health?”

There was another test that Emmanuel was required to undertake – it was a chest x-ray, and also an abdominal scan. Fortunately, the insurance policy enabled him to do those. That left out the Lipid test because he could not afford it.

At the pharmacy, Emmanuel was told that the prescribed drugs were unavailable. “When I returned the following day as advised, the pharmacist asked if it was because of that particular drug that I came,” he recalled. “He then asked me if I knew how much the government was remitting to them.”

When Emmanuel learned that KADCHMA remitted about ₦480 (half a dollar) every month per enrollee, he was shocked. “I was surprised and said I can’t blame them because there are drugs they can’t afford to give us. And look at how much they are taking from our salary. So I wouldn’t blame the hospital but the Kaduna State Ministry of Health, because if they pay the amount they are supposed to pay, we would get better treatment.”

The pharmacist then apologised for the unavailability of the drug and promised that it would be available another day. But Emmanuel decided not to go back.

Capitation

The arrangement of periodically paying a fixed amount to healthcare providers per person whether or not they seek care is what is known as capitation. If this amount is too low, it could affect the quality of service rendered by the caregiver.

This was Emmanuel’s experience, which makes him wonder why he has insurance in the first place.

“What I observe is that once they see that you are from a government-run health insurance, they won’t give you effective drugs,” he said. “I found out one of the drugs I was given for ulcer was ₦200. When I went there in September, I was so angry. The doctor prescribed drugs for me, but once I go to the pharmacy and they know I am from KADCHMA, they would give cheap drugs.”

Another time, Emmanuel suffered from a serious headache, so to treat malaria, he was given injections for three days. But there was no improvement afterwards. This makes him draw the conclusion that the drugs were not effective. He also thinks he is given such medication because the insurance scheme pays little.

Emmanuel was employed into the Kaduna State Teachers Board in 2021 but started work in 2023. “When they paid us arrears, they deducted it [health insurance]. About eight months. It was in June 2023 that I started benefitting from health insurance. For me, there’s no benefit.”

For the scheme to be more impactful, Emmanuel suggests that KADCHMA works at remitting at least ₦1,000 to hospitals per head in a month. This way, patients would be given better service. In addition, the scheme should also conduct surveys in hospitals.

Why treatment may prove ‘ineffective’

When HumAngle spoke to Ashmed’s Pharmacist, Peter Philip, he pointed out that patients complaining about the ineffectiveness of medication could be due to several factors. One of these is the lack of adherence to instructions on how to take the medication.

“To enjoy maximum benefit from a drug, a patient may be instructed to take it before or after a meal, or if a drug is concentrated, take it after eight hours,” he explained. This is especially when the medication is meant to tackle an infection.

Philip added that at other times, the reason for a medicine’s ineffectiveness is purely psychological because the patient is used to a particular brand. “He may feel that it isn’t working, while it is working in the real sense.”

But what is the source of Ashmed’s medication?

Philip explained that Ashmed procures its medicines from vendors and representatives — mostly Fidson Pharmaceuticals, whose representatives are in Kaduna.

“We look at quality, safety and affordability. One thing you should look at is if it’s verified by related bodies like NAFDAC. We don’t purchase medication without a NAFDAC number. The expiration date is also important.”

Then they check out the chemical composition, whether or not it has been tampered with. In this way, the hospital ensures the medication is in the right condition before it is approved in its facility.

When administering drugs, Ashmed takes a number of factors into consideration. They are fully aware that there is a limit to which KADCHMA can be able to cover the drugs given to patients under the scheme.

“Most of the patients we have, about 70 per cent, are under an insurance scheme,” Philip said. “It’s a business where you are buying a drug and the scheme itself is unable to cover the cost. So we go for more affordable drugs, generics that are safe and of good quality so we can serve our patients.”

Is increased capitation the solution?

Ashmed’s Finance Manager, Blessing Enagbare, agrees with most of what Philip said. She talks about the efforts put in by the facility to bring in quality drugs.

“There are other companies in India who have made partners here in Nigeria. Buying GMP [Good Manufacturing Practice] is not cheap. It is almost eleven thousand dollars. So I won’t pay $11,000 to bring in trash. I don’t want to lose my money. GMP is a certification for people bringing in medicines. It is a system that ensures products are consistently produced and controlled according to quality standards,” she pointed out.

A drug like chloroquine is restricted, but some patients may insist on it, Blessing explained. The facility tries as much as possible to get products that are not too expensive. “It goes round to all cadres. We have different antimalarials in the market right now. We are looking at generics, not brands. So long the generic is there and good. Let me use the same anti-malaria for instance. If the person has Lonard, they are all Artemether and Lumefantrine,” she said and added that Nigerians have a habit of assessing the packaging of a drug rather than understanding or paying attention to its composition.

Since the scheme became operational in 2019, Blessing said, it has been impactful mainly because the average Kaduna citizen has access to affordable healthcare.

“The scheme is trying, and we only hope it gets better because the price of commodities in the market isn’t as it used to be. Insurance is a win/lose or win/win depending on the situation.”

But what could make Ashmed’s relationship with enrollees and KADCHMA more beneficial? Blessing recommended that although the scheme has tried, “we just hope our capitation and fee for service tariff increases.” This is because, in a month, some patients visit the hospital several times and they cannot be deprived of service.

“Some even come with complicated diabetes or hypertension. And we do most of these under capitation. Let them just add a little to it and we would be good,” she said.

Different strokes for different folks

Rachael (surname withheld), a teacher working with the Kaduna State Ministry of Education, told HumAngle she sees KADCHMA as a scam “because the deduction they do for us in a month is almost ₦2000, but they pay the hospitals ₦400”.

Once, when she had an ulcer attack, she was rushed to the hospital only for the administration to tell her that ulcer was not covered by her insurance company. She had to pay ₦25,000.

“I was angry and stopped going there since then, because, even if I go, they give inferior drugs. I know that because they gave me a drug, a lower version of what was supposed to be a Gestin drug. The drugs don’t work effectively,” she said.

“The hospital’s pharmacist told me that KADCHMA drugs are different. Also, sometimes the state government would not pay them for six months or even a year. But the hospitals maintain the relationship because they consider the government-run HMO a valuable asset.”

Unfortunately, the Kaduna State insurance scheme does not operate a roving plan for enrollees, HumAngle confirmed. A patient only gets to choose a particular hospital. However, one can apply for a change of facility, which becomes effective in a couple of months.

“Right now, I don’t use KADCHMA but my money is still deducted monthly. I go to a place where I know I would be treated well. I don’t have small children that use the HMO; it’s my grandchildren. But now we are not using it,” Rachael said, adding that she is considering switching to Ashmed Specialist Hospital because she has heard good reviews about it.

“I heard that they even do ultrasounds for people. That was how I realised that it depends on the hospital. Some don’t follow whether you are under KADCHMA or not.”

Patience (surname withheld), another teacher, said some hospitals refuse to register under secondary healthcare facilities even though they have all it takes to be secondary centres. “If you need surgery, they would tell you you’re not covered and they would be justified because that’s how they are registered under the scheme.”

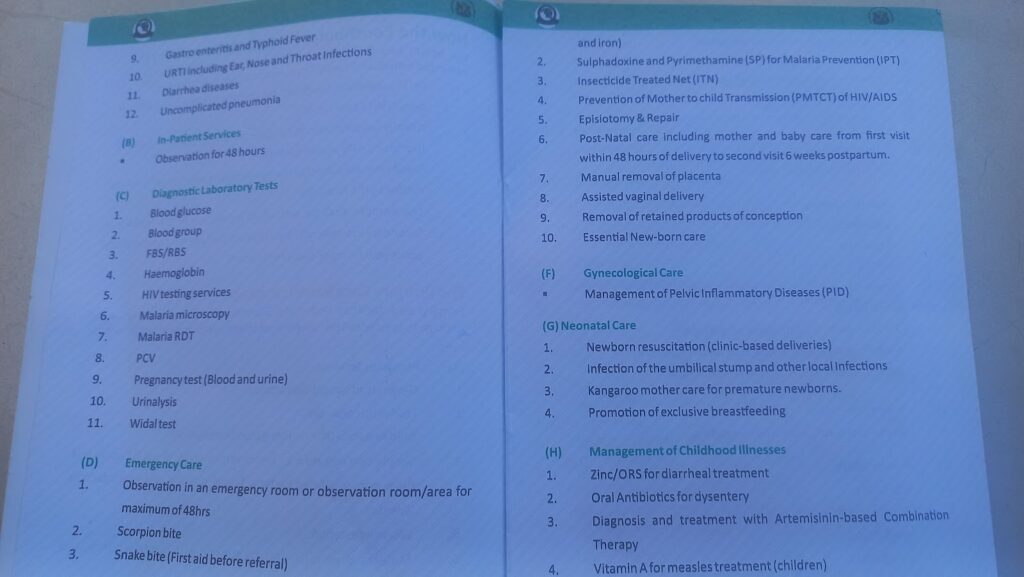

The health benefits package

When enrollees lack knowledge of the scheme’s health benefits package, it makes it possible for some hospitals to deprive them of service, noted Musa Gambo*, an assistant director with the state government.

“If you’re not knowledgeable enough about the treatments you are supposed to enjoy, some hospitals short-change you by telling you that you are not entitled until you pay some money. Meanwhile, if you are informed, you would tell them that it is indeed covered by the state government.”

HumAngle gathered that it is a standing rule between the health scheme and hospitals to display the benefit package in a place where patients can easily view it. Although Harmony Hospital does this, the list is pasted inside the reception area, where only staff have access to. This reporter had to request to view the benefit package.

Sometimes, patients find themselves in situations where they are uncertain whether they are manipulated by the hospital staff or their insurance company is simply ineffective.

This reporter paid ₦2,500 for a stool sample culture at Harmony Hospital, a test that should be covered by the insurance organisation. “They may not give us a reply,” the receptionist said, referring to the process of reaching out to the health maintenance organisation with a request for payment. “They always reply with ‘treat empirically’, which means that the doctor should use his initiative to prescribe drugs. KADCHMA may not approve this stool test, so the doctor should test you for malaria or typhoid some other way. I don’t want to waste your time.”

The scheme’s health benefits package shows that patients are covered for stool and blood tests, among several others. Hepatitis screening is also included.

However, this reporter paid ₦2,000 for Hepatitis screening at Harmony Hospital located in Barnawa, as well as ₦1,000 for every dose of the Hepatitis vaccine.

These services vary, depending on whether the facility is a primary or secondary healthcare centre. Harmony, according to its Managing Director, Elias Anyebe, identifies as both.

Talking further about the need for enrollees to have knowledge of what is in the benefit package, Gambo added that when it comes to blood donation, a patient is entitled to only one pint of blood.

“When my wife gave birth, she was only given one pint and we had to buy the rest,” he said, his response indicative of misunderstandings that could arise from enrollees’ ignorance.

Gambo pointed out that at Rafa Specialist Hospital, they make it clear that they are NHIS and KADCHMA accredited. “Any hospital that is being carried along by the state government knows that it is reputable. This means you are recognised by the state government. It is a plus to the hospitals. That is why it is hard for some of these hospitals to reject KADCHMA’s policies.

“Even when they don’t agree with it, they allow it because it gives them state recognition, and visibility and validates them as a healthcare facility. It enables them to have a high number of beneficiaries. There is also the belief that the government’s relationship with them is permanent unlike private companies. It is also important to them to have a steady income from the government.”

Gambo, like Emmanuel and Rachael, said most hospitals are complaining that the government deducts much from workers but only remits little to them, which can hardly cover patients’ treatment.

Distrust, delay

At some point, KADCHMA began to suspect that the hospitals were short-changing them, Gambo explained. “When a patient goes for a malaria test, they may claim that he or she did something else that requires higher payment. For that reason, they restricted some tests until a request was sent. They also ensure they verify that the patient is indeed an enrollee.”

But this system came with its pitfalls, because sometimes when a request is sent, a whole day may pass without a response, he said.

“It is only when you are familiar with a staffer there that you can call KADCHMA and say a request has been sent, so somebody you know can get back to you. But sometimes, even when a request is granted, it is possible that the patient has already left the hospital and may not be able to go back and access it. So, KADCHMA feels that it’s a way of checking the excesses of the hospitals.”

This was confirmed by HumAngle when we paid ₦4,000 for a scan due to such a delay. It was after about 24 hours that the insurance company sent a code to Harmony Hospital, which then refunded the money.

Fee for service

The KADCHMA programme is arranged in a manner that simulates the NHIS, Anyebe, Harmony Hospital’s MD, said.

“There are services for which one needs to get permission from the HMO, what we call fee for service, and there are services that are direct capitation. So the question of whether it is covered or not does not arise. It is the question of saying if you want to do stool culture, you take permission to have a code and they would tell us to go ahead and do it.”

Responding to the direct payment of ₦2,500 by HumAngle for the stool culture test, the MD said: “When you enter this hospital, we owe you your time and in the services we give you. We want you to have clear information. If I have to reach out to get a code for a particular service, it is good to let you know that there may be a small delay. It is good to be well-informed so that you can be well-positioned to be patient. We cannot tell whether a particular service would be approved or not, till we make the request.”

Anyebe also described the accusation that the hospital gives ineffective drugs as an “immature and juvenile insinuation because we don’t store drugs that are not good.”

He explained that there are grades of drugs that are expensive in the market. “But when you have an equally good substitute that is cheaper, then you give the patient. Even if you come in as a private person, we tell you that this particular drug is available and you have a choice to take it.”

But does a patient under KADCHMA have a choice?

“What I want to assure is that by our agreement with KADCHMA and all other health insurance, we are entitled to treat them. Most people run into a very ugly conclusion if they think we would give them the wrong drugs. That means we are not human. We have to defend that integrity. We are supposed to show compassion,” Anyebe said, adding that patients need to have faith that they will be cared for. When there are certain services not within the coverage of a particular health scheme, the hospital lets its patients know.

“If it is the one that is fee for service, we ask for code. Our motto is compassion, commitment,” he said.

Like Ashmed, Harmony Hospital also gets its drugs from companies such as Fidson Pharmaceuticals and representatives of other manufacturers.

“Remember that we have a large number of workers, and we are all human beings who take drugs. So, the drugs we give for malaria are the ones I am taking. So we make sure we sort and they go through checking,” Anyebe explained.

Some figures

Hassan pointed out that the health insurance scheme was established in 2018 but the government started implementation three years later.

“Its introduction is a shift from the health finance system that exposes people to a significant proportion of out-of-pocket spending and led to catastrophic spending in the past,” he said.

“When you pool resources, you are pooling strength. When you come together as a group, there is power. It enables you to bargain and get what ordinarily one per cent would not get. It is important because when there is a reason for one of us to go to the hospital, the person would be able to pay what ordinarily he would not be able to afford. The pool now becomes his insurance.”

He explained that the scheme is for all residents of Kaduna and not only for government employees.

“Today, we have almost 500,000 enrollees. The breakdown is that when you have over 80,000 staff members, the entitlement includes, for instance, a wife, her husband and four other children.

“Apart from that, there is what we call healthcare provision fund, which is money that comes from the federal government meant to address the vulnerable population in Kaduna State. These include the disabled.

“Kaduna State provided one per cent of unconsolidated revenue to complement the federal government’s efforts. The state government made this contribution to address this same vulnerable population. Under the scheme in Kaduna, we have about 79,000 vulnerable populations that are under the one per cent consolidated revenue. So we have about 500,000 enrollees.”

Since the state’s capitation is about ₦488, Hassan said, if a hospital has 2000 enrollees, what goes to that hospital per month is a pool of ₦976,000 for the people assigned to that hospital. “And because it is a principle of insurance, we pay ahead. So it is a risk-sharing programme.”

The contributory scheme has a benefit package that shows the items under capitation and those paid under secondary requisition. “For example, if we have someone who is on ₦30,000 minimum wage, three per cent is less than ₦2,000. But then the man has a wife and four children, and 488 times six is ₦2,928. And the lower levels are in the majority. But because the principle of insurance is pooling, the man who has more subsidises for the one who has little. The strong subsidises for the weak.”

Since the scheme pays ₦488 per head (principal enrollee) to hospitals, the total amount of monies that goes to hospitals based on the 500,000 enrollees in the state is up to ₦244 million every month. However, the DG pointed out that the number also represents family members benefitting from the programme and not just the principal enrollee, hence it is difficult to achieve accuracy in this calculation.

According to a 2021 report by Premium Times, the number of Kaduna State government employees is not less than 31,401. If, for example, our calculation should go by an average of ₦1,537, the amount deducted from Emmanuel’s salary of ₦47,000, KADCHMA would be pooling a contribution of about ₦48.2 million in a month.

Hassan explained that the scheme has harnessed the formal sector and is working at doing the same in the informal sector. “What we are doing now is trying to address the issues of perception,” he said.

On dissatisfaction

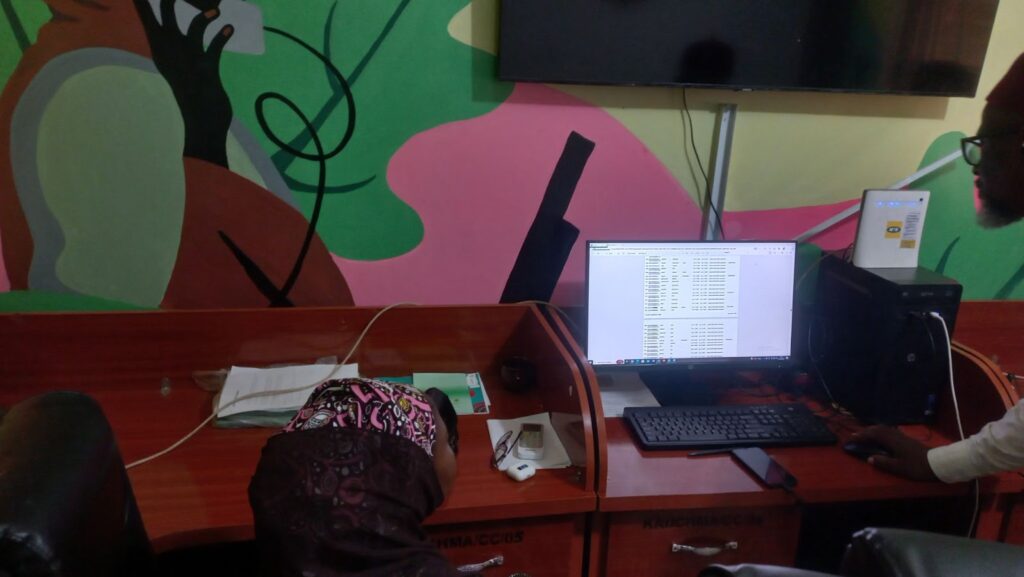

“We encourage our enrollees to report a hospital for issues of misunderstanding, quality or abuse. Situations where they are not satisfied with the performance of a particular service provider. There are measures we take to address such issues,” Hassan told HumAngle in his office in Kaduna.

The KADCHMA building is situated within the Kaduna Ministry of Health complex. It has a customer care centre, where requests are received and reviewed, and an operations room. “We have doctors and physicians who are manning this desk. If you request an item that is outside the package, the doctors will not approve it. This is because the doctors understand what requests should come in and what requests shouldn’t come in.

“Some may tell you the services in that same Harmony Hospital are superb, and another would say they are poor. It is about how you perceive what happens to you,” he said.

He added that one of the major challenges the scheme has sometimes is that enrollees don’t care to understand how the scheme works.

Hassan pointed out that the contributory scheme blocks a lot of shady deals. Once, a patient who was not on the scheme tried to use the identity of an enrollee to access health care. He urged patients who complain about KADCHMA to understand that KADCHMA is just three years old.

“I completely agree,” he said in regards to the delay in responding when hospitals reach out for a code. But he insisted that this changed in 2023, contrary to HumAngle’s investigation.

“When you hear code, that is fee for services that have been obtained – secondary services. When it is done, a claim would be sent to KADCHMA and then we pay. There used to be delays in respect of code, but today, codes are issued in less than ten minutes. We have done this for close to nine months now. We now respond within ten minutes. Through WhatsApp, you can easily get in touch with us. You can also call in.”

The organisation keeps charts of every request, HumAngle gathered. This enables them to know hospitals where bogus claims come from. They also have routine discussions with private providers which they encourage to have staff training in relation to the scheme.

“You cannot have a new employee today and in three weeks another person takes over that desk. If that happens, learning would always have to start all over again,” he said and stressed that it is the rule that hospitals place benefit packages at strategic locations where enrollees can easily view them.

On Nov. 17, 2022, the Federal Government, through the National Bureau of Statistics, launched the results of the 2022 Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) Survey. It showed that, among others, high deprivations are apparent across the country when it comes to healthcare.

The Kaduna State Contributory Management Authority operates a single health plan. Unlike some HMOs, enrollees cannot choose to upgrade in order to access more services. Hassan said this is due to the economic realities of the day.

While some enrollees and hospitals recommend an increase in the monthly payment made to hospitals by the scheme, Hassan suggests a solution that would require workers to pay more. “We are still considering a review to maintain the system and quality of service that enrollees are supposed to get under the scheme,” he said and used Barau Dikko Teaching Hospital as an example.

“The cost of bed space alone is ₦15,000. If your wife is pregnant, she will be treated for all her antenatal issues, and she will give birth. All at the cost of ₦10,050. I think people need to be fair and appreciate the efforts of government.”

*Name with an asterisk was changed to protect the subject’s identity

This report was facilitated by the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism under its Collaborative Media Engagement for Development, Inclusivity and Accountability Project.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.