The heat from the sun could be felt in the bones.

Katsina city is hot, so hot that it feels like the town is sitting on a pot of boiling liquid. But on the left side of Babbar Ruga road are women clad in hijabs, perching beneath trees that do not provide enough protection from the scorching sun.

With them are babies strapped to their backs, toddlers sitting on their laps, and aluminium bowls glinting in the sun.

Every Wednesday, hundreds of internally displaced people (IDP) in Katsina, the capital city of Katsina state, North West Nigeria, gather there to wait for food handouts. While there are displaced men on the other side, the women outnumber them.

“We sit here from morning– let’s say 9 am, to around 1 pm,” Rashida Haruna, a displaced mother of twins, told HumAngle. “Sometimes we wait till 4 or 5 in the afternoon, waiting to collect our share.”

At quarter past 12, the women began shuffling around, leaving the shade and sitting closer to the highway in anticipation of a green wagon carrying their first meal, and in most cases, their only meal for the day.

Before 1 pm, the green wagon arrived and distribution began. As displaced women struggled to get their share, their children were being shoved and squeezed in between.

Plain rice and beans, served one scoop per person, is what has kept them eagerly waiting. While each of the men on the other side enjoyed their food alone, Rashida only ate a handful of the food, letting her twin daughters finish the rest.

It is the same for the other women.

For the past decade, disputes between farmers and pastoralists have gradually turned into a bloodthirsty war between communities across states in the northwestern region.

The violence has caused many to lose their lives and others to flee their homes in search of safety. This has resulted in one of the worst humanitarian crises in the country.

People that have survived terror attacks usually describe them as vicious, some get uneasy to go into the gory details while others are able to offer a glimpse of what happened amid the chaos. Fareeda, another displaced woman, remembers how women were harassed and raped during these attacks, “some were also kidnapped. Our houses were burnt and they took away our livestock,” she says.

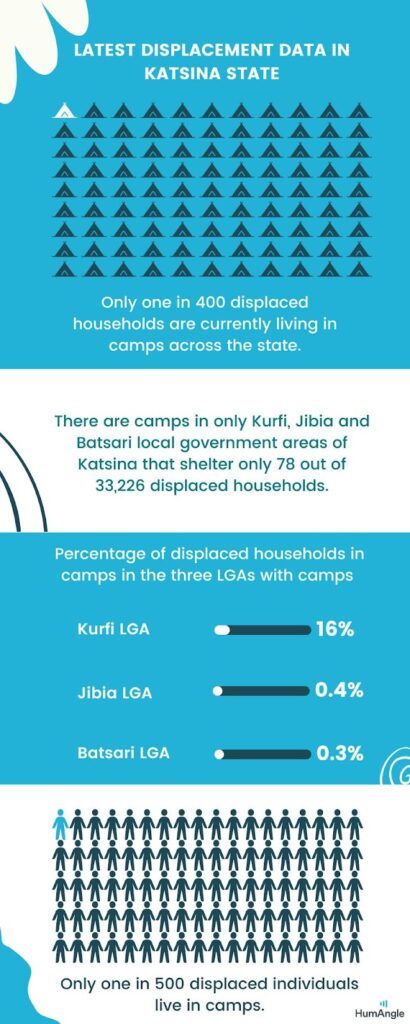

Currently, Katsina accounts for over 250,000 displaced people, the highest in the region, and over 70 per cent of them ran away from armed conflict and incessant kidnappings.

But fleeing from violence does not guarantee displaced families an improved life.

When people run away from conflict, they are known to occupy displacement camps that offer them temporary shelters while relief materials are given to them before they are able to find their footing.

But Katsina state’s authorities have not been willing to consider establishing organised displacement camps that will house IDPs and provide them protection, especially in the capital city which has been the safest so far.

In fact, some of the existing displacement camps in some local government areas (LGAs) were shut down in Nov. 2020. The state government claims that IDPs needed to be reintegrated into their communities to pick up from where they left off.

Currently, all displaced persons in Katsina City are dispersed in abandoned buildings and public facilities such as schools. Some fortunate ones are given rooms that are usually in dilapidated conditions. As displaced families navigate a changed environment, they are hit with a lack of nutritious food, lack of clean water and other necessities and this has resulted in severe health outcomes that are disproportionately affecting women and children.

Salamatu is another displaced woman who fled to Katsina from Bugaje, a community about 30 kilometres away, due to conflict. She said she went into labour while running.

Salamatu was already due to give birth but, “I had not yet,” she says. “I was working on the farm when the attack happened. We ran into the forest to hide and that was when I went into labour. Some of the women helped me find a tree and I pushed my son out. There was no water to bathe or to bathe him for days before we saw some villagers in a settlement that helped us.”

Salamatu was still in postpartum bleeding when she arrived in the city of Katsina without a safe place to go to. “We just went to one of the motorparks to stay, and begged for money. We did this until we had some rent money and got a room in Yar Shanya.” Yar Shanya is a community that hosts displaced persons.

While she is unsure if she currently has any gynaecological conditions, she told HumAngle she feels a burning sensation in her vagina and experiences painful menstruations. This started after she got displaced, she says.

HumAngle presented Salamatu’s symptoms to Dr Fatima Danbatta, an obstetrician. Dr Danbatta posits that these are symptoms of an infection although proper diagnosis is required.

Hunger, Hunger Everywhere

“All of us you see sitting here…” Huraira gestured to the other women scuffling for space beneath the trees as they waited, “…just don’t ask us how hungry we are. Some have not seen a grain of rice in days,” she says in Hausa.

Huraira, 32, is wearing a grey hijab and holding her sleepy 10-month-old daughter across her thighs. “Sometimes we only get food at night and once I share it between my eight children it is gone. I will have to wait until another meal comes.”

In a week, the certainty of getting and eating food comes only twice for Huraira; on Wednesdays and on Sundays afternoons when the rice and beans are donated by Dahiru Mangal –a Katsina-born businessman. Even at that, it is only a few handfuls, Huraira says.

For the rest of the week, Huraira depends on Koko, a runny porridge made with millet flour, or when community members share parts of their meals. On some days, she depends on the money her children might bring home after a day of street begging but on most days she does not get to eat at all.

“The hunger can get so bad that I feel dizzy. I will be seated or lying down but I will see the place spinning. Sometimes I do not even remember where I am,” she explains.

Amid the hunger, Huraira is also nursing a child.

Nursing while hungry leads to constant fatigue and mental strain, Julian Dadzie, a clinical nutritionist at Jos University Teaching Hospital says.

“Breastfeeding is a lot of work, and in the absence of proper food, the mother may not have the energy to keep breastfeeding on demand. This can affect the baby’s growth and development.”

It usually leads to wasting, Julian says. She explains that the little energy the mother gets could go to other activities, “so she won’t be able to breastfeed that child for the amount of time the child is supposed to be breastfed. It is now cut short, and when you’re not giving your baby adequate breast milk the baby is not going to grow according to age.”

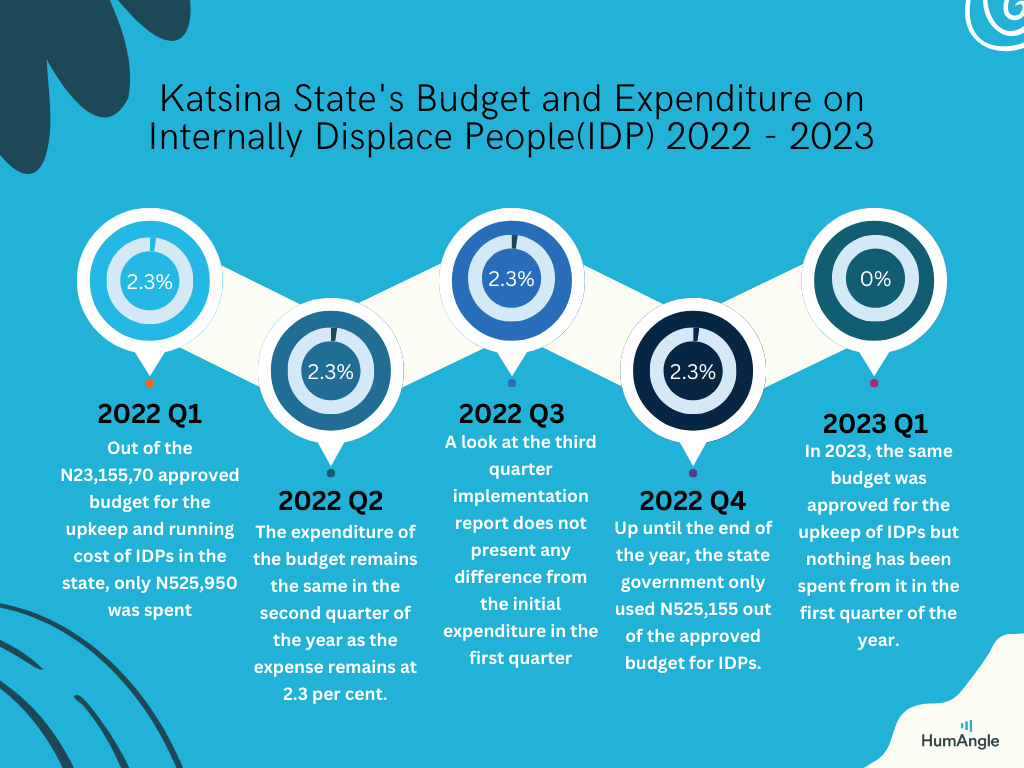

However, as dire as the situation is, there seems to not be expansive expenditure to cater for IDPs’ needs and to improve their living conditions.

Legislative loopholes

There are regulations and policies that guide states’ dealings with displaced people but there are no official legislations passed by the National Assembly that cover internally displaced people. This is a loophole that keeps the government from being held accountable by the law, Barr Peace Adebola, a human rights lawyer, told HumAngle.

“The only legislature that in a way relates to IDPs –in a way– is the National Emergency Management Agency Act [NEMA Act]. That is the only legislation,” Peace notes.

She, however, says even that only provides a vague coverage, “that there should be protection for persons that are internally displaced. It does not break down what the protection should be, how it should be done, and what the government needs to do like the obligation of government and state.”

Although there is a National Policy On Internally Displaced Persons, Peace says it does not have enforceability. “A legislature is passed by the National Assembly but this policy was made by the National Executive Council so it has very very little coercion. Laws have coercion ability, if it is not obeyed you can take it to court but policies have little legal backing.”

The National Policy, however, has a more detailed breakdown of how IDPs should be protected. It also states the roles of humanitarian organisations, the roles of the state government, and even the roles of host communities towards displaced people, “it is very elaborate but it is just a policy guide.”

Resettling of IDPs in areas that are still not safe is also “unlawful,” Peace says. It goes against the Kampala Convention and other international guiding principles, “but due to the lack of expressive laws in Nigeria, it is exploited.”

Breeding a generation of stunted children

When Rashida Haruna, 31, was displaced from her home, she was 6 months pregnant with her twin daughters. Due to the lack of sufficient nutritious food in her body, they had extremely low birth weights when she gave birth to them.

“There is always a high tendency of low birth weight for mothers that do not eat enough,” Julian, the nutritionist, states. “Malnourished mothers do not have enough nutrients to help with the [foetal] development.”

Although low birth weight does not automatically suggest a baby is malnourished, it can gradually lead to that without constant monitoring. At every stage in a child’s life, there is an expected weight that they should have, Julian explains. She adds that it is why in the first six months doctors advise exclusive breastfeeding but that also requires the mother to eat nutritious food.

Malnutrition is not hereditary but it is known to have a domino effect on women and girls.

When a girl-child experiences malnutrition in childhood, and is not given the appropriate treatment and medical attention, her growth into womanhood is stunted as she faces a myriad of physical and mental illnesses. Because of these challenges, she becomes susceptible to complications when she gets pregnant, Julian explains. It is a vicious cycle until it is broken.

Rashida’s twin daughters have been in and out of malnutrition centres. They had just been discharged a day before HumAngle met her, she says, “we spent 9 weeks there getting treated, and this is the third time within one year both of them are being admitted.”

There are several malnutrition centres across the state due to the soaring cases of acute malnutrition. Médecins San Frontierès/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) has described it as ‘catastrophic and a critical emergency.’ Last year, it stated that the organisation’s malnutrition centres across Katsina treated over 100,000 children in seven months.

A community-based acute malnutrition management centre in Batsari LGA also stated that they treat an average of 140 malnourished children in a month. Abdulkadir Yasore, who heads one of the centres, says there are about 8-10 centres in 15 LGAs, and all of them treat an average of 100 to 2oo cases monthly.

These malnutrition centres cater only to children, while women remain malnourished and without medical attention.

Excluded

Although the terrorism and violence in the region has had vast international coverage with several publications in the western media, there has not been any response designed to promote the basic physical and mental well-being of survivors from the international community.

For years now, MSF –a medical humanitarian organisation that has been active in the region– has made several calls to the United Nations and other international organisations to recognise the crises and scale-up their responses and donations to support those affected.

Dr Simba Tirima, MSF’s country director in Nigeria, has stated that in the face of conflict, growing numbers of displaced persons, and unprecedented malnutrition cases, only four humanitarian actors are responding to the crises in comparison with 33 actors presently operating in three states (Borno, Adamawa, Yobe) in the North East.

But the situation of displaced people, especially women and children has remained “a pathetic one,” Nana Ize Musa, a local humanitarian worker, describes it.

Nana Ize, who has worked with Da’awah Family Support, a Katsina-based non-governmental organisation (NGO), stated that although there are local aid actors who have been trying to reduce the gravity of the humanitarian crises in the absence of international response, government authorities have not been supportive.

In 2013, the organisation tried to establish camps for displaced people in ATC and Faskari communities “but the local government focal people were like they don’t want these people there and they should go back to their villages,” Nana Ize told HumAngle.

A decade and a change in government later, nothing seems to improve. Even before camps were shut down, Aminu Masari, the then governor, had banned NGOs from going into camps to assist.

“We know that the fight against bandits and banditry is not over,” Masari said, “but we can handle our displaced persons adequately because we have sufficient food, clothing, shelter, and security for them while we strengthen efforts in restoring security for them to return to their respective homes.”

From 2020 (when camps were closed) to now, there have been continuous abductions and terror attacks across villages in the state. This has led scores of people to run back into some of the closed camps for shelter. Media reports have revealed that IDPs in these camps still suffer from neglect as they face hunger and starvation which has led to deaths.

But this reporter noticed mixed opinions about the situation.

While residents like Nana Ize claim that the government is refusing to acknowledge the gravity of the issue –hence the lack of organised camps and relief materials– some IDPs are being told that the government has been disbursing funds for aid but it is being diverted by corrupt officials.

What the future holds

In 2020, the National Commision For Refugees, Migrants and IDPs (NCFRMI) began constructing a 600-housing unit for IDPs. The housing estate known as “Resettlement City” is said to comprise two-bedroom flats, a primary healthcare facility, education centres, security outposts, worship centres, skill acquisition centres, markets and adjoining farmlands for use by the beneficiaries.

Basheer Muhammed, the then federal commissioner, stated that “the site will house 61,418 persons based on displacement data available to us at the Commission.”

Displacement figures for Katsina in October 2020 was 61,418 but these numbers have more than tripled in the three years since then.

HumAngle tried to reach out to the commission to find out if there would be additional accommodation for the remaining 190,330 IDPs, and to know if there are plans towards ensuring better living outcomes for displaced families who will be resettled but no response was received from the present commissioner, Imaan Suleiman-Ibrahim.

However, through geospatial analysis, HumAngle was able to see the progress of the resettlement site. A satellite photograph roughly shows about 30 buildings in progress at the beginning of 2021, and about 80 completed buildings in March 2023.

On May 29, 2023, the state welcomed a new governor. In his inauguration speech, Gov. Dikko Umar Radda promised to provide peace, and vowed to end violence and other forms of criminalities across the state but there was no mention of improving welfare and providing humanitarian assistance for those already displaced.

He, however, mentions that he will be accountable, “and periodically provide updates on the achievements and challenges of my administration. Your expectations must be rooted in the reality of the state,” he noted.

Peace Adebola, the human rights lawyer, says a comprehensive legislation is needed, “clearly written and clearly focused on internally displaced persons because in the absence of a legislative framework there tends to be lawlessness.”

She also adds that the government needs to acknowledge the problem and remove restrictions on humanitarian aid for IDPs.

“The opinion [those in] government usually have is that when you keep giving them [IDPs] aid, they will not want to go back home, but is their home safe? Let’s assume it is safe, how have you provided for them?

“People have lost their properties and their means of livelihood. They have lost a lot of things due to the conflict and had to relocate. Some have been displaced for close to ten years and you want them to go back. What do you want them to do?”

This report was supported by the Wole Soyinka Center for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) under its Female Reporters’ Leadership Programme (FRLP) ‘Report Women’.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.