The ruling Labor Party last month pushed through a suite of legislation to allow under-18s – including children as young as 10 – to be detained indefinitely in police watch houses, because changes to youth justice laws – including jail for young people who breach bail conditions – mean there are no longer enough spaces in designated youth detention centres to house all those being put behind bars.

The amended bail laws, introduced earlier this year, also required the Human Rights Act to be suspended.

The moves have shocked Queensland Human Rights Commissioner Scott McDougall, who described human rights protections in Australia as “very fragile”, with no laws that apply nationwide.

“We don’t have a National Human Rights Act. Some of our states and territories have human rights protections in legislation. But they’re not constitutionally entrenched so they can be overridden by the parliament,” he told Al Jazeera.

The Queensland Human Rights Act – introduced in 2019 – protects children from being detained in adult prison so it had to be suspended for the government to be able to pass its legislation.

Earlier this year, Australia’s Productivity Commission reported that Queensland had the highest number of children in detention of any Australian state.

Between 2021-2022, the so-called “Sunshine State” recorded a daily average of 287 people in youth detention, compared with 190 in Australia’s most populous state New South Wales, the second highest.

And despite a cost of more than 1,800 Australian dollars ($1,158) to hold each child for a day, more than half the jailed Queensland children are resentenced for new offences within 12 months of their release.

Another report released by the Justice Reform Initiative in November 2022 showed that Queensland’s youth detention numbers had increased by more than 27 percent in seven years.

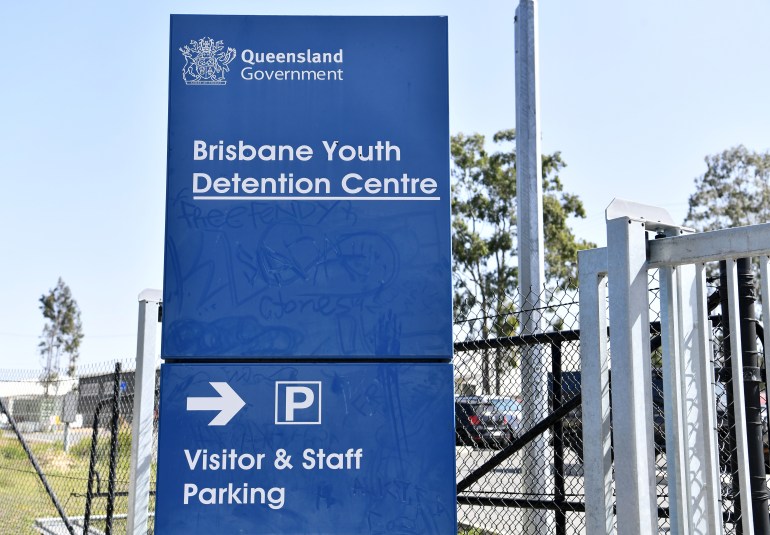

The push to hold children in police watch houses is viewed by the Queensland government as a means to house these growing numbers. Attached to police stations and courts, a watch house contains small, concrete cells with no windows and is normally used only as a “last resort” for adults awaiting court appearances or required to be locked up by police overnight.

However, McDougall said he has “real concerns about irreversible harm being caused to children” detained in police watch houses, which he described as a “concrete box”.

“[A watch house] often has other children in it. There’ll be a toilet that is visible to pretty much anyone,” he said.

“Children do not have access to fresh air or sunlight. And there’s been reported cases of a child who was held for 32 days in a watch house whose hair was falling out. After two to three days in a watch house, a child’s mental health will start to deteriorate. At the point of eight, nine or 10 days in the watch house, I have heard numerous reports of children breaking down at that time.”

He also pointed out that 90 percent of imprisoned children and young people were awaiting trial.

“Queensland has extremely high rates of children in detention being held on remand. So these are children who have not been convicted of an offence,” he told Al Jazeera.

‘Cops and cages’

Despite Indigenous people making up only 4.6 percent of Queensland’s population, Indigenous children make up nearly 63 percent of those in detention.

The rate of incarceration for Indigenous children in Queensland is 33 times the rate of non-Indigenous children.

Maggie Munn, a Gunggari person and National Director of First Nations justice advocacy group Change the Record, told Al Jazeera the move to hold children as young as 10 in adult watch houses was “fundamentally cruel and wrong”.

“It’s incredibly worrying that the Queensland government for the second time this year has suspended human rights laws to punish children, the majority of whom are First Nations kids. What does that say about the human rights our government values?” Munn told Al Jazeera.

“I worry for these kids, what they will be exposed to, how they will be treated and the harm and trauma they will have to work through as a result of this government’s blatant disregard for their rights.”

Munn said there needed to be alternative solutions that would address children’s behaviour without subjecting them to a process that could create more problems.

“There have been countless opportunities for this government to pursue alternatives to incarceration that focus on a child, understanding their behaviour, addressing it and being held accountable outside of a prison cell, and yet these solutions and alternatives continue to be ignored.”

An additional risk for human rights protections is the Queensland parliament, which unusually, has only one house. Without an upper house to scrutinise legislation, the ruling party can pass new laws relatively unchallenged.

Debbie Kilroy, chief executive of Sisters Inside, an independent community organisation based in Queensland that advocates for human rights of women and girls in prison, said that in such a system, the ruling party “can really do anything they want, anytime” without any checks and balances.

“And that’s what they did, for the second time this year, to pass most horrendous laws that are going to perpetrate violence and harm against particularly Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, not only today, tomorrow, next month, but for generations to come,” she said.

Kilroy also told Al Jazeera that the government needed to stop funding “cops and cages” and expressed concern over what she described as the “systemic racism, misogyny, and sexism” of the Queensland Police Service.

In 2019, police officers and other staff were recorded joking about beating and burying Black people and making racist comments about African and Muslim people.

The recordings also captured sexist remarks and an officer joking about a female First Nations prisoner providing sexual favours.

The conversations were recorded in a police watch house, the same detention facilities where Indigenous children can now be held indefinitely.

Australia has repeatedly come under fire at an international level regarding its treatment of children and young people in the criminal justice system.

The United Nations has called repeatedly for Australia to raise the age of criminal responsibility from 10 to the international standard of 14 years old, with the issue highlighted again in the country’s 2021 Universal Periodic Review at the Human Rights Council.

The Queensland Labor government’s suspension of human rights protections – disproportionately affecting Indigenous communities – also comes at a time when their federal counterparts are campaigning for an Indigenous rights referendum.

If successful, the referendum will see an Indigenous advisory board constitutionally established within the federal parliamentary system, known as a “Voice to Parliament”, a signature Labor policy.

“It is rank hypocrisy on the government’s part to push through these cynical, racist laws at the same time they’re campaigning on the Voice to Parliament,” Queensland Greens MP Michael Berkman told Al Jazeera.

“And sadly, there’s nothing in the Voice proposal that would undo these changes or prevent a similarly callous government from doing the same.”

Mark Ryan, Queensland’s minister for police and corrective services, and Di Farmer, Queensland’s minister for youth justice, did not respond to requests for comment.

However, Ryan – who introduced the legislation, which is due to expire in 2026 – is unrepentant, defending his decision last month.

“This government makes no apology for our tough stance on youth crime,” he was quoted as saying in a number of Australian media outlets.