Chinese President Xi Jinping announced in April that the study of ‘Xi Jinping Thought’ or ‘Xi Thought’, which encapsulates the vision and ideology of China’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong, would be required study for the bureaucrats, businesspeople, officials, military personnel and many others that make up the tens of millions of members of the CCP.

While such campaigns have a reputation for being dull and uninspiring affairs, this time there is a website, an account on Chinese social media platform WeChat and an app.

The campaign is designed to “use the Party’s new theories to achieve unity in thought, will and action, carry forward the great founding spirit of the Party and see that the whole Party strives in unity to build a modern socialist country in all respects, and advance the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”, according to state news agency Xinhua.

Such campaigns are essential for the central leadership and the accompanying digital tools also provide a way to monitor what people are studying and ensure party members stick with the programme.

Jørgen Delman, a professor of China Studies at the University of Copenhagen, notes such campaigns are often activated after the selection of new party leaders.

While President Xi remains at the centre of the Chinese power structure after gaining an unprecedented third term as general secretary last year, many of those around him were only appointed to their current positions in October and March.

“Additionally, education campaigns are an instrument that the central leadership uses when dissatisfaction arises with the way central party tenets are processed and implemented further down the party ladder,” Delman told Al Jazeera.

But there are also signs that the campaign on Xi Jinping Thought is more than just routine.

Before he left Russia after a three-day visit in March, Xi told President Vladimir Putin in Moscow that “right now there are changes the likes of which we haven’t seen for 100 years.”

According to Andy Mok, a senior research fellow at the Center for China and Globalization in Beijing, the education campaign is meant to prepare the party members for the challenges Beijing expects lie ahead as China rises on the world stage.

“The people have to be prepared to sacrifice,” he told Al Jazeera.

Xi Jinping’s philosophy

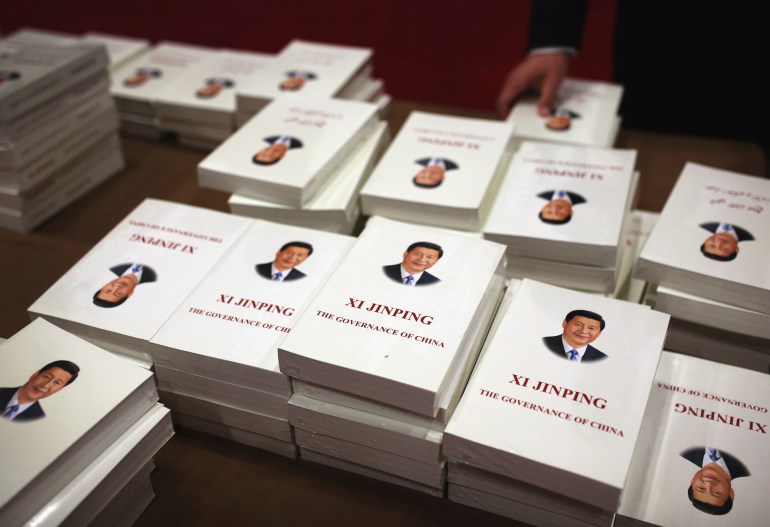

Xi Thought is an ideology mostly pieced together from directives, speeches and writings of the Chinese leader over the years and now encompasses 10 affirmations, 14 commitments and achievements in 13 areas.

It charts the course for China’s journey towards its status as the world’s leading nation – a mark that must be reached before the centennial of the People’s Republic of China in 2049. This is also known as the “rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”, a phrase that has been closely tied with Xi since he first came to power in 2012.

But according to Mok, Xi Thought is more comprehensive than a simple ideology.

“It includes a world view and moral principles that directly translate into what is considered good behaviour,” he told Al Jazeera.

“A more apt comparison would therefore be to a philosophy or a world religion but without the supernatural being.”

Xi Thought was written into the constitution of the CCP in 2017. That was groundbreaking because until that point, only two former Chinese leaders, Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, had had their ideologies written into the party’s constitution.

The philosophy represents both a break and a continuation of previous doctrines.

While the period during Xi’s three predecessors, Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, was marked by more decentralised governance, economic liberalisation and a discreet foreign policy, Xi’s rule has become known for the reverse: centralised governance, broader intervention in the economy and an increasingly assertive foreign policy.

But placed on a longer timeline, Mok points out that Xi’s philosophy is simply the next stage in an ideological development that goes back to Mao Zedong and the Marxist-Leninism with Chinese characteristics that underpins the party.

The full title of Xi Thought similarly signals that it is intended as a continuation of Chinese socialism but adjusted for the 21st century.

According to Xi, some of his philosophy’s more important tenets include: Ensuring the CCP leadership stands above all endeavours in every part of China, adhering to Socialism with Chinese Characteristics with the people as the masters of the country, strengthening the rule of law and the quality of morality of the whole nation, strengthening national security, upholding the CCP’s authority over the army and promoting national unification with regards to Taiwan as well as “one country, two systems” in relation to Hong Kong and Macau.

Xi Thought for the world

Another central aspect of Xi Thought is “promoting the building of a community with a shared future for mankind”, suggesting the philosophy’s vision extends well beyond China’s borders.

The centrality of China has been emphasised in several diplomatic thrusts led by Beijing in recent months.

In May, Xi hosted a summit in the Chinese city of Xian with the leaders of five Central Asian nations.

A primary focus of the summit was to deepen the integration between China and Central Asia and set the stage for further engagement. In a joint statement released at the end of the event, the Chinese phrase “major changes not seen in a century” appeared again.

The summit coincided almost exactly with the G7 summit in Japan. The G7 is a political forum of seven of the world’s leading democracies. China is not a member and was a major topic of discussion for its alleged economic coercion.

A similar pattern played out in March when the CCP hosted a dialogue meeting in Beijing around the same time that the US-led Summit for Democracies was held for a second time.

Thus, geopolitical lines are being drawn at a time of heightened tensions between China and the US.

“This is another likely factor in the timing of the education campaign since the Chinese leadership wants the people to be united in a global struggle against the US,” said Mok.

Too many mandates?

The education campaign also coincides with a new round of anti-corruption investigations.

Crackdowns on corruption have swept through both the private and the public sector during Xi’s presidency and they feature in Xi Thought as a way of ensuring that honesty and integrity are engrained as traits of the party and the country. This time, the hammer fell particularly hard on the bank sector, state-owned companies and Chinese football, with live-streamers potentially being next.

But the heightened focus on philosophy and ideology as well as an intensified anti-corruption drive risks debilitating China’s bureaucracy and enterprises at a time when the country needs effective management to help shake off the effects of the damaging zero-COVID policy, which was abruptly lifted at the end of last year.

“If party members and officials spend a lot of time on ideology and covering their bases to guard against anti-corruption probes, then that takes time away from solving the real practical problems,” explained Delman.

The worst-case scenario would be a modern-day version of the Cultural Revolution.

Mao instigated the Cultural Revolution in 1966 to reinvigorate the party as well as sideline opponents. What followed was a period of shocking brutality as well as political and social upheaval that left at least 500,000 people dead and did not fully end until Mao’s death in 1976. The ideological strife and incessant purges brought the bureaucracy and industries to a standstill.

“No one wants to go back to that,” said Delman.

Another lesson from those years was the damaging effect of the centralisation of power in the hands of one man.

Before the Cultural Revolution, Mao had launched the industrialisation and agricultural modernisation campaign known as the Great Leap Forward, creating a famine that led to the deaths of tens of millions of Chinese.

Now, with the CCP again allowing the concentration of power around one figure, there is a greater risk of bad decision-making, according to Yao Yuan Yeh who teaches Chinese Studies at the University of St Thomas in the US.

“The common denominator among the current CCP leadership is loyalty and deference to President Xi, so there is a risk that these people will tell Xi what he wants to hear instead of what he needs to hear,” said Yeh.

“And if things go wrong economically or politically it becomes increasingly difficult for Xi to blame others when he is the undisputed leader with absolute control.”

To avoid that outcome, the Chinese leadership could perhaps find inspiration in a line from Xi Thought:

“We should be open and frank, take effective measures to address real issues and seek good outcomes.”