The clock struck midnight and Jummai Abdullahi, a 50-year-old woman from Kuyan Ta Inna, found herself wide awake. Her pregnant daughter, Amina Abdullahi, was in the final stage of labour – the most intense and painful. She needed urgent medical attention.

The nearest clinical facility was the Burji Health Center, a primary healthcare facility located at Burji ward in Madobi Local Government Area, about fifty kilometres from Kano city in Nigeria’s northwest.

As they tried to make their way to the hospital, the struggling primary healthcare centre was waiting to take its toll on the vulnerable mother and her pregnant daughter.

Our research shows that what they found at the hospital is emblematic of the broader issues plaguing primary healthcare in Kano state. Dilapidated infrastructure, understaffing, lack of essential medical equipment, and budgetary constraints have crippled this once-vital community healthcare institution. This situation not only leaves residents, especially in rural areas, without access to crucial medical services but also contributes to rising infectious diseases, preventable illnesses, and maternal and infant mortality rates.

Jummai and her daughter both hopped on a tricycle brought by a neighbour and, in a few minutes, they were in Burji. But as they approached the hospital, there was no one there to admit them.

“The hospital was closed,” she recalled.

Jummai glanced around, her eyes searching for any sign of medical staff, but there was none. Desperation gripped her as she approached the gate again from the inside, but there was no one to attend to them except one person. A lone man who appeared to be a security man.

“My daughter needs help,” Jummai pleaded, her voice trembling. “She’s in labour, and we were told this hospital could assist.”

The man sighed, his eyes filled with exhaustion, and told them there were no doctors on duty at that hour and they would have to wait until morning. The hospital, according to him, operates between 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m.

Amina’s cries of pain grew louder and her mother felt a sense of helplessness that was impossible to ignore. They couldn’t wait until morning; she needed immediate medical attention, but there was none.

With heavy hearts, they returned home, Amina’s agony intensifying with every passing minute. It was a night filled with fear, uncertainty, and suffering. And then, in the poorly lit confines of their humble home, she gave birth to a baby boy, with her mother Jummai and neighbours acting as makeshift midwives.

But the reality of their situation quickly overshadowed the joy of the birth. The baby appeared frail, and Amina herself was clearly unwell. It was evident that something had gone terribly wrong during the birth, something that might have been prevented with timely medical intervention.

At the break of dawn, Jummai rushed back to the Burji Health Center, cradling her fragile grandson in her arms. Inside the hospital, the scene remained bleak. There were only three staff members in the hospital, and only one of them was a medical doctor.

Amina had to wait until 8:00 a.m. and until the doctor finished with those who came before her before she was treated and directed to another hospital for further treatments.

“She is okay now,” her mother said during this interview, which was a few weeks after the ordeal.

“It was really a terrifying experience that can’t be forgotten easily,” she added.

Mallam Ya’u, a resident of the town, says experiences such as the one Amina and her baby went through have become the norm for them because the hospital has long stopped giving the services it was built for.

“The wife of my friend’s son once lost a baby because the clinic in Burji was not working at night and she had to be taken to a hospital in Kwankwaso town,” he said. Adding that before they reached the hospital, she gave birth, and the baby died after a few hours.

“This happened because this hospital wasn’t working. Otherwise, she could have given birth here without complications,” he lamented.

Neglected, In Ruins

Founded in 2008, the once beacon of hope for the community, the Burji Medical Center, now stands as a haunting testament to neglect and decay.

The roofs, long bereft of any maintenance, sagged in resignation, weighed down by the heavy burden of neglect and raindrops. Sunlight streamed through the countless gaps, casting erratic patterns of light and shadow on the abandoned hospital beds with no sofas. Rain has damaged more than half of the roofing in the hospital patient room.

The once-pristine windows, now cracked and stained, allowed only feeble streams of daylight to infiltrate the dim interior. Dust motes danced lazily in the air, caught in the rays of light as they filtered through the tattered curtains that hung askew.

Inside, the medical centre was a small abandoned wasteland. Once-gleaming counters and sterile surfaces were marred by time and a lack of proper care. The shelving units, stripped of medical equipment, stood like silent sentinels, guardians of an empty promise.

The impact of these on the healthcare centre’s staff is distressing. They work tirelessly to provide care under these adverse conditions, but the dilapidated facility hampers their ability to deliver quality healthcare.

Patients who seek medical attention in this facility are often subjected to substandard conditions, with leaky roofs and inadequate sanitation facilities. These deplorable surroundings not only compromise the dignity of patients but also pose serious health risks.

On the website of the Federal Ministry of Health, Burji Health Center offers antenatal and eight other medical services for in and out-patients. But the reality, according to a staff in the hospital who requested anonymity, is that none of the services mentioned get fully done. “It’s just on paper,” he said.

“In ANC (antenatal care), for example, there’s only one staff working, and sometimes the number of patients is so large that she can’t respond to them all,” he explained, adding that even if there’s a will from the few staff they have, they can’t handle the services promised to be given.

The hospital sees an average of 20 patients a day, he said, most of them receiving antenatal care, while a few come for immunization. However, it has no proper maintenance to receive patients in very critical conditions.

Amidst this desolation, only seven staff bear the weight of their roles with a sense of resignation. All of them hailed from distant places.

“And you know, no one can be in someone else’s field,” he explained. “A lab scientist, for example, can’t be a nurse or vice versa. So all of the staff in this health centre are by default the heads of their units,” he added.

“You see, there is some medical equipment here, but what is done with them is entirely not what they are intended for,” the source said.

According to him, the medical equipment is only there for federal supervisors to see so as not to close the hospital, and it is rented to other primary healthcare centres within Madobi LGA when there is knowledge that the inspectors will come from Abuja – the Nigeria’s capital where the headquarter of Ministry of Health is located.

But that’s not the only thing worrying them. Coming every day from a distant location for work, he is looking to see that the government builds staff quarters for them that can help them work closer to their homes.

“There is no home for staff,” he said. “All of us are coming from distant locations,” he added.

Many problems, fewer solutions

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), primary healthcare centres should serve as the first point of access to healthcare for individuals, families, and communities, bringing health services as close as possible to homes and workplaces. It has thus been described as the bedrock of Universal Health Coverage (UHC).

But how did the hospital fall into a deplorable condition? The layers of neglect can be attributed to a combination of budgetary constraints, mismanagement, and a litany of other factors.

Budgetary constraints have, perhaps, been the most insidious factor. A source within the hospital said the centre’s budget allocation has dwindled year after year, leaving it unable to maintain the infrastructure, let alone procure essential medical equipment.

“Even when there is money in the account of the hospital, approval to get things done right becomes very difficult and takes a long time before it can be done,” he said.

Nationwide, the health sector has the highest budgetary allocation but the implementation has become a major problem in the country. In 2023, the budget was increased from 4.7 per cent to 5.75 per cent although lower than the 15 per cent agreed by African leaders.

However, Dr Ibrahim Rayyahi, a medical worker in Kano, has attributed the neglect and lack of funding to the inability of local governments to function as independent entities within the tiers of government in Nigeria.

“The hospitals are supposed to be in the hands of local governments, but the state governments don’t give them their monetary independence, and that has caused lots of issues for funding and management,” Dr Ibrahim Rayyahi, a medical expert in Kano State, said.

Still, some non-governmental organizations conduct some projects in the hospital. At the time of working on this report, there was an ongoing borehole construction project in the hospital by UNICEF.

The NGOs remain the organizations working to make some things work in the hospital, but as one of the hospital staff said, “their funding comes with their problems.” He explained that some projects that are brought to the hospital are not the major needs of the hospital.

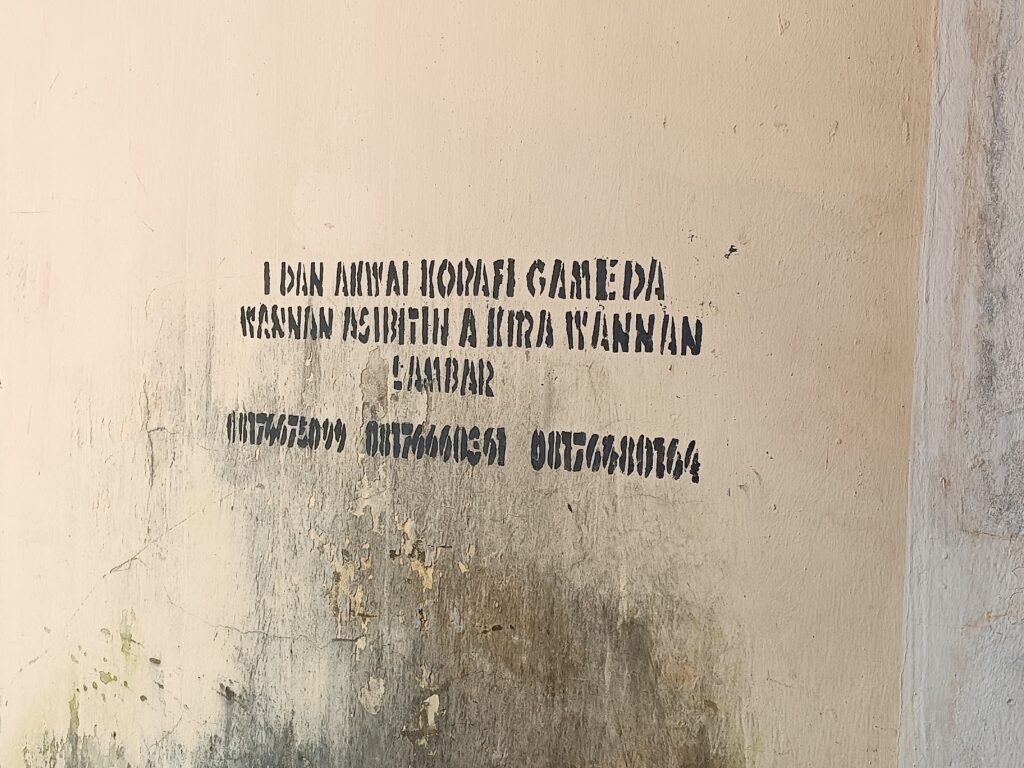

With all these problems, there was a number painted on the wall of the hospital asking patients to call if they faced any problems.

Impact on the Community

The impact of the Burji Medical Center’s neglect extends far beyond its decaying walls. Local residents, many of whom have relied on the centre for generations, are left to bear the brunt of this healthcare crisis.

Residents’ health and well-being are in jeopardy as they grapple with a crumbling healthcare system. With no access to crucial medical services, routine check-ups have become a luxury, and essential treatments are often postponed or foregone entirely.

This has dire consequences for those with chronic conditions and for expectant mothers like Amina, whose harrowing experience became emblematic of the centre’s failures.

Infectious diseases, easily treatable in well-equipped medical facilities, now pose a grave threat to the community. Preventable illnesses are on the rise, and maternal and infant mortality rates are climbing at an alarming rate.

Residents, especially the most vulnerable, are left to fend for themselves or seek care in distant towns, a journey fraught with its own perils.

“You could have malaria in this town but it’s even better to opt for self-medication than to be in a hospital where they’ll tell you they don’t have medicine,” Mallam Saidu Ibrahim said.

Not only Burji

In a state grappling with healthcare disparities, primary healthcare centres (PHCs) are the lifeline for many rural communities. They serve as the first line of defence against preventable diseases, offering crucial services like immunization, maternal care, and basic treatments.

However, the reality in Kano State paints a disturbing picture of non-functional PHCs, despite government promises and investments.

An investigation has revealed that a significant number of PHCs in Kano State remain in a state of disrepair, unable to fulfil their vital role in safeguarding public health. The promise of accessible, quality healthcare for all, especially in rural areas, continues to be elusive.

Our findings indicate that several critical issues are contributing to the sorry state of PHCs in Kano. Primary healthcare centers in Kura, Wudil, and Getso, share similar predicaments.

Many PHCs in Kano exhibit dilapidated facilities creating an inhospitable environment for both healthcare providers and patients. This deteriorating infrastructure directly impacts the quality of care delivered, often deterring healthcare workers from serving in these facilities.

Basic medical equipment such as thermometers, blood pressure monitors, and even essential drugs are often missing in these centres. This critical shortfall undermines the ability of healthcare workers to diagnose and treat common ailments effectively.

Even when facilities are physically intact, the shortage of healthcare workers remains a severe challenge. Overworked and underpaid staff struggle to provide care to the growing population. In many cases, a single health worker must attend to hundreds of patients, resulting in subpar service delivery.

Despite government promises and investments, PHCs in Kano continue to grapple with financial constraints. Mismanagement of funds allocated for healthcare services further exacerbates the problem. Our investigation reveals instances where allocated funds fail to reach the intended facilities, leaving them under-resourced.

The lack of oversight and accountability at both local and state levels allows these problems to persist. The consequences of non-functional PHCs in Kano are dire. Mothers and children are particularly vulnerable, as maternal and infant mortality rates remain alarmingly high due to inadequate prenatal and postnatal care.

Amina has no plans to return to the Burji healthcare centre for deliveries. Her experience had taught her a lesson, but she stated that because it is close to her home, she can return whenever she is ill.

“My baby is fine now,” she explained. “But for me, I still think I can go back when I’m in need of prenatal care, but there’s no reason I’ll go when I’m to give birth again,” she said.

This publication was supported by the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) through Stallion Times under the Collaborative Media Engagement for Development Inclusivity and Accountability Project (CMEDIA) funded by the MacArthur Foundation.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.