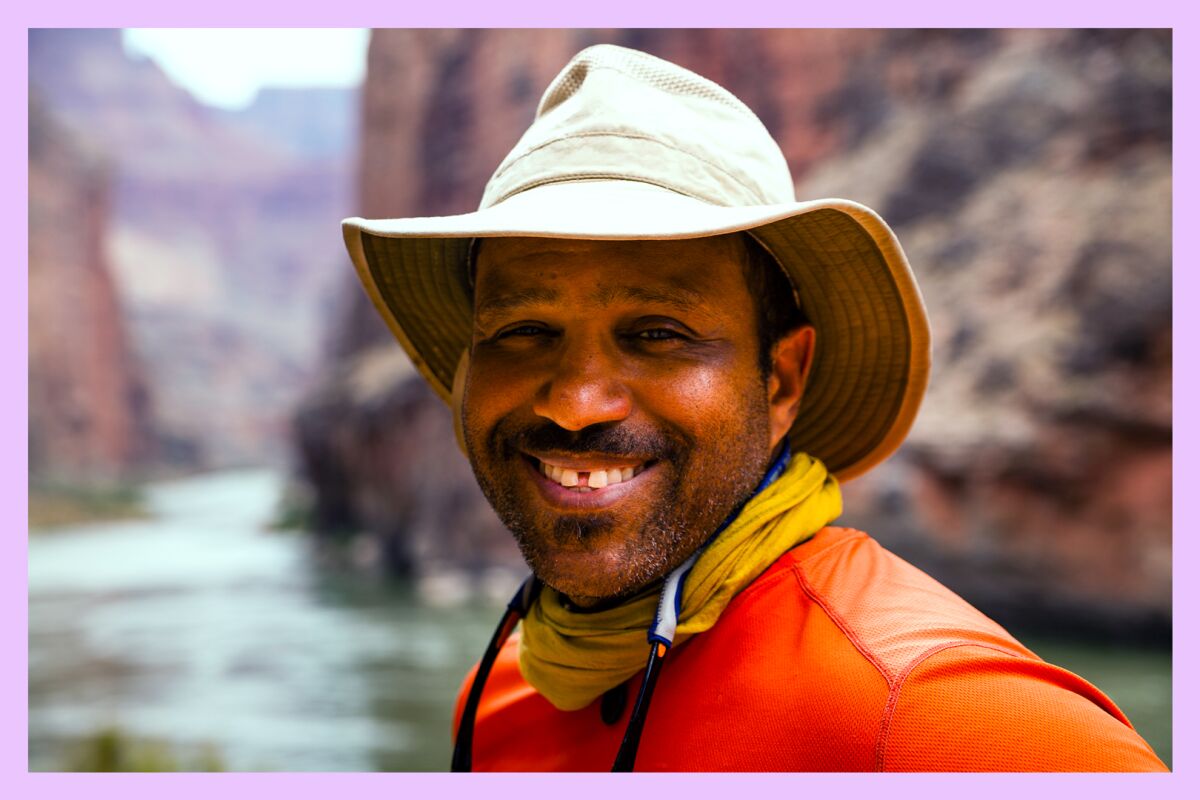

I didn’t know any of these stories until I spoke with James Edward Mills, 56, who started the Joy Trip Project in 2009 to cover the people and culture of the outdoor recreation industry, and to unearth buried stories, especially of adventurers of color.

(Sergio Ballivian)

A Los Angeles native who now lives in Madison, Wisc., Mills is a journalist and author with a long list of outdoor accomplishments. As a backpacking and rock climbing instructor for Cal Adventure at UC Berkeley, Mills has taught his students rope handling, anchor placement, repelling, top roping and multi-pitch lead climbing in Yosemite. In 2016, he was appointed a Yosemite National Park Centennial Ambassador. In 2020, he published “The Adventure Gap: Changing the Face of the Outdoors,” which details the harrowing first Black American attempt to summit Denali by a team of nine. Currently, he’s working on a book project with National Geographic called “Unhidden,” which aims to tell the oft-neglected stories of Black history that are shared at National Park Service monuments, parks, historic sites and battlefields.

Mills is also an expedition expert for National Geographic, visiting national parks with tour groups and sharing stories about Black history; teaches “Outdoors for All,” an undergraduate seminar on diversity, equality and inclusion in the management of public lands at the University of Wisconsin Madison Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies; hosts an online discussion group called the Joy Trip Reading Project; and helped curate an online anti-racism outdoors resource guide hosted by Together Outdoors.

“I go to park managers and say, ‘Hey, look, I found this out and can help tell the story,’” Mills explained.

(Nick Berard)

I chatted with him about his crucial role in unearthing the hidden histories of Black adventurers.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Newsletter

Get The Wild newsletter.

The essential weekly guide to enjoying the outdoors in Southern California. Insider tips on the best of our beaches, trails, parks, deserts, forests and mountains.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

I always thought Sir Edmund Hillary was the first person who climbed Everest, and I never thought about Tenzing Norgay, the sherpa who led him there. How can journalists help decolonize outdoor recreation history in a deep and significant way?

As journalists, our job is to look deeper than the stories that we’ve been told to believe are true. Of course, Sir Edmund Hillary, the guy from New Zealand visiting Nepal for the first time, isn’t going to be able to successfully navigate the Himalayas by himself. But the historic narrative we always tell ourselves is that white men can do anything, and they don’t need the assistance of Native people or the ancestral memory of people who have been in a region for time immemorial.

Buffalo Soldiers were Black servicemen who served as some of our very first park rangers.

(National Park Service)

There are so many stories, from the Buffalo Soldiers to the Black paratroopers of the 555th Battalion. We’re all familiar with the Lewis and Clark expedition, but not many people know that William Clark brought an enslaved person by the name of York who was the principal figure in that expedition and saved Clark’s life at least three times on the expedition. He, as a person of color, was able to establish relationships with Native people here, and was ultimately the first Black person to make it to the Pacific Ocean. We need to make sure that as we’re telling these stories, we’re doing it in a way that is comprehensive and not limiting the narrative to things convenient to what we believe in.

How did getting into the outdoors happen for you?

As a kid, I was a member of Troop 10, which was and probably still is the oldest Boy Scout troop west of the Mississippi. We went hiking and climbing and camping and skiing every weekend from the time I was 9 years old until I graduated high school at 17.

Mills grew up spending time in the outdoors.

(From James Edward Mills)

Plus, my dad was the first Black city councilman in Los Angeles, so I grew up with a lot of privilege. And despite the fact that he and my mom were more active in the civil rights movement, they also like to camp, which is something we did as a family. I remember going winter camping for the first time. We were taking the Palm Springs Aerial Tramway to Mount San Jacinto, and while everyone else is going for hiking, we’ve got tents and sleeping bags and snowshoes — to do that as a 14-year-old, to literally be able to sleep under a blanket of stars and see the Milky Way galaxy, was pretty amazing.

How did you come to focus on increasing access for adventurers of color and telling their stories?

When I started my professional career in the late ‘80s, early ‘90s, working for companies in the outdoor recreation industry — like REI, back when they only had small stores, and then North Face as their first Black regional sales representative — there was a ridiculously low number of people of color involved in outdoor recreation. Back then, I thought the solution was going to be market-based. I was told back then that Black people just aren’t our market.

I decided the only way any substantive change was going to be made was if I made a career shift into journalism and started trying to tell more stories about people of color and the roles we’ve always played in the outdoor recreation and environmental conservation movement.

Charles Madison Crenchaw, left, was the first Black American to reach the summit ofDenali. Matthew Henson, a Black man from Baltimore, was the first person to reach the North Pole.

(James Edward Mills / National Geographic)

Tell me about your book “The Adventure Gap.”

The book is about the first Black American ascent of Denali, the highest peak in North America, in the summer of 2013. From that, I basically tell the story of how people of color have played a role in the creation of the modern adventure era. That includes the National Park System. The Buffalo Soldiers served in Yellowstone in the 1890s and at Yosemite in 1899, 1903 and 1904. The first person to reach the North Pole, in 1909, was a Black man from Baltimore named Matthew Henson. In 1964, within a week of the signing of the Civil Rights Act, Charles Madison Crenchaw was the first Black American to reach the summit of Mount McKinley, what we now formally call Denali. Despite that heritage and legacy, there is a pretty significant disparity in terms of the relative representation relative to our percentage of the population. Black Americans are less likely than our white counterparts to spend time in nature, and I talk about how we got to that place.

Tell me about the historical reasons for that, the oppression that happened.

President Woodrow Wilson brought the policies of Jim Crow segregation and injected them into the federal government, segregating the newly designated National Park Service in 1916. It wasn’t until 1963 that the first Black men were recruited specifically to be national park rangers. It’s really only in my generation and in the generation that follows that you have outdoor recreation for people of color that is free of legal segregation.

“It’s really only in my generation and in the generation that follows that you have outdoor recreation for people of color that is free of legal segregation,” said Mills.

(National Park Service)

But you have the added problem of social segregation. If I roll up into a campsite, unless you actually throw rocks at me or assault me in some way, there’s nothing law enforcement can do to make me feel better about the fact that I’m camped next to a group of people who are yelling racial epithets, or giving me dirty looks, or telling me these are places I can’t go and things I can’t do. And that happened, you know, almost as a matter of course, up until I was a kid. I’m grateful to have not experienced much of that, especially in Southern California. But that wasn’t the case in many other parts of the country.

And then you have a lot of other things that make it complicated. But things are changing. Growth and proliferation of urban climbing gyms are a gateway to expose people to a physical activity like rock climbing, and can be translated to an outdoor recreation area — perhaps but not necessarily to a national park, but a gateway experience. Brands are starting to use Black athletes and models, showcasing them in a way that’s reflective of a demographic they’ve not done before, and people of color are starting to see themselves. Black folks are camping, skiing and climbing together, creating infrastructure and networks of mutual inclusion, so that now a person can go into the outdoors and not be the only one.

There are so many stories to be told about people of color in America and how they’ve invented things, advanced space exploration, pioneered the outdoors — you have your hands full as far as projects and stories.

I go to my editor every week saying “Look, I found another one.” I asked the director at Joshua Tree National Park about the Black history of Joshua Tree and was told there wasn’t any. That evening, I Googled and found a 1902 book about Black pioneers from L.A. who came to Joshua Tree to homestead. There is a rich history of people of color in Joshua Tree, but even the National Park Service doesn’t know or care enough to look for it. That’s where I come in — I go to park managers and say, “Hey, look, I found this out and can help tell the story.”

3 things to do

Don’t miss Herb Club LA’s Mother’s Day herb walk and picnic.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

1. Celebrate Mother’s Day with foraging and a picnic. Celebrate your mama at Herb Club LA‘s herb walk and picnic on Sunday, May 14, from 11 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. at Hahamongna Watershed Park in Pasadena. A picnic by Farmfluence will feature organic and regenerative foods including Smallhold mushrooms, stuffed dates, bean salad, organic sourdough and a peppermint and rose mocktail. Bring a notepad, pen, hat, water and mug. Dress in warm layers. Hiking boots or appropriate footwear is recommended. Tickets cost $30 (for single tickets) or $50 (for those bringing Mom) and are required.

You’ll see incredible gardens like these on the Mary Lou Heard Memorial Garden Tour this weekend.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

2. Tour some of Orange County’s finest gardens. From elegant Tuscan and Japanese gardens to drought-tolerant landscapes as well as coastal scrub and humble cottage gardens, you’ll see it all during the Mary Lou Heard Memorial Garden Tour on May 6 and 7 from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Heard was a passionate gardener and the owner of Westminster nursery Heard’s Country Gardens who in 1993 started a garden tour she aimed to be for and by real people, a tour “for the rest of us.” The yearly, self-guided charity event draws hundreds to gardens big and small to raise funds for the Sheepfold, a shelter for women in crisis and their children. The event is free, but jars are located at each host garden for cash or check donations, or online. No registration is required.

Keep an eye out for birds on Sunday walks with the Santa Monica Bay Audubon Society.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

3. Scope terns, hummingbirds and California towhees at Malibu Lagoon. Join the Santa Monica Bay Audubon Society on the fourth Sunday of every month at 8:30 a.m. for a two- to three-hour adult bird walk for both beginners and experts. (Species range in number from 40 in June to 60 to 75 during migrations and winter.) Meet at the metal-shaded viewing area next to the parking lot and begin walking east toward the lagoon. Spy shorebirds on offshore rocks and above the ocean. At 10 a.m., kids can join in for a one-hour birdwalk. Dress in layers, wear a hat, bring a water bottle and wear subtle colors. Park at the lagoon lot at the intersection of Pacific Coast Highway and Cross Creek Road (costs range from $3 for one hour to $12 for all day) and look for the folks wearing binoculars. You can also park (read the signs carefully) along PCH west of Cross Creek Road, on Cross Creek Road or on Civic Center Way north (inland) of the shopping center.

The must-read

The Recreation for All Act is a bipartisan bill that aims to get more kids outdoors.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Getting kids active outdoors can have some pretty impressive benefits, from combating mental health issues to boosting academic performance. On April 27, Sens. Maria Cantwell (D-Wash.) and Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) introduced the Recreation for All Act, a bipartisan bill that aims to get more kids outdoors. The worthy cause would help bring underserved kids outdoors; pioneer new technologies to track the number and type of recreational visitors to federal land; and require land management agencies to improve their online communication to visitors about road and trail closures.

The bill will be voted on by the members of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee later this month. Read the full text here, and consider supporting it by contacting your U.S. senators here.

Happy adventuring,

Check out “The Times” podcast for essential news and more.

These days, waking up to current events can be, well, daunting. If you’re seeking a more balanced news diet, “The Times” podcast is for you. Gustavo Arellano, along with a diverse set of reporters from the award-winning L.A. Times newsroom, delivers the most interesting stories from the Los Angeles Times every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Listen and subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

P.S.

Take a ride across the Taylor Yard Bridge this weekend.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

What’s a better reward for riding miles and miles in the heat than a cold lager and a hot bite? If you happen to be cycling the L.A. River through Elysian Valley (aka Frogtown), stop by Spoke Bicycle Cafe for snacks and drinks. You can also rent a bike there for a foray and then make an afternoon of it, visiting Suay Sew Shop to browse their unique hand-sewn clothes (or to drop your clothes off for their community dye bath), stopping for lunch at Wax Paper and then heading back for a frosty beer back at the Spoke garden, or at Frogtown Brewery. For dinner, try comforting pastas and burgers at Lingua Franca; tacos and cocktails at Salazar; or tostadas and oysters at Loreto.

For more insider tips on Southern California’s beaches, trails and parks, check out past editions of The Wild. And to view this newsletter in your browser, click here.