With professional and personal ties to the country, Azbel tried to find out if their friends and coworkers were all safe. They soon connected with one colleague, Olena Chernova, who was still in Kyiv.

A public healthcare researcher who has lived in Berlin for 10 years, they told Al Jazeera by phone, “It was a really disturbing, scary time. I was concerned for Olena’s safety. I managed to convince her to come to Berlin and she arrived one evening in late March, with just a small backpack. My young child, who is not very cuddly at all, hugged her. Today, she is part of our family.”

During the past year, Azbel, 36, has hosted nine Ukrainians in the two homes they and their family own in the German capital, including a family of four with two dogs who stayed for a week.

“They arrived in the initial days so managed to find housing quickly. They are a very sweet family and we have had them over for dinner since then.”

They have also supported people with finding accommodation and securing kindergarten places.

And Ukrainians in Berlin are finding some positives in a difficult situation.

“One mother recalled being on an underground train and her daughter being surrounded by all these different characters. She says she was excited about her daughter seeing this diversity from a very young age,” said Azbel, who plans to keep supporting those who are displaced in Germany.

Differing experiences

But for Morgan Rodrick, a 49-year-old software engineer also in the German capital, his experience played out differently.

In the early days of the war, Rodrick was introduced to a man he knew as Sergey through another friend who had been hosting him.

Anticipating a brief stay, Rodrick invited Sergey to stay in his home while he temporarily moved to his partner’s flat.

Rodrick and his partner tried to help Sergey register as a refugee and find his feet in the city.

Two weeks turned into more than a month, and while the longer stay was not an issue for Rodrick, he encountered a few challenges in his attempts to support Sergey during his stay.

“My initial assumption was that he would stay for a couple of weeks within which he would get enrolled in an official refugee programme,” he told Al Jazeera.

“We tried to help him understand some of the official things using Google translate, since everything was in German. And during that, it became clear to us that he didn’t want to be officially registered or known as a refugee. He saw himself as a businessman who just got himself out of harm’s way for a while, hoping to go back to Ukraine shortly after.”

Without registering in the city as a refugee, Sergey was unable to access economic assistance or find work officially, so Rodrick tried to help.

“I was planning to put him in touch with someone who could offer him work as a driver but after having a conversation with him about the work, it became clear to me that he has, what I would describe, as some very old-world values towards women.

“Since the friend that might have had some work for him was a woman, my partner and I realised that this may not go well, so we didn’t end up connecting them.”

Rodrick soon needed to return home for work purposes, and gave Sergey some notice about his plan.

“He came back to get some stuff, as well as the bag I packed for him, and then left. We have not heard from since, it seems like he has disappeared into the world.”

Outpouring of help for those fleeing

Rodrick and Azbel’s varying experiences speak more widely to the different ways support for refugees in neighbouring nations has evolved.

As the conflict began, there was an outpouring of support.

Poles opened their doors to Ukrainians while Germany’s national railway transported Ukrainian passengers free of charge.

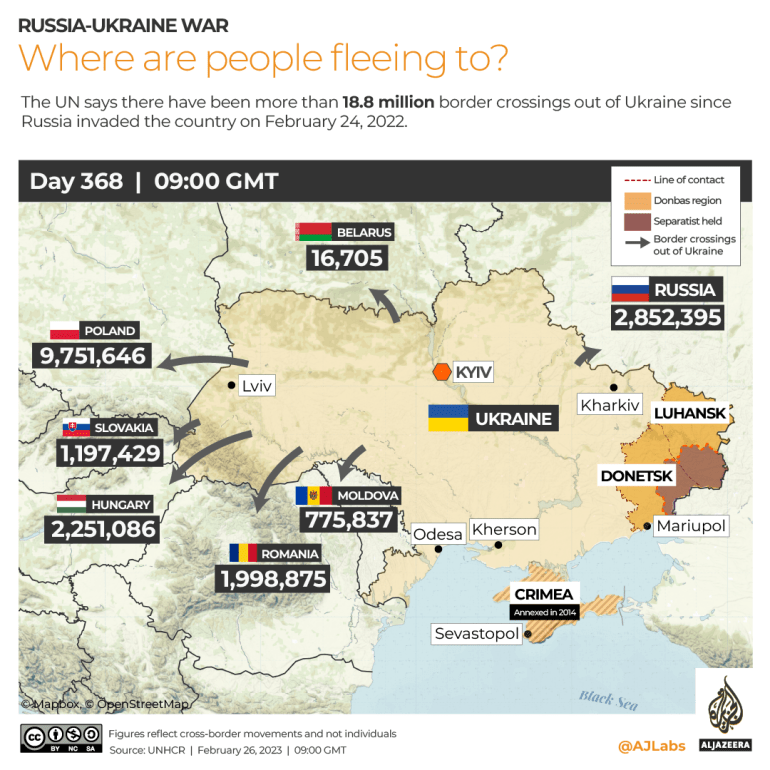

Nearly 19 million people have crossed the border into other countries, particularly Poland, Russia and Hungary. More than one million refugees from Ukraine have been recorded in Germany.

Yet the war has come at a cost for European citizens, who have seen energy prices increase to more than double in some households alongside other rising living costs amid record-level inflation figures.

Germany’s decision, albeit reluctantly, to involve itself militarily by giving Ukraine two of its tanks in January also drew protests.

Despite the economic toll, have polls suggested that, although support for Ukrainian refugees has dropped slightly, it has remained high in the West.

One global survey carried out by Ipsos in January in nearly 30 nations, including the US, Germany, Poland, the United Kingdom, Hungry and France, found despite a dip in support for welcoming refugees in Germany and Belgium, most Westerners still supported taking them in.

Gabrielė Valodskaite, a programme assistant for the wider Europe area for the European Council for Foreign Relations in Berlin, said the commitment is “still there, but maybe it is less visible”.

“Now the support is rather steady, more institutionalised, and more efficient. European, national, or local institutions had to learn to deal with things over time, and now the support is more stable”.

Meanwhile, Daria Krivonos, a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Cultures, Centre of Excellence in Law, Identity and the European Narratives of the University of Helsinki, said international grassroots support has been waning.

“I was in Warsaw two or three months after the start of the invasion, where I had joined a group of volunteers at the station,” she told Al Jazeera.

“As early as that, it had become clear that most of those volunteers who were providing support were Ukrainian nationals, many of whom had been living in Poland prior to the latest escalation.

“At the beginning, many people came to the border with Poland to help and provide basic support to refugees. But slowly this support from international networks started to fade away. And now the situation has changed in that Ukrainian nationals are now the ones filling in the gaps left by the lack of assistance from the states, larger NGOs, and groups of international volunteers.”

Krivonos said that while a shared culture was behind European support for Ukrainians, parts of the discussion around “Ukrainian whiteness” have been “a little bit binary”.

“We can’t deny the fact that whiteness and the European-ness of Ukrainians played a huge role, but by doing this, it meant that we didn’t look closely at the history of labour migration from Ukraine, and how these labour communities are now the ones who are receiving those who are displaced. In many ways, this discussion has been rather simplistic.”

Support ‘won’t go away’

On February 24, tens of thousands of citizens took to the streets across 400 cities globally, including Western European hubs like Berlin, Warsaw and Paris, to mark the first anniversary of the war.

With the conflict set to rage on, “there are many moving parts involved in how this support [for refugees] may play out long term,” Valodskaite said.

“Firstly, it will depend on how well European governments deal with the energy costs, inflation and the overall economic situation felt in Europe as a result of the war. And then it will come down to how well the refugee issue is going to be addressed publicly. In terms of wider support, I think it may lessen or be less visible, but it won’t go away, and I do believe that European societies will continue to show strong support for people fleeing the war in Ukraine.”

Eager to see an end to the war, Rodrick said that his chapter with Sergey will not deter him from supporting a Ukrainian displaced by the war again.

“The whole experience opened my eyes to how individual people’s experiences are, and how diverse they are,” he said.

“I didn’t understand Sergey’s motivation for not wanting to be a part of the refugee asylum programmes, nor how much he had been through. The experience gave me a more nuanced picture of the experiences of those impacted by war.”