Despite her successful career steeped in politics, Butler had never held public office and appeared to be relatively unknown to most voters in the state. If Butler had run, she would have faced the monumental challenge of quickly raising the millions of dollars necessary to run a successful campaign in a state as vast as California.

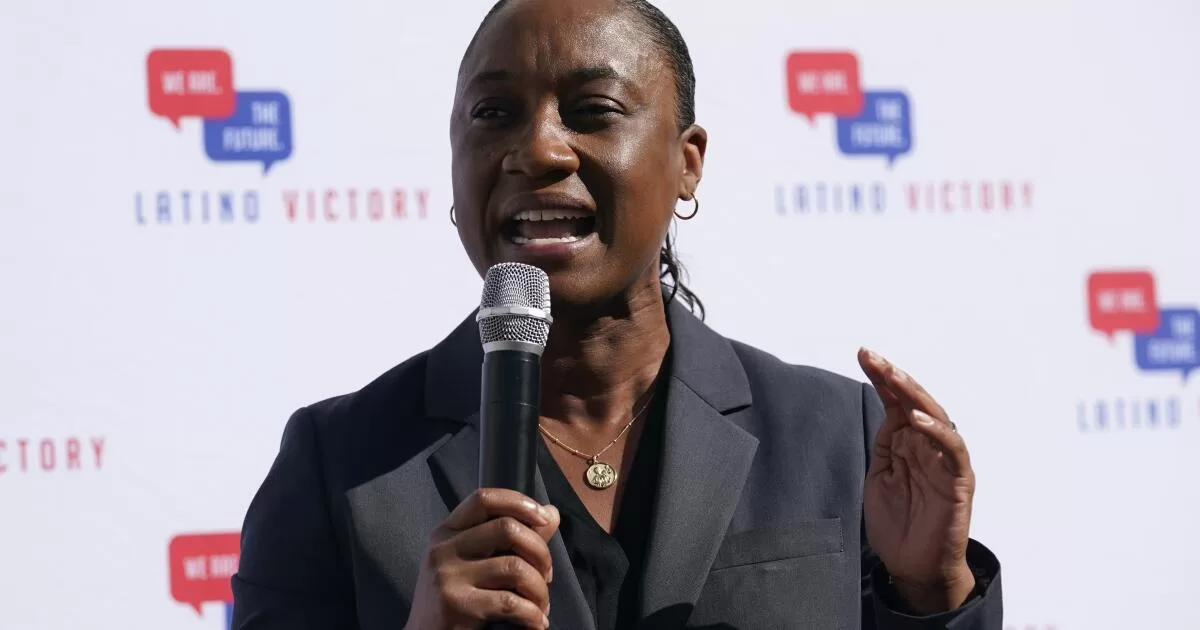

“Knowing you can win a campaign doesn’t always mean you should run a campaign,” Butler said in a statement. “I know this will be a surprise to many because traditionally we don’t see those who have power let it go. It may not be the decision people expected but it’s the right one for me.”

California’s 2024 Senate race already has a crowded field that includes Democratic Reps. Barbara Lee of Oakland, Katie Porter of Irvine and Adam B. Schiff of Burbank, who have all been crisscrossing the state since the winter, courting voters and raising money. Former Dodgers star Steve Garvey, a Republican, also recently said he’s running.

Schiff and Porter are leading in the polls. They have raised the most money in the race, with tens of millions of dollars to spend in the coming months. Because of California’s “jungle primary” system, the two candidates who receive the most votes in the March primary, regardless of political party, will compete in a November runoff.

With the exception of Gov. Gavin Newsom, who appointed Butler to fill Feinstein’s seat, many of the state’s political strategists, donors and influential unions have cast their lot with one of the three most prominent Democratic candidates.

Schiff currently has the support of six statewide labor unions including the United Brotherhood of Carpenters. Schiff and Lee, who is running behind in the polls, have the support of most elected officials in Sacramento and the state’s congressional delegation.

At a recent candidates forum, the trio said they planned to run regardless of Butler’s decision, adding that a competitive race is healthy and benefits voters.

“I think this race has galvanized and energized California to have important conversations about whether we’re getting what we need from Washington,” Porter said.

Feinstein served more than 30 years in the U.S. Senate before her death Sept. 29. Even before she decided not to run for reelection earlier this year, Porter jumped into the race. Schiff and Lee soon followed. Throughout the spring, when Feinstein was missing work because of health issues, the Democratic members of Congress who were running for her seat refrained from criticizing her, simply sending well wishes for her recovery.

Looming over the race was whether Feinstein would complete her entire term — or if Newsom would appoint a replacement. The governor had already filled vacancies for the state’s other Senate seat after Harris was elected vice president, as well as for secretary of state and attorney general.

In those cases, that appointments effectively cleared the field when each appointee ran for a full term. Newsom appeared sensitive to this predicament in the Senate contest, saying in an interview last month that he wouldn’t pick one of the candidates who is running for the seat.

“It would be completely unfair to the Democrats that have worked their tail off,” Newsom said on NBC’s “Meet the Press.”

However, after he appointed Butler, Newsom emphasized that there were no preconditions barring her from running for the seat.

“That’s her decision. And I look forward to her making that decision on her own time,” he told reporters in Los Angeles on Friday. “And I was crystal clear when we discussed [the appointment] that that was not a criteria, that wasn’t a condition and that decision is hers.”

Newsom appointed Butler to fill Feinstein’s seat just days after her death and speculation quickly began about whether Butler would seek the seat in the 2024 election.

Some political strategists questioned whether she would be able to raise enough money to be competitive. While Butler is well known in political circles, she is virtually unknown to most voters in California and would have to spend millions on campaign advertising to change that, an expensive task given that the state has some of the most expensive media markets in the country.

Still, Butler’s ties to two prominent fundraising bases in the Democratic Party could have boosted her prospects.

Butler previously ran Emily’s List, which spends millions of dollars each election cycle supporting female Democratic candidates who favor abortion rights. Earlier, Butler was president of SEIU California — a politically influential union that can provide campaign dollars, door knockers and votes from its 700,000 members in California.

A day after her appointment was announced, Butler told The Times she had “no idea” if she was going to run in the 2024 election, only that she planned to devote her time and energy to serving the people of California.

Newsom put himself in a perilous situation by vowing to name a Black woman to Feinstein’s post if she could not finish her term — a pledge partly driven by frustration over his decision to appoint then-Secretary of State Alex Padilla, one of his longtime confidants, to replace Harris. At the time she was the only Black woman serving in the Senate.

Backed by the Congressional Black Caucus, Lee sought the temporary appointment. She lashed out at Newsom after he said he would not select any candidate who was running for the seat, a move that prompted two Democratic strategists to back away from an independent expenditure committee supporting her bid. After Butler was appointed earlier this month, Lee stood by her side during a ceremonial swearing-in.

California is one of three states that could elect a Black woman to the Senate in 2024. In Delaware, Rep. Lisa Blunt Rochester is running to replace Sen. Tom Carper. In Maryland , Prince George’s County Executive Angela Alsobrooks is running in a Democratic primary to succeed Sen. Ben Cardin.

Times staff writer Laura J. Nelson contributed to this report.