Just when Zara Buba starts to get comfortable, someone in uniform comes and rips her from her home. It happened one afternoon 11 years ago back in Bama when soldiers burnt her house to the ground. “You can go anywhere; we have finished our job,” they told her as the building’s joints cracked and fell apart.

They did not offer any reason for their action. After months of moving from place to place, losing her husband to hypertension and two children to extrajudicial murders, Zara finally settled in Maiduguri, Borno’s capital city in northeastern Nigeria. She hoped to find safety, stability, and support. The first displacement camp she arrived at turned her away, but she was welcomed when she got to the Dalori II camp. Then, it happened again.

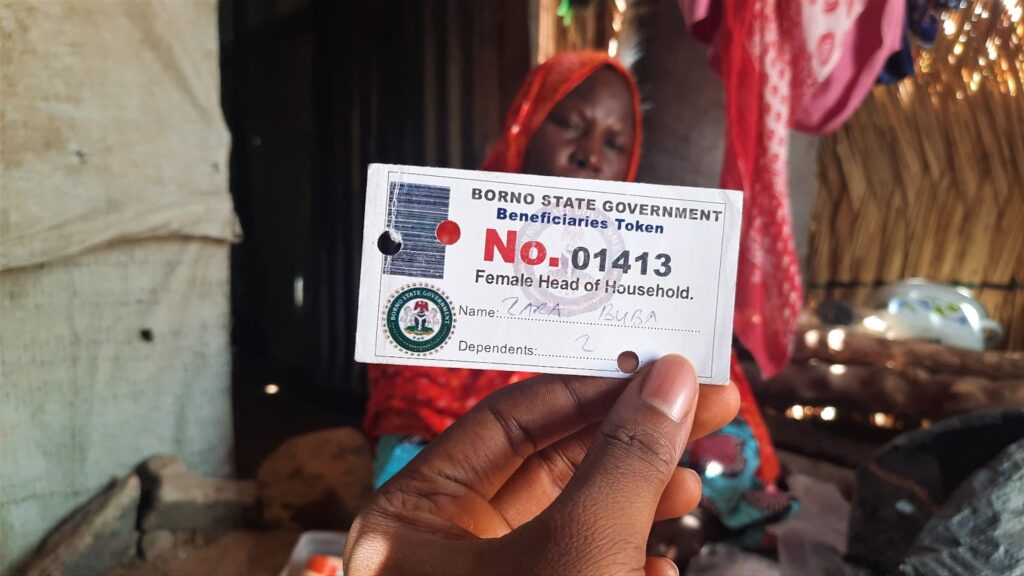

“One night, around 2 a.m., they [camp officials] woke us up. We were frightened, but they told us it was the Governor that came to the camp. I called my daughter to join us. They lined us up into men and women and gave us cards,” she recalls.

The cards, which made them eligible for palliatives, by implication also marked them for eviction from the camp.

After that incident in late June 2021, the IDPs stopped receiving aid. About a year later, the state authorities closed the camp like several others in the capital city. Those who received the cards that night in June were given cash and foodstuff so they could start lives afresh elsewhere, preferably closer to their home communities. The government hoped that by cutting the pipe of humanitarian assistance and resettling the IDPs, they would become more resilient and it would reignite bursts of economic activities in the long-abandoned communities around the state.

But many displaced people do not share in this vision.

Shutting down the camps has meant depriving them of aid and basic services such as affordable healthcare, education, clean water, and decent sanitary facilities. Those who lived in concrete houses are now condemned to sleep in makeshift tents with leaky roofs and muddy floors. Those with businesses no longer have a sizeable population of ready customers. Life has been more brutal in the city since the closures, but many IDPs remain still. For them, Maiduguri is as close to home as anywhere the government might replant their feet outside their ancestral communities — many of which remain unsafe.

With the Boko Haram insurgency, which reared its head in 2009, Nigeria has faced its worst armed conflict since the brutal civil war of the 1960s. Within 12 years, the conflict had directly killed over 35,000 people and indirectly led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands more. Over 2 million people remain displaced in the Northeast and over 330,000 Nigerians have been pushed across the borders to other Lake Chad countries as refugees.

Boko Haram founder Mohammed Yusuf sowed the seeds of the insurgency at the Ibn Taymiyyah Mosque in Maiduguri. When the crisis escalated following Yusuf’s death and security agents and militias clamped down on the insurgents, they relocated their base to the Sambisa forest and spread out to the surrounding local government areas. The tides turned as the capital city became relatively safe while the rest of Borno burned. At one point, the group had a solid grip over half of the LGAs in the state. As Boko Haram unleashed terror in those places, the people who have lived there all their lives flocked towards the state capital for refuge.

Displacement camps sprang up across Maiduguri and in areas around it, such as Konduga and Jere — some of them recognised by the authorities, others informal. Borno hosted the highest number of IDPs in the Northeast and Maiduguri hosted the highest number in Borno. New neighbourhoods emerged on the outskirts as the city expanded rapidly. The United Nations estimated in 2016 that Maiduguri’s population increased from 1 to 2 million people because of the influx of displaced people.

Since at least that same 2016, the Borno state government had hinted at plans to close all the camps. Five years later, it finally took the first steps — starting with the Mogcolis and NYSC camps in May 2021. Last December, it shut down the Gubio camp, which had nearly 23,000 inhabitants, leaving the last-standing major settlement to be the Muna El-Badawi camp with over 51,000 residents.

“I am convinced that better life in rural communities will translate to improvement in security and well-being of our people. What is good for the state capital is good for the remotest community of Borno,” the governor, Babagana Zulum, said last year.

The authorities provided palliatives for the IDPs getting resettled, which included about 20 kg of rice, 20 kg of maize, a carton of spaghetti, a gallon of oil, and kitchen utensils. Women-led households received ₦50,000 while men received ₦100,000 — half paid immediately and the second half promised as a reward if they followed through with the resettlement programme.

Several people told us the donations did not last more than a month. Some, like Bukar Ali, lost the cash to the chaos of fast-moving crowds and had to borrow money to relocate. Some, like Attom Usman and Abubakar Hamza, did not receive any money because they were not inside the camp when the government officials visited to give out cards. “We were outside with some women trying to enter, but the security agents refused to let us in during the distribution that night,” Abubakar recalls. He says those who were left out could be in the hundreds.

Many more displaced people who were promised a second payment after their resettlement say they have not been settled.

Why remain in Maiduguri?

The government’s resettlement programme has not worked out smoothly for various reasons. The housing projects built to accommodate displaced people in some places have limited capacity and so thousands of people moved out of camps in Maiduguri end up rebuilding their tents and living — again — in camp-like structures. Many see no point in the exercise if all it does is move them to a different place that exposes them to the same problems, if not worse. This concern is worsened by the fact that the resettlement sites are oftentimes not the displaced people’s original communities; they are just the local government metropolis or other considerably safe areas closer to home. The IDPs are still strangers in these places.

Zara moved with the rest of the IDPs returning to Soye, a village in Bama, at first. But when she could not find shelter, she returned to Maiduguri. She wasn’t the only one. “There are very few people in towns like Soye. A lot of us went there, but many people eventually came back.”

Abubakar confirms that some of the people initially taken to Bama and Banki got stranded because there were no available houses and farmlands and thought it best to come back.

Those transferred to Soye met no proper shelters, toilets, functioning schools or clinics, or even enough water pumps, according to The New Humanitarian. The area was also insecure. The camp was painfully close to the bush, and Boko Haram militants were known to be present. “They kept talking about the danger, that we shouldn’t leave [any possessions] out in the open,” one of the returnees told TNH. “I thought, ‘These people (the state government) have brought us here to finish us off.’”

The fear for their lives is one of the top reasons a lot of IDPs have chosen to remain in Maiduguri or return after getting resettled. A survey conducted by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in 2022 showed that only 15 per cent of the IDPs at the two Dalori camps thought the security situation in their rural homes had improved. Forty-six per cent thought they had no choice but to go with the resettlement programme and 32 per cent said they planned to move because they weren’t getting humanitarian assistance.

Returnees have suffered terror attacks in various places. Continued hostility from terrorists has prevented people from engaging fully in agricultural and commercial practices, as envisaged by the government.

“I have to stay here because our village is still not safe. But those whose villages are safe can go back,” says Baba Idrissa, 55, who is from Chinene in the Gwoza area.

Attom, who lived in Usmanti, a village around the Sambisa forest area used by terrorists as a hideout, cannot return for the same reason. He had left the community in 2012 with his kinsmen when Boko Haram kept looting their livestock. Two years later, the terrorists followed them to Bama, where they had started to rebuild their lives and then they were forced to flee again towards Maiduguri.

What is home has changed for many displaced people over the years. It is not as simple as where they lived all their lives before the Boko Haram crisis uprooted them or where their parents are from. Sometimes, these places hold memories they would rather not return to. Or they no longer have the qualities, objects, and people that make them worthy of that label: qualities like peace, objects like the houses they grew up in and around, people like their loved ones whose lives were taken violently from them.

Definitely, for Falmata Mele, 40, home is no longer Bama, where she watched terrorists lure her husband out of hiding alongside dozens of other men and massacre them. She has not seen Maidugu Kanyima or his body since the incident.

“I have no one left in Bama,” she mourns. “My mother is dead. Boko Haram killed my brother, and I also lost my daughter. So I’ve decided to stay here.”

It was when she moved to Maiduguri over eight years ago she reunited with her son, whom she assumed had been killed too.

Failing businesses

Since they no longer have a steady supply of aid, IDPs in Maiduguri depend solely on their livelihoods for survival — especially with the authorities clamping down on street begging. But the path to self-sustenance is crooked and laced with thorns.

Just like she did back in Bama, Zara earned a living from frying and selling akara, a local snack made of beans at the Dalori II camp. She also sold cosmetic products. It was how she survived with her 12 children and grandchildren. Now, with the camp closed, she still sells cosmetic products and clothing for women and children. But it is not the same.

Initially, she bought and sold lots of materials. There were over 13,000 IDPs at the camp. The Dalori I camp nearby also had over 7,000. She did not struggle to find customers. The monthly allowance she received from the World Food Programme (WFP) helped her to invest in her business and get significant returns.

“I made about ₦10,000 a month, but now what we get is just for us to eat,” she says. And that is not a lot. She cooks in the morning and eats whatever leftover there is in the afternoon before preparing another meal at night for herself and the children. The last time she did not have to worry about having enough food to eat, she adds, was before her husband’s death a decade ago.

When the camp was still open, Falmata sold kola nuts, groundnuts, and soup ingredients. Having no capital to continue, she had to switch to making and selling moimoi (steamed bean pudding). But what about the cash the government gave them? She replies that she had to pay off her debts with it. “You know they didn’t give us food for over 18 months, and because I had an injury on my hand, I couldn’t make caps. I borrowed money from people to survive.”

You can’t really call what she does now a business. Her only gain from selling moimoi is being able to eat some of the food; breakfast for her and her children. She needs at least ₦2,000 daily to buy firewood, beans, palm oil, and polythene. If she made the mistake of spending the earnings, she would not be able to buy materials to make moimoi the following day.

“The camp was better because there they gave us food,” Falmata reflects. “Now I even have to trek up to 5 km to the bush to get firewood and even then, there’s no market for firewood. Sometimes there’s no market even for the moimoi.”

Aside from providing a pool of patronage, the camps were also a source of products for traders. Attom, who sells grains such as maize, beans, and corn, got some of his goods from farmers in Konduga, Zamarmari, and Subdu Murabe. But he also bought from fellow IDPs who wanted to trade their food aid. His earnings have dropped from an average of ₦55,000 a month to ₦20,000, which is nowhere near what he needs to provide for his family.

It is no longer business as usual for butchers too. Baba Idrissa says he used to slaughter four rams and make ₦50,000 every day. Now the market has withered and he barely sells one ram. He’s gone back to farming to complement his earnings and fend for his large 12-member family.

A lot of the displaced men went into farming after the camps closed. They were able to lease farmlands with as little as ₦4,000 or up to ₦20,000, depending on the size. But many of the investments went to waste or yielded poorly.

Abubakar Hamza had given farming a shot last year when the fortunes of his tea business slumped. The farm, like those of many others, was flooded and he lost all his money — money he could have invested in his tea shop or used to buy foodstuff for his family. The evening HumAngle visited his shop, the only customer who showed up after over an hour was a small boy looking to buy a sachet of water.

Collateral losses

Formal displacement camps in Maiduguri did not just put roofs over people’s heads. They also hosted essential facilities such as schools, clinics, toilets, and NGO offices such as the International Committee of the Red Cross’ family restoration centres. The camps’ closure meant these other facilities were shut too.

Some of the former occupants of the Dalori twin camps now have their children enrolled at a school inside Dalori quarters, a private estate nearby, but only if they can afford to pay. Tuition at the school is only free for those living within the estate, and cheaper options are far away. Attom’s children used to attend classes at the Dalori I camp, but they’ve now dropped out. He says if he had gotten the palliative from the government, he would have been able to enrol them.

Another worrisome development is the lack of affordable healthcare.

“There was free medical care in the camp,” Attom tells us. “Now we go to a clinic in Dalori village, but they don’t have medicine. They only write the prescription and we have to buy the drugs outside.”

Like her late husband, Zara has been diagnosed with high blood pressure. She is supposed to take her medication every day to stay healthy. She says the drug, which lasts for one month, costs only ₦1,300, but she cannot afford it. She has not taken it in eight days. The last time she checked the pharmacy, she realised the price had increased by ₦120.

When the camp was still open, she often got the same drugs for free. If the clinic did not have them, they would refer her to the hospital.

Falmata has the same health challenge. It started when she became displaced and moved to Maiduguri. Like Zara, she doesn’t take the drugs as often as she ought to. Sometimes, Kachalla, her son who is a commercial tricycle operator, gets them for her. Oftentimes, she goes without them. It’s been a month since she had the medication. Without it, the pace of her heartbeat tends to quicken and her chest feels like it is bearing a massive weight. When that happens, she says turning to prayers gives her some relief.

The needs of the displaced people we talked to ranged from educational support for their children to grants for their businesses, food for their families, and better living conditions. All of them miss the old days when they had loads of struggles, but which at least seemed surmountable, days when they didn’t feel like those struggles were theirs alone because the government and other organisations were there to offer support.

For Bukar, his only request is for those channels of support to be reopened.

“Please tell the government to allow the NGOs to assist us so that we can carry out our normal business.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.