The HBO docuseries “Telemarketers” runs its third and final episode Sunday, bringing to a close one of the most unexpected onscreen journeys in recent memory — from the hard-partying offices of a shady New Jersey call center to the office of a sitting U.S. senator.

Directed by Sam Lipman-Stern and Adam Bhala Lough, the series exposes what’s really behind those seemingly endless phone calls asking for money for various charities, many involving legitimate-sounding police organizations.

Lipman-Stern began working at a phone center as a high-school dropout in the early 2000s, placing fundraising calls for sketchy charities while working for a company called Civic Development Group, or CDG. Very little of the money from those telemarketing calls went to actual charities, though: Upward of 90% went into CDG’s coffers instead.

And as long as employees were bringing in money, they could do whatever they wanted. When Lipman-Stern started bringing a camcorder to work, he captured video of people drinking, doing drugs, pulling pranks and more, all while making lots and lots of fundraising calls.

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

One of his co-workers was Patrick J. Pespas, who was seen as a telemarketing legend for his ability to land donations even as he nodded out from heroin use. It was Pespas who encouraged Lipman-Stern to turn his camera on the company itself and explore how deep these scams went.

Pretty deep, as it turned out.

In the course of the three-episode series, Lipman-Stern and Pespas transform themselves into a dirtbag Woodward and Bernstein, unraveling how the world of telemarketing really works — until sometime in the early 2010s, when Pespas abandoned Lipman-Stern and the project. Lipman-Stern subsequently moved to Los Angeles, where he worked various jobs, including as a videographer shooting weddings, bar mitzvahs and foot fetish videos. Years went by, but his days at CDG and his time with Pespas always lingered in his mind.

“I was always kind of obsessed with the story. I would have dreams about telemarketing, about being back in the CDG office,” said Lipman-Stern. “I always obsessed over it becoming something. When Pat disappeared, it kind of stopped. I always thought maybe one day, maybe before I die, something has to come out, someone’s got to see this stuff. Because it was just so wild.”

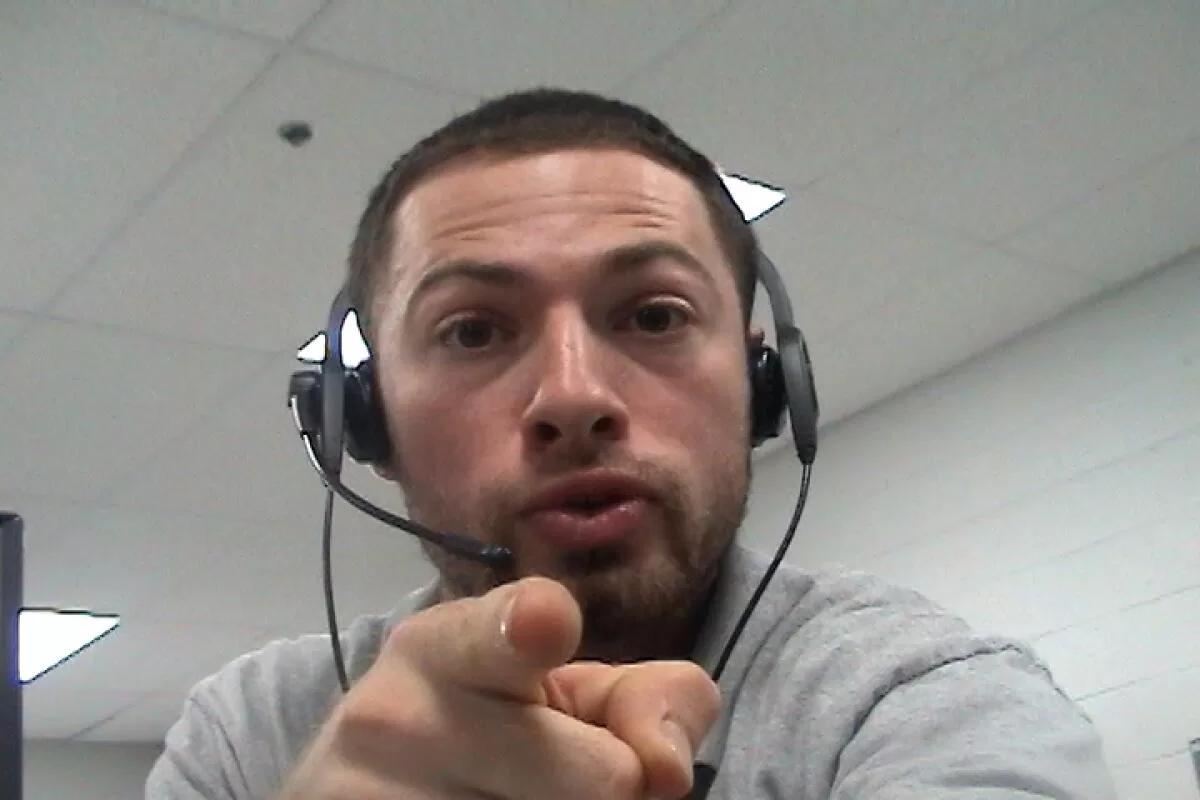

Sam Lipman-Stern in “Telemarketers.”

(HBO)

It was during that break in the project when Lipman-Stern reached out to Bhala Lough, a cousin he didn’t really know who is a documentary filmmaker. The footage of CDG and the investigation of telemarketing scams was intriguing to Bhala Lough, but it was the people, the characters, that really made it special. Bhala Lough had a deal with David Gordon Green and Danny McBride’s production company Rough House Pictures; they came on as executive producers.

Bhala Lough in turn took the project to “Uncut Gems” filmmakers Josh and Benny Safdie. Bhala Lough was initially thinking of them to direct the project — they had previously made the documentary “Lenny Cooke,” which was similarly rooted in archival footage — but they instead also signed on as executive producers through their company Elara Pictures.

It was Safdie who struck on the three-episode structure. The first is rooted most deeply in Lipman-Stern’s old footage of the party days at CDG. The second follows Pespas and Lipman-Stern’s investigation of CDG and a string of imitators that popped up after the Federal Trade Commission shut down the company in 2009, using their research as a lens on the persistent, ever-evolving realm of telemarketing scams. Sunday’s finale, made up mostly of footage shot since production reconvened in 2020, finds Lipman-Stern reunited with Pespas to finish the job.

“We ended up honing in on the buddy movie trope because Pat was such a great character. And Sam was obviously the Robin to his Batman,” said Bhala Lough. “And then the goal was, can we find Pat? When I came onto the project, Sam did not know where Pat was. He was like, ‘The last I heard, Pat was pumping gas on the New Jersey-Pennsylvania border.’ And I was like, ‘Really? That’s awesome. Let’s go find him.’”

Once they found Pespas, they were relieved that he was in a good place, sober and caring for his ailing wife. And he was all in on picking up their investigation right where they’d left off years before.

“You see how happy he is on these investigations,” said Safdie. “The best moment is when his wife says to him, ‘You’re happy, right?’ And he’s like, ‘Oh, it’s the best.’ That little crack and you’re just like, ‘Oh, my God. This is so unbelievable for Pat.’

“The fact that the documentary has to deal with Pat makes you feel really close to him, and then you trust him too,” said Safdie. “You feel like it’s really good for him to do this, and you’re rooting for him.”

In the intervening years, many telemarketing companies had moved from hustling money for charities to fundraising for political action committees, which are governed by even looser regulations. Among the most unnerving moments in the film is when one of the filmmakers receives a robocall during shooting in which the prerecorded voice on the other end of the line is from someone they know to be dead.

“The most surprising thing to all of us was how the scam had evolved in those eight years since we had given up on the investigation,” said Lipman-Stern. “It had evolved into something so much less regulated, so much more Wild West, so much more dystopian.”

Pespas makes for an eccentric detective. At one point, he refuses to get on a plane, causing the entire production to drive cross-country to make a scheduled interview. In another moment, equally heartbreaking and hilarious, Pespas approaches the national head of the Fraternal Order of Police at a convention, hoping to confront him about state and local FOP lodges’ involvement in phone solicitation scams. But Pespas calls the man by the wrong name and the potential interview slips away.

“We just let Pat be Pat,” said Lipman-Stern. “We’re letting it flow naturally, and we’re just documenting everything. I think that was the most important thing. Just document it. All right, he messed up the name. We’re not going to worry about it.”

“I always had this feeling that everything we were getting with Pat on camera was gold,” said Bhala Lough. “I never felt like this is a problem for the show… You see how human Pat is. He’s leading with his heart.

“There’s something beautiful about that, something poetic. Me coming in as the professional documentary filmmaker, I tried to stay out of the way as much as possible. Because what’s special about it is that they’re making this. If you were on CNN or whatever, and you said the guy’s name wrong, you’d be fired. But for me, it’s the exact opposite.”

Patrick J. Pespas in “Telemarketers.”

(HBO)

The ostensible finale of the story comes when Pespas meets with Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.), who has long championed efforts to take on the telemarketing industry. The meeting was in part facilitated by Ann Ravel, onetime chair of the Federal Election Commission and another interview subject in the film.

“When we first started out doing these interviews in Episode 1 with guys inside the [CDG] office, we didn’t know what we were doing at all,” said Lipman-Stern. “All the interviews that he had done kind of culminated in that moment with Sen. Blumenthal. I think that was Pat at his best. We were all really proud of him in that moment because he just came ready. To see his progression from where he started to where he is now, you can see it most in that interview.”

Pespas excitedly begins monologuing at Blumenthal, explaining all that they have uncovered in a breathless rush, as the senator looks increasingly bewildered by the man in front of him.

Blumenthal passes Pespas off to his staff, who in turn quickly end the meeting. A potential moment of action becomes something of an anti-climax. Except for the fact that Pespas and Lipman-Stern had made their way from a grimy New Jersey phone bank to a meeting with a U.S. senator. Regardless of the outcome, that’s an accomplishment in itself.

“We followed up with what they asked for, 80 pages’ worth of documentation of this scam and what we had discovered. We followed up a couple times and never heard back,” said Bhala Lough of the results of the meeting. “We were hoping Sen. Blumenthal was going to kind of vouch for Pat and help get him in front of Congress to testify about this stuff, especially the PAC problem.

“That was our goal. We weren’t just putting on airs or trying to make a scene,” said Bhala Lough. “Because every regulatory body we went to, and we went to all of them, the FTC [Federal Trade Commission], the FEC [Federal Election Commission], the FCC [Federal Communications Commission], the IRS, they all told us the same thing: ‘Congress needs to change the rules.’ We hope that happens. We hope the senator will call us up and be like, ‘I saw the show. Let’s talk.’”

In a statement to The Times, a spokesperson for Blumenthal wrote, “We consistently welcome information and complaints about wrongdoing and consumer abuse. Senator Blumenthal has a long record of leadership on this issue, and we will continue to call for accountability against scammers and telemarketers especially anyone who impersonates nonprofits and charities.”

“It’s the climax of this whole adventure, and it doesn’t end the way you think it should end. It’s like, ‘That kind of went way south,’” said Safdie. “You don’t know what to make of it.”

“Even though it didn’t go perfectly for a normal documentary, this kind of succeeds on the level that they were going to succeed,” he added. “And not only that. They made a movie about it, and now that’s going to do the work they wanted to do in the first place. It’s going to get people aware, and they’re going to start calling their senators and trying to change things. So they did do it.”