“We couldn’t believe it,” an engineer who worked at the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant told Al Jazeera.

“We completely denied it, one can’t just seize a nuclear station, it’s the safest place on the planet.”

On that fateful Friday, sirens that sounded like wounded animals wailed endlessly, and shells flew in the night sky.

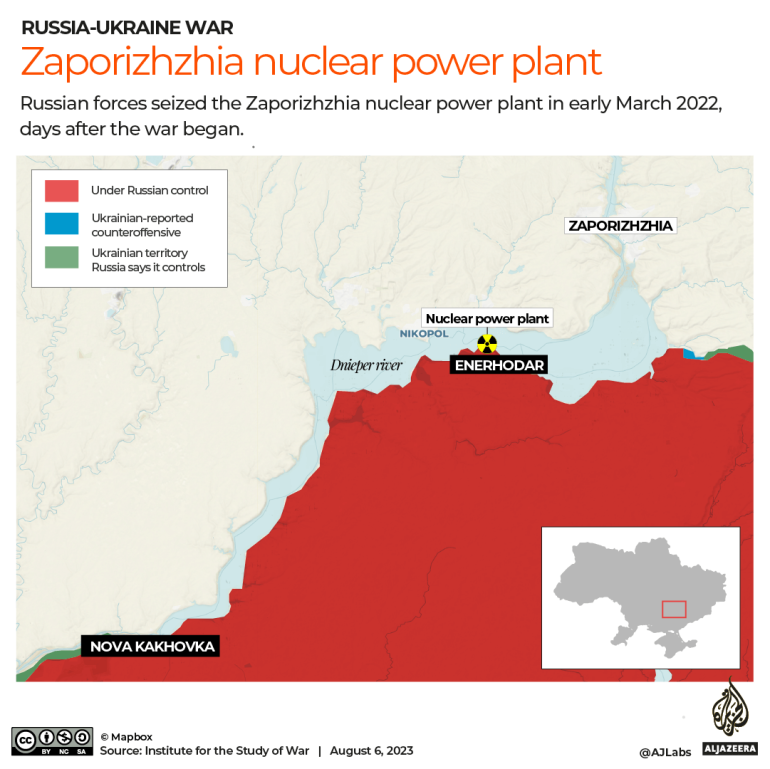

During Moscow’s efforts to seize the power station, which once produced a fifth of Ukraine’s electricity, two Russian tanks barraged the station’s walls with bloodcurdling thuds.

Ukrainian security staffers yelled into a bullhorn for hours to “stop bombing a nuclear site”.

A fire erupted at a station’s training centre and dark plumes of smoke blanketed the forest around the company town, Enerhodar.

Horrified residents began building barricades and blocking entrances into their apartment buildings as armed fighters ran around the town of about 51,000 people.

For this story, Al Jazeera interviewed two engineers and another resident who have since fled Enerhodar but regularly keep in touch with old neighbours and colleagues there.

Amid the takeover, luckily, reactors and spent fuel storage were not hit and radiation levels didn’t spike because Russian “experts consulted these a******s on where they can shoot and where they can’t,” one of the engineers said, referring to pro-Russia Ukrainians.

The worst he and his colleagues feared was a replay of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster.

Encased in protective zirconium, uranium fuel heats the reactor and a water coolant that turns into steam, rotating turbines and generating electricity.

But the casing can melt at a high temperature and start a “para-zirconium reaction” that turns each gram of water into several cubic metres of highly flammable hydrogen.

“Once it has begun, you can’t stop in, it will keep heating up, will heat up itself until everything is blown to freaking pieces,” one of the engineers said.

Thousands have since left Enerhodar.

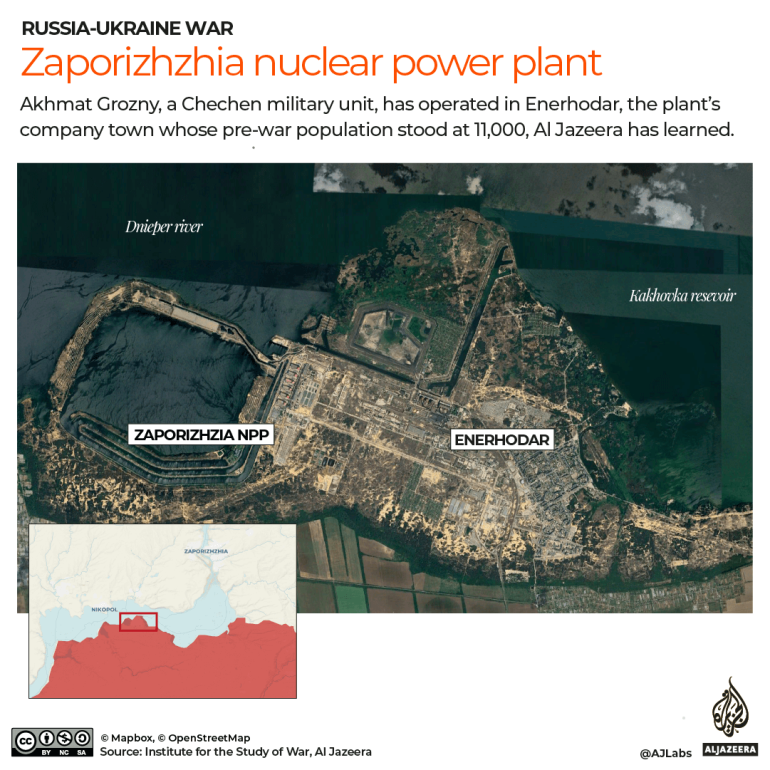

Al Jazeera reported on Wednesday on the feared Chechen unit which polices the occupied Ukrainian nuclear town.

The technicians that signed up to work under Russian occupiers were well rewarded, one of the engineers said, claiming those who remained received two salaries in two currencies – for doing one job for a period.

The occupiers paid workers in the Russian rouble, while they still received the hryvnia from Ukraine’s state nuclear company Energoatom – until it found out about their “volunteer collaboration”, fired them, and stopped transferring wages.

“They felt just like sheikhs,” one of the engineers said.

“All the ladies started getting beauty injections, or doing things they could spend a lot of money on, something you could buy right now.”

The words seem more apt to depict a boomtown amid a gold rush and seem light years away from the realities of the Russian-Ukrainian war – and especially the life in the potential epicentre of a nuclear disaster.

‘The main danger will be new Russian attacks’

In the days and weeks that followed the takeover, Moscow deployed hundreds of servicemen and Chechen national guardsmen to the station.

They arrived with multiple rocket launchers, armoured vehicles, landmines and other weaponry often placed between the station’s blocks or in Soviet-era bunkers.

The Russians shelled Kyiv-controlled areas with impunity knowing Ukrainian forces wouldn’t hit back.

Moscow’s troops wanted to redirect the flow of electricity from Europe’s largest nuclear station to energy-starved Crimea.

But their attempts failed because of damage to high-voltage lines and a Crimean electrical substation, and the complexity of synchronising the station’s output with the Russian power grid.

Because of safety concerns, all of the station’s six reactors have been shut down amid the war.

Most Ukrainians nationwide live in apartments with central heating systems, but as Moscow launched hundreds of cruise missiles and drones this past winter on critical infrastructure, they were deprived of heat, power and water.

The power deficit that led to blackouts and rationing has gradually been compensated by bolstered operations at three other nuclear power stations – and a twofold drop in Ukraine’s industrial production, Oksana Ishchuk, executive director of the Center for Global Studies Strategy XXI, a think tank in Kyiv, told Al Jazeera.

In the coming winter season, when central heating will be badly needed, Ukraine will make do without the power generated by the Zaporizhzhia station, she said, but warned that “the main danger will be new Russian attacks on critical energy infrastructure facilities”.

Money and ‘heroism’

Even though the Zaporizhzhia station does not generate electricity, thousands of staffers are still needed there to monitor its infrastructure and the constant cooling of the reactors.

Aided by Russian servicemen and intelligence officers, Enerhodar’s Moscow-installed “administration” tried sticks and carrots to keep 11,000 Ukrainian staffers at work.

The stick involved abduction, detention and torture, according to Ukrainian officials and employees of the plant.

Even so, “Ukrainians at the power station act with dignity and refuse to cooperate,” Energoatom, a state-run conglomerate in charge of Ukraine’s four nuclear power plants, said in May.

Some workers disappeared without a trace as unmarked graves began dotting the forest.

Hundreds more allegedly spent days, weeks or months in overcrowded cells, sleeping in shifts.

Sometimes, a detainee agreed to falsely “confess” in “directing Ukrainian artillery fire” or “spying” in return for freedom and “clemency”, one of the engineers said.

“You memorise the text, then say it on camera. They release you … Then they publish [a story in pro-Kremlin media outlets] that you are so horrible, but they’re so generous.”

Several, however, agreed to cooperate, because of the carrot – hefty salaries.

Some justified staying by claiming they were “responsible for nuclear safety” one of the engineers said ironically, “that while they’re there, they won’t allow any lawlessness to happen, that they stayed on like heroes”.

And then, there are the pro-Russian Ukrainians.

The older ones feel nostalgic about their Soviet-era youth, others support the Kremlin’s narrative and hold Kyiv responsible for instigating the war.

But their alleged “collaboration” goes beyond simply acceptance of Moscow’s viewpoint.

“They snitch on pro-Ukrainian neighbours, report those who left [the occupied areas] so that Russians can rob their apartments or move in there,” a fugitive Enerhodar resident whose pro-Russian parents stayed behind, told Al Jazeera.

Some 3,500 staffers, or about one in three, are understood to have signed contracts with the Russian state nuclear company Rosatom.

‘A gift of energy’

Enerhodar, whose name means “a gift of energy,” used to be one of Ukraine’s most affluent towns.

Residents had access to quality healthcare, enjoyed discounted trips to the seaside, attended theatre festivals and music shows, and sent their children to sports schools, including a boxing school that produced several national champions.

The bravest ones even enjoyed year-round swimming in two ponds whose water cooled the reactors and never froze in winter.

The ponds were home to tilapia and Asian catfish introduced for “sanitary purposes” – to eat algae and secure the cleanliness of turbines.

The staffers’ incentives were not just monetary.

The importance of nuclear generation rose after the 2014 separatist uprising in the Donbas that largely deprived Ukraine of access to coal for thermal stations.

Two years ago, the station’s reactors were retrofitted and modernised, and churned out electricity at maximum capacity.

“There was plenty of work, but we understood how important it all was,” one of the engineers said.

After the Russian takeover, the town deteriorated.

Residents spent hours in bread lines amid food shortages.

A couple of months later, Moscow-appointed authorities began shipping substandard, pricier foodstuffs from Crimea.

Local entrepreneurs also bootlegged and sold it – along with cigarettes, alcohol and medical drugs – from the boots of their cars.

However, the station’s staffers who agreed to work with Rosatom had plenty of money – especially the older, retired ones who collected pensions and salaries from Kyiv and Moscow while continuing to work.

Russian servicemen and separatists from Donbas allegedly drank too much, and the Moscow-installed “authorities” banned the sale of alcohol, a step that triggered the production of homemade moonshine.

The new lifestyle felt like a throwback to the early 1990s when the newly independent Ukraine adapted to a market economy.

Economically, the situation was even worse than the gradual separation of the rebel-controlled “People’s Republics” in the Donbas.

“The turnover of goods and money is being reoriented towards Russia as there is no communication with Ukraine-controlled areas,” Kyiv-based analyst Aleksey Kushch told Al Jazeera.

The occupation even led to small environmental disasters.

Because the now shut-down reactors no longer produce warm water, the tilapia and Asian catfish in the cooling ponds died and washed ashore.

Then some of the bored occupants began racing their cars on the artificial hills made of soot and other waste from Enerhodar’s thermal power station.

The races cause highly toxic dust to rise and pollute the air, Enerhodar’s exiled Mayor Dmytro Orlov said in mid-July.

A narrow escape

As fighting intensifies, leaving Enerhodar for Kyiv-controlled areas has become next to impossible.

Russian forces have been accused of shelling cars with civilians, blaming their deaths on Ukraine, and supplying lists of the most essential staffers to checkpoints.

Al Jazeera was unable to independently verify these claims. Throughout the war, Moscow has denied targeting civilians.

“The departure is maximally complicated and sometimes it’s simply impossible to leave the occupied areas, especially without money,” one of the engineers said.

He managed to leave by the narrowest of margins.

The man and his family drove via Russia-occupied areas, including the nearly destroyed city of Mariupol, which resembled “pure hell”.

“People sit and drink coffee, the sign [on the building’s] first floor says, ‘a lounge cafeteria,’ but the rest of the building is black, and there are no more floors left,” he said describing a drive through downtown Mariupol.

They entered the southern Russian city of Rostov-on-Don one day before the Wagner mercenary company briefly seized it on May 23.

Then they drove north and west to enter the European Union after an exhausting, hours-long interrogation by Russian intelligence officers, and finally crossed back into Ukraine.

Still on Energoatom’s payroll, the engineer is settling in Kyiv but is ready to leave for Enerhodar once the Russians are pushed out or retreat the way they had left several occupied areas last year.

He compares his rapid-response crew to paratroopers that must move fast to retake the station and prevent a disaster.

“The situation will be critical,” he said.