It was a day like any other; the sun shone and birds chirped. Then the sound of gunfire shattered the silence and Rabi knew that Boko Haram members had come.

It was not their first time storming Doron Baga, a settlement about 160 kilometres from Maiduguri in the northeastern part of Nigeria. This was their third attempt to take over the village since they started launching attacks in 2014, but they faced resistance from the military bases.

“Living in a small village on the outskirts of Borno at the time meant that Boko Haram attacks were always a possibility,” Rabi said, remembering the constant terror that the villagers went through after learning that other villages neighbouring them had been taken over by the terrorists.

As the sound came closer, Rabi, then pregnant in her last trimester, gathered her four children, and with her husband, Abdullahi, started fleeing into the forest surrounding their home. They joined other people and ran for three days and three nights, with Rabi’s heart pounding in her chest and her children’s hands tightly clasped in hers.

But their escape was brutally cut short when they were ambushed by the terrorists. Rabi watched in agony as the love of her life was shot dead, still holding their daughter in his arms. The bullets pierced his chest and passed through the head of the baby he was holding. “All of that happened before my eyes,” she told HumAngle, trying to hold back tears from streaming down her cheeks.

Devastated by what she witnessed, Rabi left them behind and continued running with her remaining children, passing corpses hit by the terrorists’ bullets. Along the way, she lost her pregnancy, adding to her already unbearable grief. “Clinically, I was not supposed to give birth at the time, but the unbearable trauma and the difficulties on the road forced the lifeless body of the foetus out,” she narrated.

Rabi’s story of loss resonated deeply with another elderly mother, Jummai Tukur, 60, who was in her early fifties when the disaster struck. Like Rabi, Jummai’s life was forever changed when Boko Haram members took everything she held dear, including her son, whose blood left her with haunting memories of the brutal attack.

On that fateful day, Jummai’s son and nine other young men from the village were trying to reach the safety of the Niger Republic border when they were ambushed by members of Boko Haram.

In the chaos, Jummai’s son and all of the young men were mercilessly killed. “Boko Haram stopped nine of them and shot them at once,” she remembered.

Jummai was left to struggle with the loss of her beloved son and the weight of her only surviving granddaughter’s future, who was his daughter. Jummai, like Rabi, has no family except other Internally Displaced Persons with whom she shares a camp in Hadejia, Jigawa, Northwest Nigeria.

Sa’ade Tukur, another woman in her thirties, couldn’t shake off the feeling of dread that had settled in her stomach. Her beloved sister-in-law, Fatimah, had been kidnapped, along with her two young children, by the Boko Haram terrorists after they killed her husband, Dan Muttala. They had not been seen or heard from since.

Sa’ade couldn’t help but feel a sense of anger and despair as she thought about Fatimah and her children, who were now just another statistic in the tragedy caused by the terrorist group. She couldn’t imagine the terror and fear they must have felt as they were dragged away from their loved ones. And the thought of Muttala, who had lost his life trying to protect his family, was a constant ache in her heart.

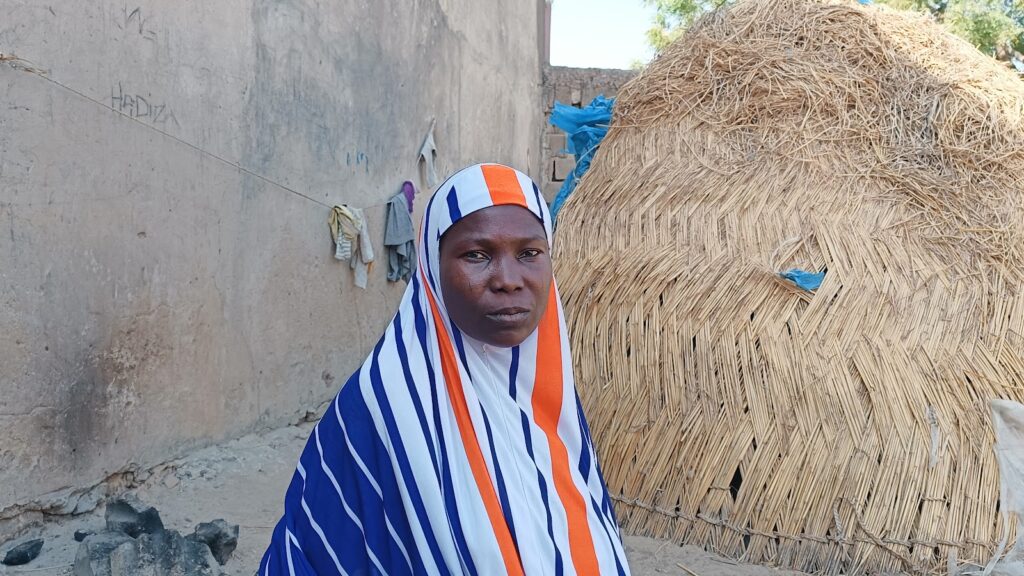

The three women, Jummai, Rabi, and Sa’ade, sat together under the sacks and canvas of their tents in an unofficial IDP camp in Hadejia. They had all fled their villages in the dead of night, leaving behind everything they had ever known to escape the brutal grip of Boko Haram. The once tight-knit community was torn apart by the crisis.

Despite their different stories, the three women were united in their grief and trauma. They found solace in each other’s company, sharing stories of their loved ones and their hopes for the future. They knew that life in the IDP camp would be difficult, but they were determined to survive and make a new life for themselves and their families.

As they sat in the dim light of their tents, the three women held on to each other, their bond of sisterhood the only thing that kept them going in the face of such unimaginable loss and hardship.

“Others, especially those with strong families and businesses, have moved to a more stable condition, but we are still here under the merciful care of God,” Jummai, the oldest of the women, said. “We get help from some people, especially A.A. Rano, but the government has abandoned us.”

During the recent flood disaster, the IDPs’ tents were washed away, their possessions were ruined, and their makeshift homes turned into mud-filled pits. They could do nothing but stand by helplessly as the floodwaters rose, engulfing everything in their path. They were given another temporary camp, and now they are planning to go back as the water dries.

“Disaster can happen anywhere, but I have never experienced something like this back at home,” Jummai said.

The long journey to Hadejia

Between 2014 and 2015, Boko Haram did a lot of damage to Doron Baga, which is an extension of Baga, a popular town known for its fishing business. Amnesty International described these attacks as the “largest and most destructive.” The terrorist group attacked the town and its neighbouring town, Baga, simultaneously, leaving behind about 2,000 people dead and over 3,700 structures damaged or totally destroyed, as satellite images indicated.

The residents fled to different places. Jummai could remember that, even though she was old and suffering from a leg injury, she was able to get to Niger Republic with the help of others. “When the Boko Haram members were approaching, a Nigerian soldier who knew me said that I should be among the first to leave because of my situation,” she recalled.

Jummai and others kept going until they were told that they had reached Niger Republic, and that was where they stopped. “You could imagine how difficult it was for an old woman like me to get there,” she said.

Others, like Rabi and Sa’ade, were able to reach Monguno and then Maiduguri in three days. But then they were told the IDP camps were full, and although they were given a place to sit, they were denied a meal ticket.

After realising that life was unbearable there, Sa’ade’s husband moved to Sokoto with her, “but life showed no mercy there either, as he was unable to make a living there”.

Around 2017, when some of the IDPs heard that the town had already been taken over by the Nigerian military, they went back. But in 2018, Boko Haram members attacked again. The residents saw relocation as the only safe choice.

Within these periods, some men among the IDPs from Doron Baga, such as Nasiru Muhammad, Muhammad Jaji, and Mallam Mamman, were all out looking for a distant and safe place with no Boko Haram presence to start a new life.

The IDPs, who had been living in a crowded camp in Maiduguri, had grown tired of being confined to the camp with no hope of a future. They longed for a life outside the camp, one where they could earn a living and provide for their families.

“We realised that life in the Maiduguri camps was not only unbearable but also came with difficulty in raising a good and moral family,” Muhammad, who is now the secretary of the IDPs in Hadejia, told HumAngle.

Muhammad said they had lost everything when Boko Haram attacked their village – their homes, their possessions, and their livelihoods. They were trapped in a cycle of survival, living day to day with little hope for a better future. But then, a glimmer of hope appeared when they were approached by a group of locals from Hadejia who offered them a chance to start over.

The locals had connections with them in the fishing industry, and they offered to help the IDPs set up as fish sellers in Hadejia. It was a difficult decision to make, leaving the relative safety of the camp in Maiduguri for the unknown in Hadejia, Muhammad said. But the IDPs knew that they couldn’t go on living as they were, and they knew that they had to take a chance.

With nothing but a dream and the clothes on their backs, Muhammad and other fishermen decided to set out on the long journey to Hadejia. They were filled with a sense of hope and determination as they thought of the new life that awaited them. They were the first people to be there.

When they arrived, they were welcomed by the locals, who provided them with makeshift camps to live in. It was a far cry from the homes they had lost in Doron Baga, but it was a start. That opened the door for others to join. Hundreds followed.

The IDPs soon found out that starting a new life in Hadejia was not going to be easy. They faced many challenges, especially with locals who feared that Boko Haram members could use that opportunity to attack Hadejia. Then there were those who feared mixing with them.

“To remove that doubt and to make it clear that we are here for peace, we formed a Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) that monitored whoever came from Borno to here,” Mamman, who is a member of the task force, told HumAngle. “We were able to catch two Boko Haram members, and since then they haven’t come here again.”

The IDPs banded together, pooling their resources and sharing their knowledge. They worked hard to establish themselves as fish sellers, and slowly, they began to see the fruits of their labour.

“From those who import fish from Niger Republic to those doing menial jobs in the market, all of those who came here with nothing have gotten something,” said Alhaji Haruna Shu’aibu, chairman of the Hadejia fish market.

Shu’aibu said that the brotherhood between the locals and the IDPs has reached the level of intermarriage. “As you can see, I just came back from a wedding ceremony between the families of IDPs and the locals,” he said.

So far, the IDPs were proud of what they had achieved, and they were grateful to the locals who had helped them along the way. They knew that they would never be able to fully forget what they had lost, but they also knew that they had the strength to rebuild their lives and create a new home in Hadejia.

Something missing

As they sat in their tents, the IDPs couldn’t help but feel a sense of homesickness. They knew that they would never truly be home until they were able to return to Doron Baga. But, according to them, it is not yet time.

The IDPs in Hadejia have been in contact with some of their family members, but the distance and the trauma of the past have made it hard for them to reconnect. They missed the sense of belonging, the feeling of being surrounded by people who knew and loved them.

“I tried going back, and I even went there, but I was told that Boko Haram still posed a threat to the people, so I came back,” Jummai said.

She has no one in Hadejia and because her son was killed, she doesn’t have natural support within the IDP community in Hadejia. Still, others support her, including her neighbours.

In 2018, the terrorists returned and attacked Doron Baga. They were able to seize control of the town from the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) until 2019 when the military took over from them.

In 2022, MNJTF reported that it had returned 60,000 refugees and IDPs to their homes in Baga, Doron Baga, Bindiram, and Banki, among other towns and villages, in what the International Crisis Group called an “aggressive programme of relocating” that was “too fast”.

The IDPs in Hadejia said they have no plan of returning until they see the presence of perfect and lasting peace.

“No one among them is not missing home,” observed Jaji, but it’s better to be in a safer place than to return to a place where there is no guarantee of peace.

“We’ve had firsthand experiences with Boko Haram violence; it is hard to forget, but we are still building here, and with enough time we will integrate and make Hadejia our new home,” Jaji said.

Sa’ade yearns to go back, believing her hometown will provide stability.

“Living here is unstable. We don’t know when the owner of this place will ask for it. We were returned here after the flooding, and even that camp is owned by someone,” she said.

Rabi has lost everything, including her home and her husband. She is determined to go wherever her daughter, who is now married to another IDP, will take her. She is currently supporting herself by doing menial jobs for locals, such as “surfe” (manual grinding) and house chores.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.